Over the past several weeks Londoners have been living in a time warp. On Friday, March 12, I visited White Cube Bermondsey where, as my phone convulsed with push notifications and emails of museum closures in the United States, a gloved gallery attendant stood by the entrance to open the door for me. As each country waits in anticipation of their respective peaks in the COVID-19 crisis, Britain does as well, with Boris Johnson urging the importance of flattening the curve to ease the burden on the strapped National Health Service. But while waiting for the spike, trends in other nations offer a picture of what the future might have in store.

So it follows that the week of March 15 began with a trickle of museum and gallery closures followed by a flood. Among the exhibitions closed or postponed is the National Gallery’s much-anticipated show of Artemisia Gentileschi. These decisions were made at the discretion of the institutions as the government sowed confusion by recommending social distancing while displaying a reluctance to impose restrictions on business operations or public life. In a March 17 statement published on its website, the Museums Association bemoaned the lack of clarity, writing, “Governments in all four nations should provide clear advice on whether institutions have to close; on what constitutes essential travel for workers and the public; and further information for staff and the public on social distancing.” Since this time, however, life in London has ground to a halt. On March 23, Johnson ordered the British public to stay indoors, with the exception of essential errands for food and medicine as well as one form of outdoor exercise per day. Police have been given the authority to disperse crowds of larger than two and to issue fines.

Under conditions of lockdown, art institutions as well as their workers and freelancers face existential threats. In response to the crisis, the Arts Council of England announced on March 24 that it will free £160 million in funding for cultural organizations and workers, a disbursement that the Council says nearly depletes its reserves. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak offered further support to freelancers on the evening of March 26 by announcing a scheme that will see the government supplement 80% freelancers’ average monthly earnings capped at £2,500 per month. This could, however, come at a price for freelancers further down the line. Given that the relief is comparable to that extended on March 20 to employees, Sunak hinted during his announcement that both employees and freelancers should contribute equally to taxes.

With London now brought to a complete standstill, the crowds and workers normally populating its cultural institutions have moved online. The Art Newspaper shared Seb’s [Art List], which has compiled an ongoing list of gallery closures and resources, and created a Slack channel for members of the art community affected by the pandemic. Seb’s [Art List] also links to Marguerite, a group dedicated to supporting women in the arts that is currently allowing freelancers to post their credentials for review by possible employers. Meanwhile the British Museum has reported an increase in traffic on its website, while those in quarantine are enjoying the popularity of Instagram accounts like @tussenkunstenquarantaine and the hashtag #museumfromhome. At a moment when the original tools of social distancing—Instagram, et al.—seemed to actually approach their envisioned purpose of providing a platform for community, I hurried to the galleries for one last walk-through as the pause button ominously loomed. What follows is a collection of several stand-out exhibitions originally scheduled through March and into April or May, but are now in our shared limbo.

Ishbel Myerscough: Grief, Longing, and Love

Flowers

March 4–April 11, 2020

Temporarily closed

Visiting Ishbel Myerscough’s latest exhibition is like taking inventory of a now-absent person’s artifacts and finding a photo album. Filled with people you do not recognize, their gestures and expressions are so redolent of an inner life that you cannot help but feel a human connection. Myerscough’s career as a painter has been defined by training her sympathetic gaze on family members and friends, her empathy for the sitters recorded in her replication of each blemish, freckle, and stray hair: the peach fuzz rimming the ear of the young face in Herb (2019); short black whiskers the razor cut; thin wispy whiskers the razor missed; open pores; sprouting unibrow. The portrait continually opens, as do the subjects. Across the gallery Herb sits, a year prior, in Herb with Black Eye (2018).

Ishbel Myerscough, Fraser Asleep, 2018. Oil on board, 5 1/8 x 7 1/8 in. (13 x 18 cm).

Photo Nathan Jones.

In an exhibition so deeply personal, there are a few instances where catharsis for the artist—two paintings of dead birds; a series of self-portraits of Myerscough in tears—might not connect as powerfully with audiences. The most successful pieces leave the pathos roiling just below the surface. The two postcard-sized portraits of Myerscough’s children asleep are haunting, capturing the concern, trepidation, and wonder only a parent could have.

