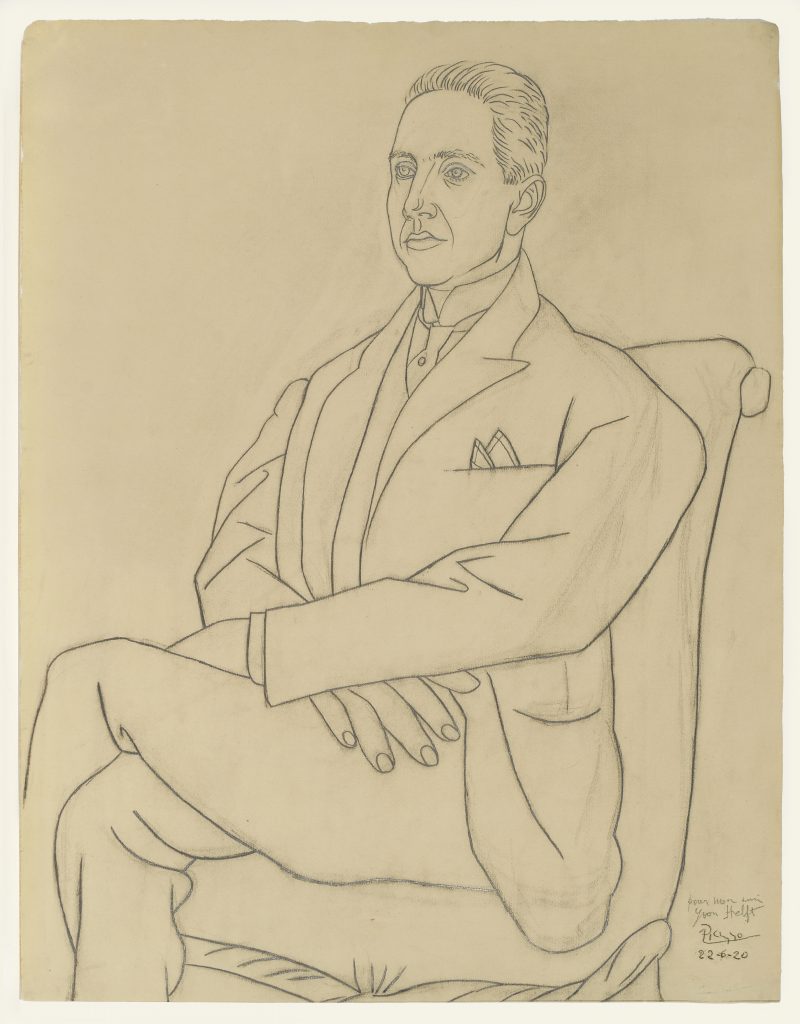

June 22, 1920

Pencil on paper

24 x 18 3/4 inches

Photo Courtesy Jeffrey H. Loria & Co., Inc.

1. Pablo Picasso at Jeffrey H. Loria & Co.

Each year The Art Show, hosted by the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA), affords the rare opportunity to see what treasures some of the country’s preeminent private dealers and appointment-only galleries have sequestered behind those mysterious closed doors. This year, Jeffrey H. Loria & Co., based in New York City and Southampton, dazzles art-fair goers with a stunning display devoted to Picasso. On view are some rarely exhibited paintings and works on paper from the 1920s to the 1970s—none more arresting than the maestro’s large 1920 drawing of the art dealer, Portrait d’Yvon Helft. Less well known than Picasso’s portrait drawings of composers Eric Satie and Igor Stravinsky from the same period, the sinuous lines and deft composition of Yvon Helft lend the figure a monumental quality, as well as a palpable expressivity. The late, great art historian John Richardson said of these portraits in his biography A Life of Picasso (1990), that the artist “adopted a style that has a van Gogh-like intensity and rigor.” The intensity in Portrait of d’Yvon Helft centers on the outrageously exaggerated fingers of the sitter’s right hand.

