Visiting the Whitechapel Gallery after lockdown was the first time, to my knowledge, that I had my temperature read in public. I can tell you that I saw Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium on Sunday, July 26 at 4:30, because I had to book in advance and I still have the confirmation email. Having opened on February 6 with an original closing date of May 10, the show was among those caught in lockdown limbo. Upon the gallery’s re-opening, Radical Figures was extended to August 31. Just inside the doorway, as gallery staff wore Perspex visors and an iPad-like device scanned my face for signs of fever, I became intensely aware of my own body. I felt plastic, as if I were turning inside out, while at the same time the borders between myself and others were reinforced by acrylic dividers and two-meter distances.

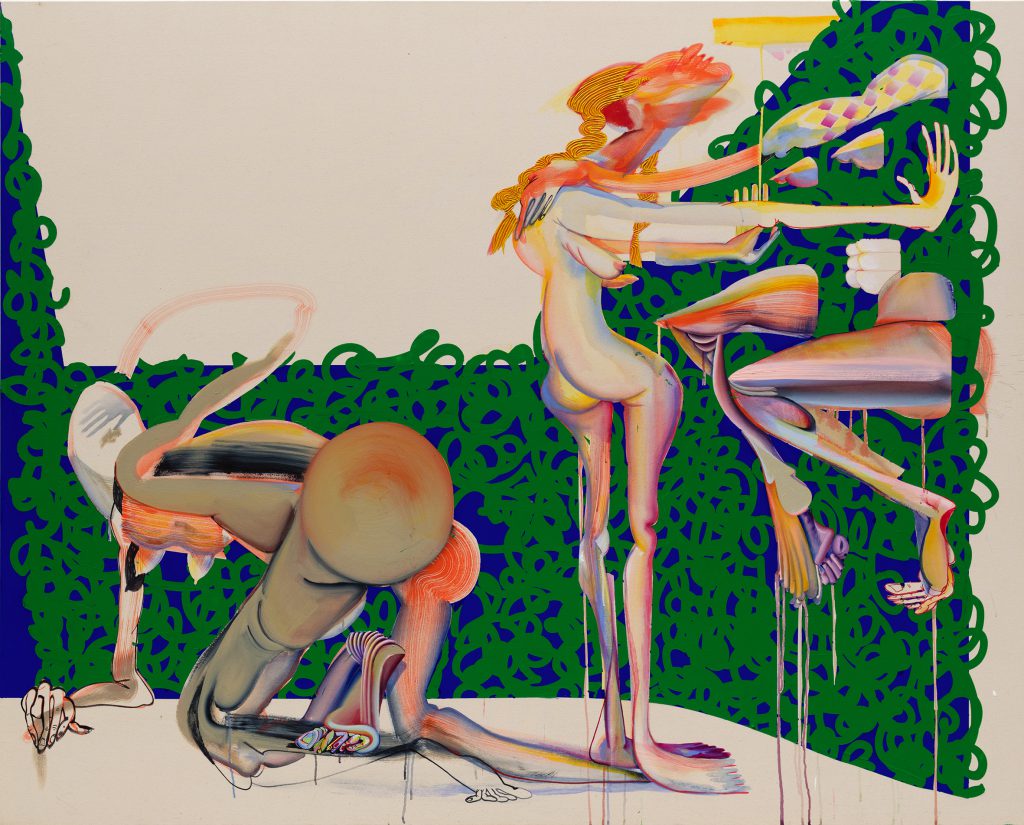

These check-in procedures, though important and absolutely necessary, made for an unsettling introduction to Radical Figures, which featured works by young artists like Christina Quarles, Michael Armitage, and Tschabalala Self, alongside those recognized as indispensable to contemporary figurative painting, namely Nicole Eisenman, Dana Schutz, and Cecily Brown. The anxious and awkward bodies on view seemed to respond to contemporary questions of identity and representation. Are Quarles’s figures dripping and clay-like because identity is too fluid to be captured in categorical definitions? Or are they so cut through by attempts to impose these definitions that they melt like wax under the gaze of others? I can’t claim to know these feelings from experience. But in a strange way, the Covid-safe protocols that allowed me to enter the museum in the first place were like preludes to the exhibition itself, a performance of bodily management. I felt like a piece of clay in a Quarles painting, unsure of its boundaries.

Gradually, things like wearing a mask, scanning QR codes to download digital press releases, and scheduling gallery appointments via email, Eventbrite, or the newly launched ARTSVP system, became second nature. Getting used to the pre-booking process was a problem, at first, because I don’t know if I’ll want to visit an exhibition in Shoreditch at 2:15 next Tuesday. But even if this is difficult for me, appointment scheduling could be helpful for gallerists in repairing the interruption to intimate, in-person contact with clients caused by the pandemic.