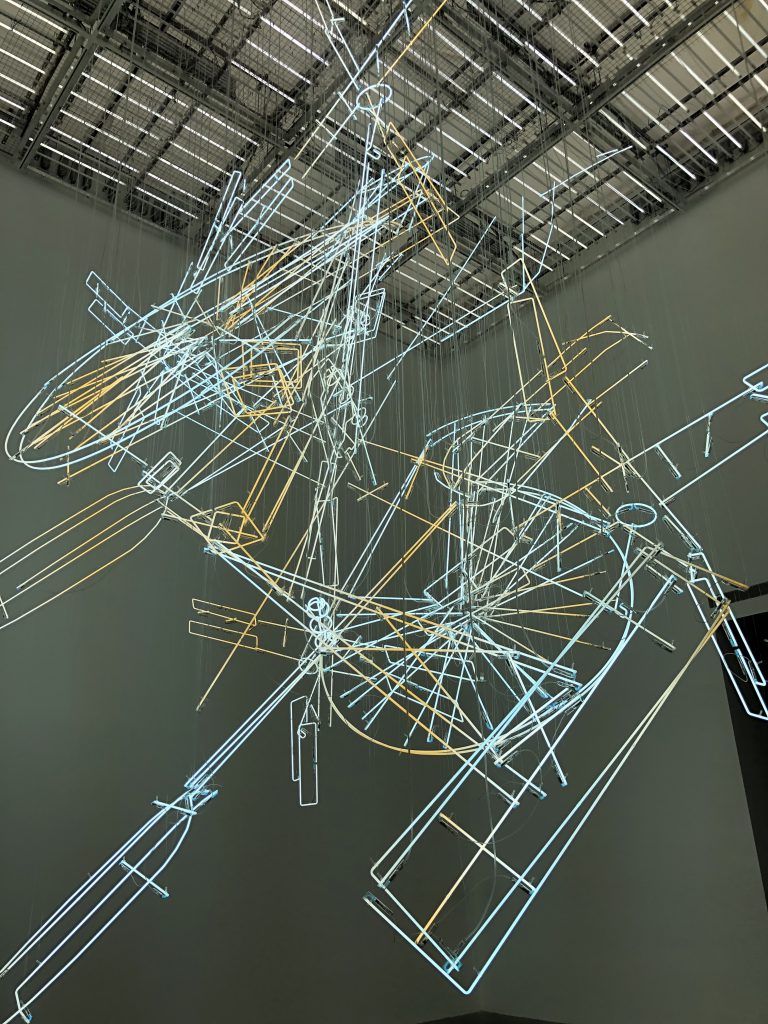

(730 x 707 x 519 cm), at White Cube. Photo Nathan Jones.

Cerith Wyn Evans: No realm of thought . . . No field of vision

White Cube Bermondsey

February 7–April 19, 2020

Temporarily closed

The most recent exhibition by Welsh artist Cerith Wyn Evans features sculptures composed of materials typically invisible, namely glass and the compressed gas of neon lights. But these elements bear a heavy conceptual load as Evans plucks images from history and translates them into suspended neon-light sculptures or transparent glass, literal floating signifiers awaiting new meaning. Whether distilling art historical references like Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel into vectors of neon light ( . . . take Apprentice in the Sun I-IV, 2020), or using glass as a resonate material to amplify sound (Pli S=E=L=O=N Pli, 2020), Evans’s work gains its potency through the gaps that translation between media open up.

at White Cube. Photo Nathan Jones.

At a moment when life seems predetermined, when past behavior becomes data used to ruthlessly capitalize on future behavior, Evans’s work is a powerful disruption. With all of his expansive thinking perhaps Evans’s most crucial point of reference is Marcel Proust, whose text describing the path of water prescribed by a fountain is translated here into a curtain of Japanese characters (F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N, 2020). It is an image of Proust’s description, but like water, the image is mutable and may take any form. A doorway allows the viewer to pass through this representation, a fleeting encounter with the life of an image.