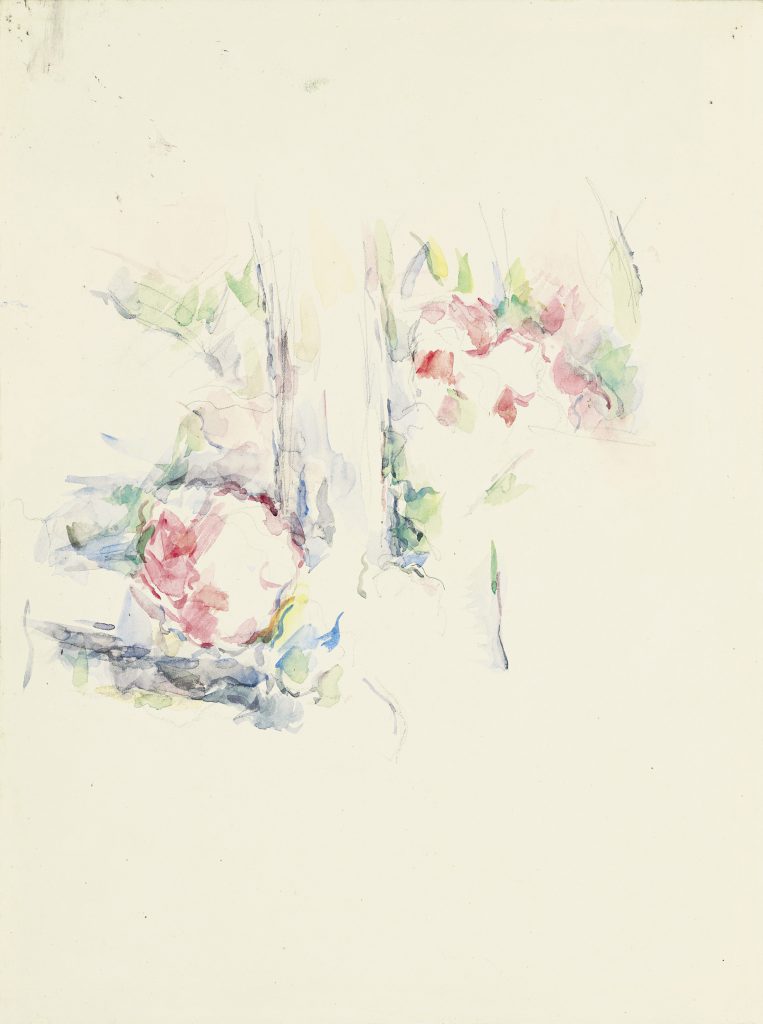

watercolor, 16 5/8 by 12 1/2 inches

Photo Courtesy Jill Newhouse Gallery.

2. “The Roots of Modern Landscape 1820-2020” at Jill Newhouse Gallery

Historical and thematic surveys are often among the most rewarding viewing experiences at The Art Show. “The Roots of Modern Landscape 1820-2020” is one of them, and it explores the development of landscape painting via small but poignant examples by artists ranging from Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot to a Matthew Barney. The relationship between Victor Hugo’s vision of a landscape and Cecily Brown’s may be discussed here, as well as the enduring legacy of Paul Cézanne, represented in the show by two radiant watercolors. With delicate touches of brilliant color, his spare but luminous Tree Trunks and Flowers (ca. 1900) seems fresh and vibrant. To be included in an upcoming Cézanne watercolors exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, the work suggests, with Zen-like economy, an epic story of being immersed in nature.

Zanele Muholi. Kusile III, 2002 Cartwright, Cape Town, 2019.

Gelatin silver print.

© Zanele Muholi.