Niru Ratnam—whose gallery improbably opened during the pandemic—told me that his experience with visitors has been more personable, with people tending to linger longer and converse instead of popping in and out. Maybe this is because people are making appointments and setting time out of their day to see art; or maybe this is because people are happy to see art in person again. Ratnam was showing work by Matthew Krishanu in an exhibition titled Picture Plane (September 16–October 24), which featured serene paintings punctuated by explicit references to colonialism and missionary work. Small churches sit on high horizon lines, the fields and bodies of water beneath them dissolving into fluid abstractions that recall Richard Diebenkorn’s work. The most striking painting in the show is Mission School, in which seated students study a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Famous for its one-point perspective, the reproduction interrupts the predominate flatness of Krishanu’s painting, signaling the incursion of Western structures of seeing and thinking so closely tied to legacies of imperial power.

After a summer of online viewing rooms—which seem to be here to stay at least for the time being—it was invigorating to see art in person again. To see paintings come out from behind a MacBook screen, and to be able to consider not only color and composition, but texture and material treatment as well, were things I had not realized I was missing. Sid Motion, who showed the artist Max Wade as part of her eponymous gallery’s participation in Platform: London, presented his paintings in person over the fall. She mentioned to me that interest in the artist that was sparked online with Platform had carried over into the exhibition Max Wade: Sowing the Soil with Salt (September 10–October 24)—which can only be a good thing. The work begs to be seen in the flesh.

Wade’s large-scale canvases are caked in layers of paint, the occasional hand and fingerprints visible where he has clawed and smeared the pigment. Using rollicking and raucous color, Wade is clearly unafraid of creating jarring and unconventional chromatic clashes in a manner indebted to painters like Amy Sillman. And it seems he has a kindred spirit in Rachel Jones, whose own heavily worked oil pastel compositions dial up the saturation and contrast in a body of work that seethes in color and intensity. Smartly paired with the wooden, ovoid sculptures of Nicolas Pope in a brief two-person show at The Sunday Painter (September 14–26), Jones’s work is captivating. Moments of calm pastel pinks, blues, and earthen tones are overwhelmed by cadmium red. The sense of unease is sharpened when the organic shapes—which first reminded me of Friedel Dzubas’s monumental processions of irregular rectangles—slowly take form as rows of clenched teeth.

Clenching teeth is an appropriate physiological response to the first half of 2020. The low-grade atmospheric anxiety of lockdown was strange in texture. Collectively, we were in a new situation that required us to stay home and not see each other, even if loved ones elsewhere were sick with Covid. We were all having restless nights and bad dreams. I looked forward to when the apartment got dirty so that I could clean it. Even so, there was a feeling that in spite of the extreme isolation, we had never been more thoroughly in the world. In our rooms, we were still receiving transmissions from a world outside coming to terms with the social and political inequalities laid bare by the pandemic. Impassioned conversations and protests of historical urgency somehow coexisted alongside the embodied experience of lockdown as a yawning vacuum, exacerbating the feeling of what Eula Biss—borrowing from the anthropologist Emily Martin—describes in her newly relevant book On Immunity (Graywolf Press, 2014) as “empowered powerlessness.” Understanding one’s place as part of an ecology, complicit in its machinations though incapable of challenging its direction, is a condition, Biss states plainly, endemic to American democracy.