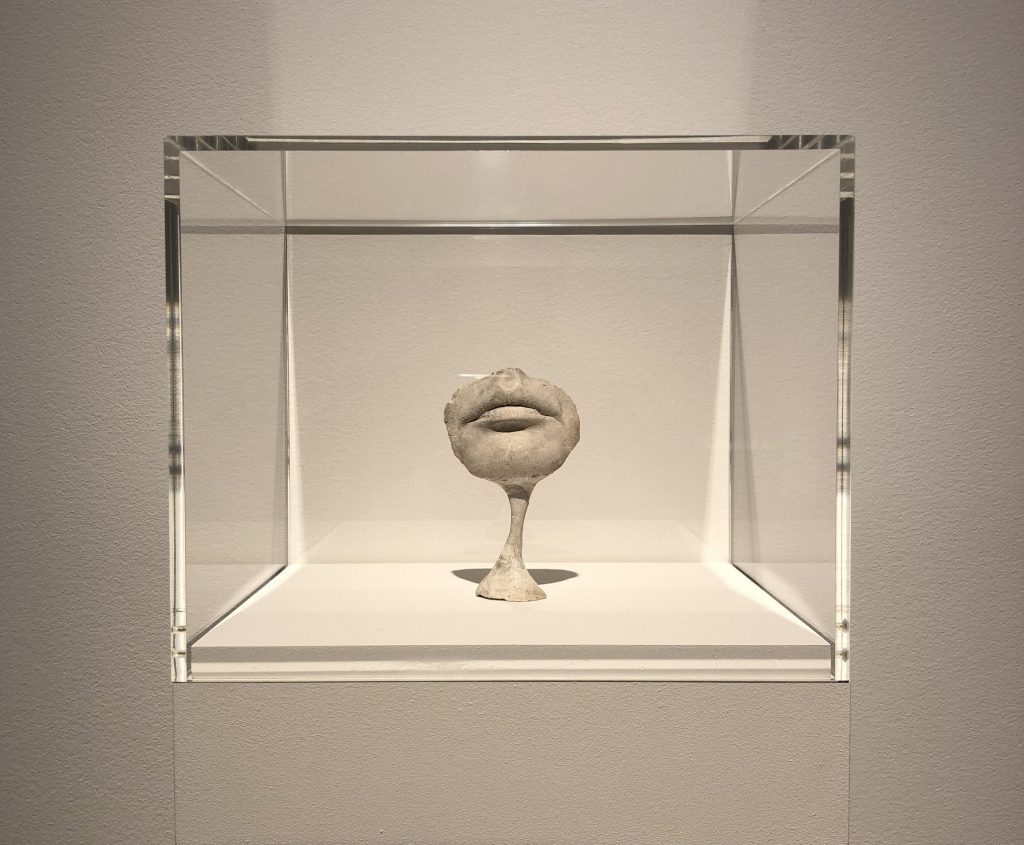

To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962–1972

Hauser + Wirth

February 7–May 2, 2020

Temporarily closed

Alina Szapocznikow’s exhibition at Hauser + Wirth is a quiet collection of human traces recorded in cast body parts, flayed skin, and abject viscera. A version of To Exalt the Ephemeral was recently presented at this gallery’s New York branch, and focuses on those years in which the Polish artist—had she lived in New York—would have been a central figure in the development of “eccentric abstraction.” For Szapocznikow, a survivor of both the Holocaust and tuberculosis before succumbing in 1973 to breast cancer at age 46, personal history manifests as an aggregate of absences written on the body. Photographs are encased in folds of skin (Pamiątka I [Souvenir I], 1971), while a flattened cast of her son resembles a shattered and disproportionate Greek sculpture (Herbier bleu I [Blue Herbarium I), 1972).

Despite the somber mood, there are surprising moments of brevity. In addition to Szapocznikow’s lamps composed of phalluses and mouths (Sculpture-lampe [Sculpture-Lamp], 1970), the artist takes on the weighty topic of absence in a humorous suite of black-and-white photographs (Fotorzeźby [Photosculptures], 1971/2007). Formed in the void of the mouth, heavily chewed pieces of gum pose like sentient beings and smartly distill Szapocznikow’s exploration of indexicality to its simplest form.