Courtesy the artist; Yancey Richardson, New York; and Stevenson, Cape Town / Johannesburg

3. Zaneli Muholi at Yancey Richardson

South African artist and activist Zaneli Muholi stole the Arsenale exhibition at last year’s Venice Biennale with her mural-size black-and-white photographs that punctuated the cavernous space with a high-spirited bravado. While containing one large example, The Art Show exhibition features recent smaller-scale photographic works that afford a more intimate and perhaps clearer view of the artist’s endeavor. With a powerful graphic quality, this series of striking self-portraits show the artist wearing various accruements associated with places in Africa she has visited recently. They make powerful statements regarding race and gender discrimination, and comment on the socio-political situation in Africa. A work such as Kusile III, 2002 Cartwright, Cape Town, 2019, in which the artist covers herself in African currency, alludes not only to the history of the slave trade but to systemic gender inequality in today’s global economy.

Installation view, showing

Jitterbug II (ca. 1941), above, and Training for War (1941-42), screenprint on paper, below.

Photo David Ebony

4. William H. Johnson at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

South Carolina-born William H. Johnson (1901–1970) studied in New York and traveled and painted extensively in Europe for some years before settling back in the United States in 1938. This mini-retrospective contains paintings that show his technical mastery early on as he absorbed the lessons of artists such as Picasso and Braque to develop his own quasi-Cubist style in depictions of the French countryside. Upon returning to New York, he began teaching in Harlem; in his work, he adopted a folksy, “primitive” style, as he termed it, in which to better explore and express the African American experience. On view here are collage-like compositions such as Jitterbugs II (ca. 1941), and Training for War (ca. 1941–42). The striated, herringbone design on the walls of the booth added to the pulsating, rhythmical quality of the compositions. Johnson achieved some success with these works, but his career was tragically cut short; after being diagnosed with mental illness in 1947, he spent the rest of his life in a Long Island hospital.