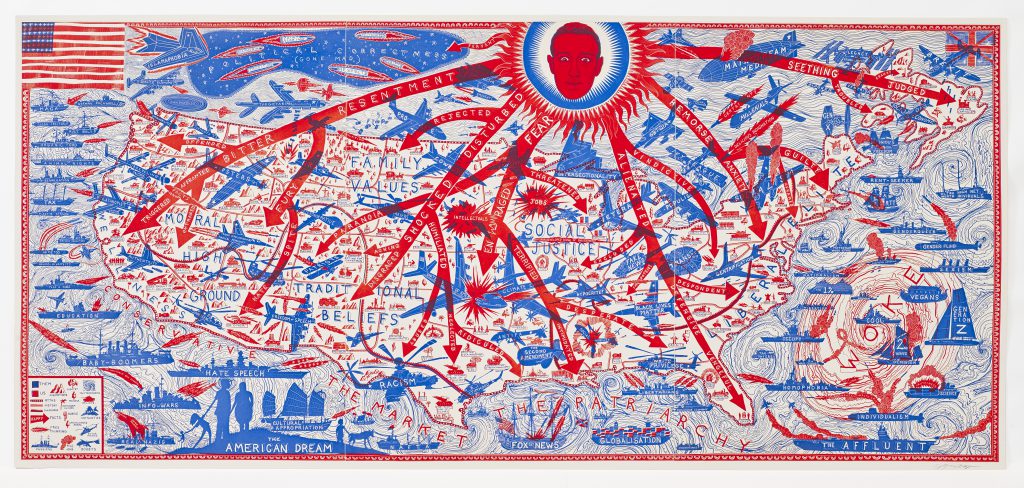

The British artist Grayson Perry’s new show at Victoria Miro takes the temperature of the United States at its most volatile. Titled The MOST Specialest Relationship (September 15–October 31), the exhibition is refreshing in that Perry skewers everyone across the political spectrum, even if the form of his critique can at times be heavy handed. On one ceramic vessel emblazoned with guns and social media icons, the stars of an American flag are replaced with the Apple logo, its stripes repeated rows of Playboy bunny heads. None of this is exactly news to me, but then again as an American abroad, maybe I am not the target audience. The stand-out work in the exhibition is The American Dream (2020), a print of an imaginary map of the US littered with buzzwords from both the political left and the right, while the head of Mark Zuckerberg presides over the scene as both savior and tormentor. Putting together the work in my head, my internal monologue sounded like a weather report of conflict: Just over the East Coast of Liberal Elite we’re seeing some bomb showers of gentrification, while White Privilege hovers over the Florida Panhandle. Meanwhile, if we look over to the Gulf of Patriarchy, the ships Fox News and Globalization are experiencing some choppy waters while Hurricane Woke is forming in the Atlantic. Over the coming days, we’ll begin to see Vegans, Second Wave Feminism, and Generation Z pulled further into its vortex, with serious problems for the 1%. Breaking news just coming in over Oklahoma now, we’ll take you there live, where two planes have just collided. I can confirm here, now, that the planes have been identified as Climate Change and the United States of America. I was laughing through clenched teeth.

Viewing the print with my own private monologue was overwhelming. Transcribing it now reminds me of the comfort we often look for in the media as we search for clarity and answers in an impossibly murky situation. Looking at the news during the pandemic was like watching Omar Fast’s tremendous film CNN Concatenated (2002), which resonated deeply in the fearful post 9/11 climate. From mashed together snippets of news anchors flows a narrative of our unconscious motivations for media consumption. “Look, I know that you are scared. I know what you’re afraid of,” Fast’s hydra of Wolf Blitzer, Judy Woodruff, and Christiane Amanpour report. In the midst of lockdown—punctuated by my own endless doom-scrolling in anticipation of the daily Covid afternoon press briefing—I felt like I needed a lockdown away from lockdown.

It was over the summer that I heard of Dungeness for the first time, a remote headland on the coast of Kent. Its desolate lunar landscape appears on the opposite end of the picturesque spectrum from “English countryside.” I would imagine that it’s the closest thing to a desert England has. I didn’t go. But trawling Google Images, I found photo after enchanting photo of flattened, rock-strewn fields stretching to the horizon, a beached boat, a railway in disrepair, and a nuclear power plant—images oozing with romantic entropy, representations of how lockdown felt but without the anxious static. It’s as if Dungeness were a site that had accepted its fate, and was at peace with it.

Within this inhospitable region, the poet, activist, and visual artist Derek Jarman took on the seemingly impossible task of planting a garden, which is the subject of My Garden’s Boundaries are the Horizon at the Garden Museum in Lambeth (July 4–December 13). The show features a recreation of Prospect Cottage, where Jarman began living around the time of his HIV diagnosis in the mid-1980s. Inside are the artist’s gardening tools, gardening books, and journals, as well as several paintings, assemblages, and two of his films. Though the exhibition had a timed entry, the small house forced visitors into close quarters, stopping and starting to keep as much distance as possible. The residual effects of lockdown, and the current necessity of maintaining distance, manifested once again in Jarman’s own terminal island—terminal, both in reference to Prospect Cottage’s seeming location at the edge of the Earth, as well as to the virus that would claim the artist’s life. One of Jarman’s highly textured and expressive paintings is emblazoned with the words “AIDS Memoir. Et in Arcadia Ego. I was here. Prospect Cottage.” The Latin expression is a reference to the Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin’s artwork of the same name. One interpretation of Poussin’s famous painting is that the words “I am also in Arcadia” are death’s own.

Traditional English landscape gardens are themselves sites of time, peppered with architectural follies and ruins that spark meditation on life’s ephemerality and ultimate finitude. The same can be said of Jarman’s, even if in an entirely different form. Alongside Dungeness’s native plants, Jarman attempted to grow non-native species, with failures and successes, while erecting sculptures of found objects and driftwood scavenged during his walks. There is something powerful about a place named “Prospect” housed in a site whose name sounds as inhospitable as “dungeon.” It hints at the possibility of a future where one is unlikely to be found. Expressions of hope and life in a place that seems devoid of both become important lessons for life after lockdown.

Text © Nathan Jones 2020