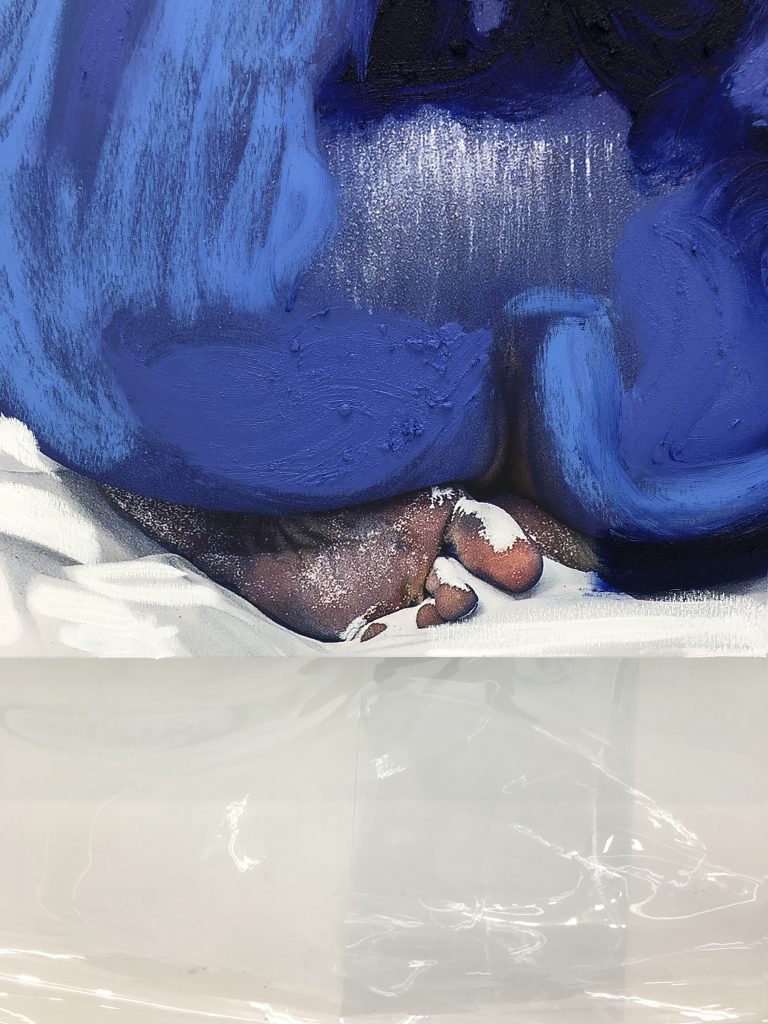

Donna Huanca, Wet Slit

Simon Lee

February 28–April 18, 2020

Temporarily closed

In past exhibitions, Donna Huanca has staged vibrant settings comprising painting, sculpture, and nude performers painted to match their environment. While Huanca’s debut at Simon Lee lacks the crucial presence of these models and includes no scheduled performances, the dissonance between the self-consciously astringent environment and her fluent canvases underscores the artist’s reconsideration of the act of painting. Installed against sheer plastic curtains that shroud the walls of the first-floor gallery—a toxic smell of cleanliness wafting off the clear polythene—Huanca’s paintings do not disclose or seek to represent; rather, they obscure and cover. Like paint coating the hulls of cargo ships, Huanca’s pigment-covered models—all women of different races and gender identities—are shielded from the elements, from the projections of prying eyes. For her paintings in Wet Slit, Huanca enlarges photographs of her painted models during past performances as digital prints before covering the images in thick, fluid brushstrokes. The models therefore receive a second coat, one more layer of obfuscation, the occasional foot and face surfacing from water-like cascades of paint.

Moving to the downstairs gallery—with its deep blue walls, matching carpet, incense, low light, and large mural—is a transition from the antiseptic first floor to a more serene and comforting environment. It feels cave-like, as if entering the basement gallery is the equivalent of passing through Huanca’s waterfalls of paint and entering a hidden grotto. This must be the private space that the performers, hidden in plain sight by paint, have carved out for themselves.

Text © Nathan Jones 2020

Very good yeah, they’re things in life enriched my knowledge i believe that anything is possible.

Your website is amazing congratulations.

This is quality work regarding the topic! I guess I’ll have to bookmark this page. See my website YR4 for content about Airport Transfer and I hope it gets your seal of approval, too!