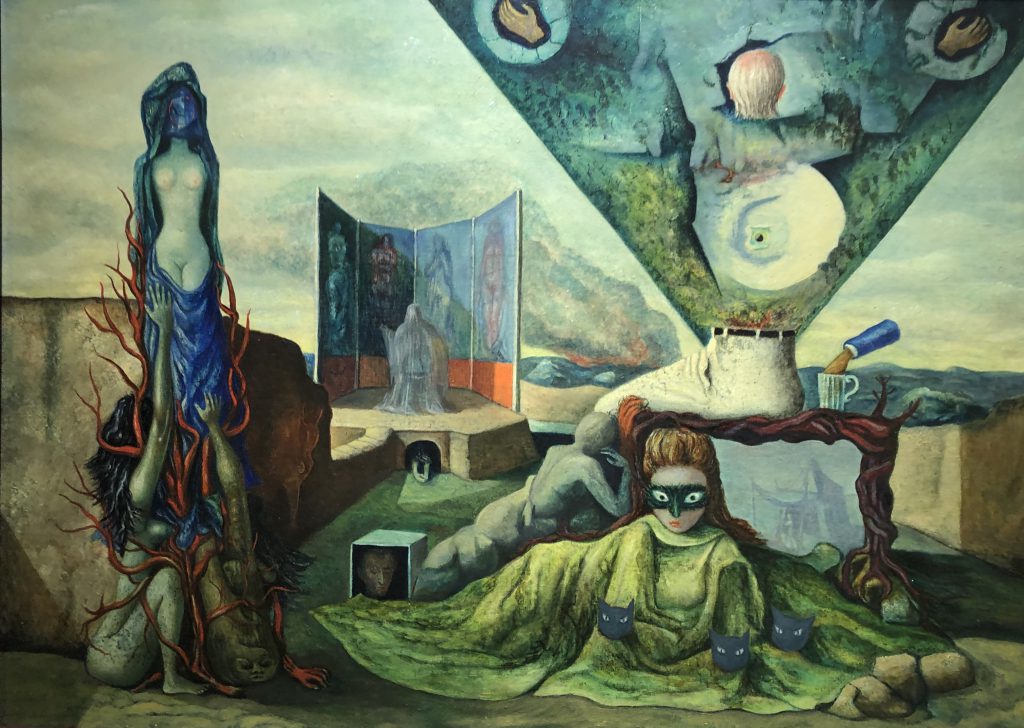

oil on canvas

Photo David Ebony

5. Gunther Gerzso at Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art

A Mexican artist of German-Hungarian heritage, Gunther Gerzso, had a successful career as a set designer for stage productions and major films by directors including John Ford and Luis Buñuel. Through the latter, he got to know many of the expatriate European Surrealist artists and writers, including Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, who had settled in Mexico City as war refugees. The influence of these artists may be felt in the early works by Gerzso on view in this concise survey, such as The Days of Gabino Barreda Street (1944). Here, the artist presents a mashup of fantastical set pieces for films. The characters portrayed here allude to both actor and artist friends. Later, Gerszo developed a more abstract visual vocabulary with delicately nuanced layered planes of color referencing Mexican landscape elements and pre-Columbian architecture. These works are also well represented here.

Color pencil and graphite on brown paper with hand painted camouflage mat

29 by 26 inches

Photo Courtesy Venus Over Manhattan, New York

6. “Remembering Phyllis Kind” at Venus Over Manhattan

This presentation pays tribute to dealer Phyllis Kind (1933–2018), whose eponymous galleries in Chicago and New York introduced art audiences to experimental figuration in painting and sculpture. She represented artists like Roger Brown and Robert Colescott, whose works are on view here. In her galleries, visitors entered the weird and wacky world of the Chicago imagists, including artists Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Karl Wirsum, and others. Especially memorable in this outstanding booth is Jim Nutt’s work on an irregularly shaped paper sheet, with a hand-painted mat, I’ll be back in minute (1973). This image of a freakishly—and comically—distorted male and female couple, merges the refined drawing style of the Old Masters with the acerbic ire of Vietnam-era counterculture.

chicken, turkey, rabbit and fish bones, 16 1/8 inches high.

© 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid.

Photo by Rafael Doniz

Courtesy Gallery Wendi Norris Gallery, San Francisco.

7. Remedios Varo at Gallery Wendi Norris

This San Francisco gallery brought to New York some rarely shown works by Surrealists Leonora Carrington (British-Mexican, 1917–2011) and Remedios Varo (Spanish-Mexican, 1908–1963), who had fled war-torn Europe and settled in Mexico City. The most striking piece on view, Remedios Varo’s strange and wildly beautiful Homo Rodans (1959), her only sculpture, is made of chicken, turkey, rabbit, and fish bones she gathered after a friend’s dinner party. Displayed in a vitrine, it resembles a natural science museum specimen. It also recalls one of the elaborate chicken bone sculptures by Milwaukee outsider artist Eugene von Bruenchenhein. Varo created a mythical context for the object as a skeleton of a hybrid creature: half-human, half-machine. In the guise of a fictional German anthropologist author, she produced a fantastical, illustrated manuscript describing the evolution of the creature, which is also on display in a nearby vitrine.

collage on panel, 85 1/2 x 73 1/2 inches.

Courtesy Pace Prints.

8. Nina Chanel Abney at Pace Prints

The searing colors and crisp design of Nina Chanel Abney’s recent large-scale collages, such as She was a Real Trouper— Acts of Service (2020), would be appealing on any level. The highly styled and vibrant graphic effects of the imagery correspond neatly at The Art Show with the historical works by William H. Johnson presented by Michael Rosenfeld. In addition, Abney’s poignant themes of racial inequality and the meaning of patriotism in the midst of a resurgence of white nationalism, makes this show, “Who’s Got Team Spirit,” one of the strongest presentations at this year’s fair.

Judy Fox. Snake Tree, 2015–19.

Terra cotta, casein.

Courtesy Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New York

9. Judy Fox at Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Some of the figurative ceramic sculptures here by New York artist Judy Fox were inspired by biblical scenes from Genesis, and especially by Lucas Cranach’s visionary paintings of the same biblical text from the 1500s. Fox’s 3D interpretation is of a phantasmagoric Garden of Eden that might have been. Surreal, plant-animal hybrids appear as spiny sea urchins with breasts, or Venus flytraps with legs. Made of painted terracotta, each of the sculptures is a technical tour de force. The largest work, Snake Tree (2015–2019), looming about seven feet tall, resembles Cranach’s tree in Eden, but this would-be apple tree has apparently morphed into a menacing, coiling serpent.

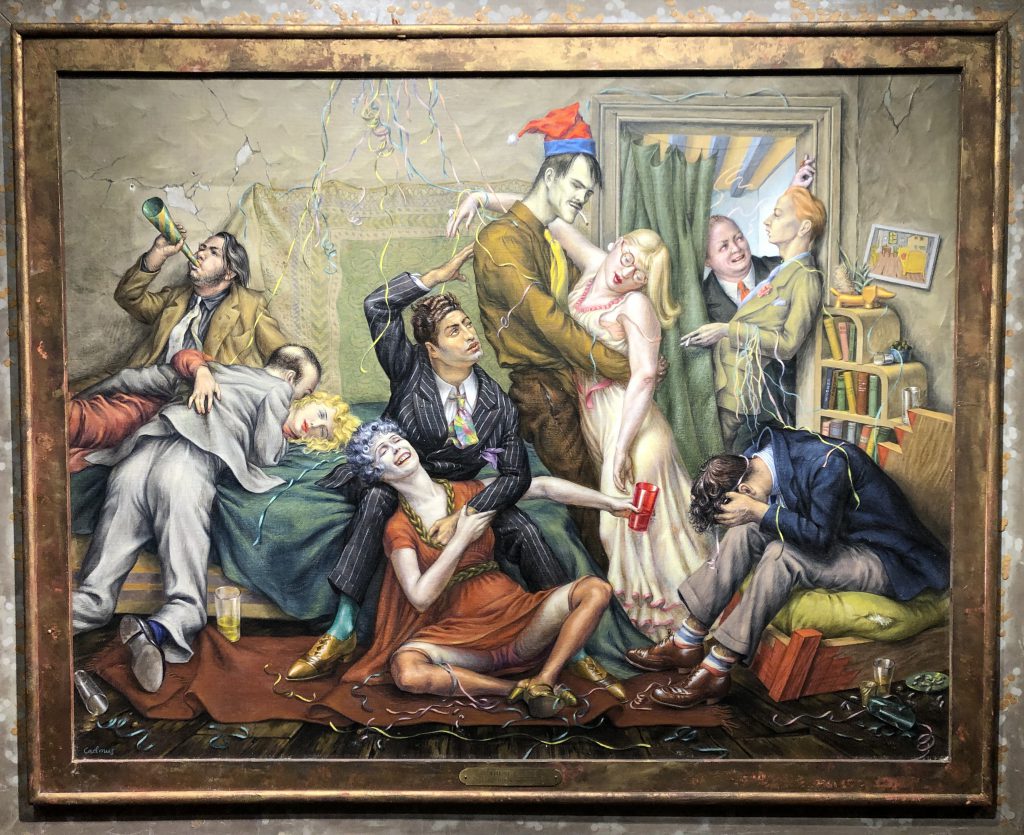

Oil and tempera on linen

30 by 38 inches

Jonathan Boos Gallery

Photo David Ebony

10. Paul Cadmus at Jonathan Boos

Among the outstanding works in the engaging survey “Psychological Realism”—which include top-notch paintings by George Tooker, Alton Pickens, and Henry Koerner—Paul Cadmus’s brilliant 1939 canvas, Seeing the New Year In, is truly outstanding and unforgettable. This rarely seen work, on loan from a private collection, was produced during Cadmus’s most controversial period, when his satirical images inspired status quo backlash and often censorship. In this work, Cadmus’s look at a boozy, New Year’s Eve bash, encompasses a scathing critique of society—its hypocritical moral codes, inequities, and intolerance—and could not be more apropos today.

@davidebony

@davidebony