The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current retrospective, Alice Neel: People Come First, opened on March 22—just a few months after New York City began distributing vaccines, and still months before most COVID-19 restrictions were lifted. After over a year of social distancing, quarantines, and mask mandates, the opening of the show, which largely featured portraits, felt naturally apropos for the moment. After avoiding people—even those closest to us—and with everyone’s faces obscured by masks for so long, the ability to gaze at Neel’s striking depictions of diverse individuals—conveyed through a personal, even psychogenic, lens—was an intellectual and visual salve for the trials of the past year and a half.

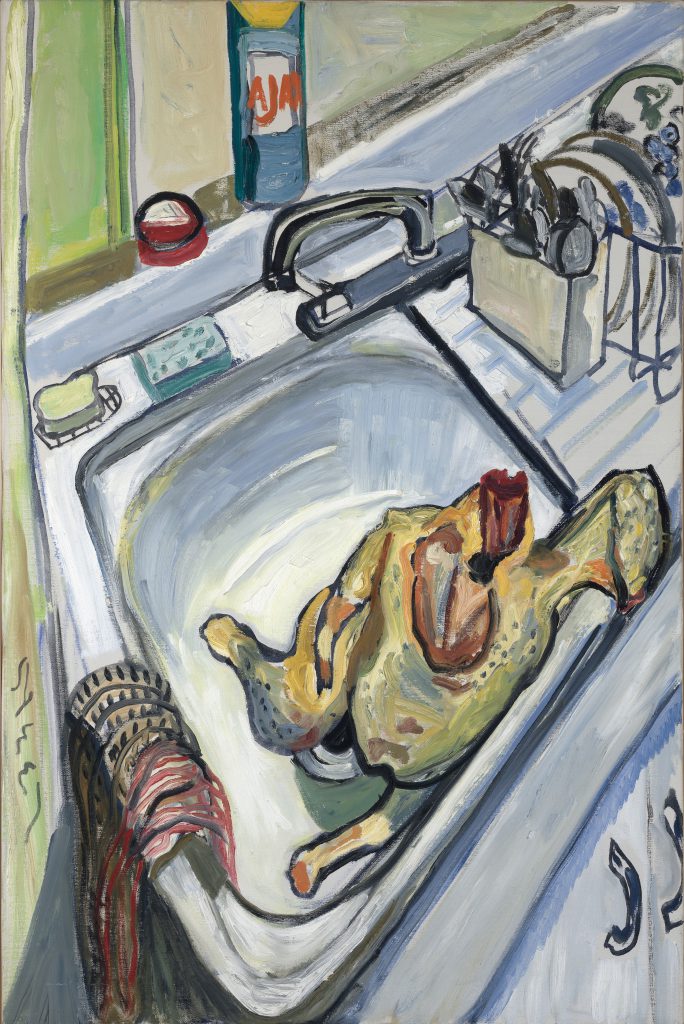

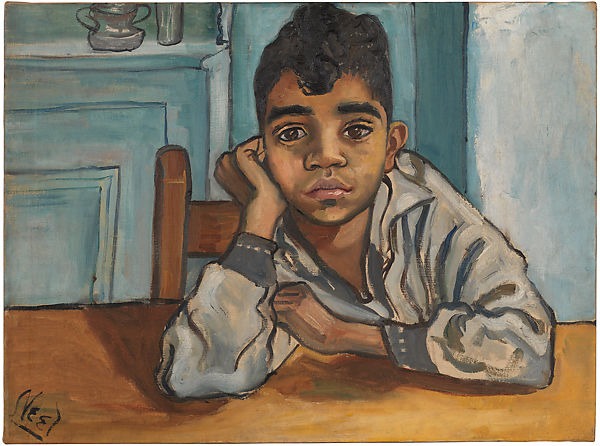

The exhibition (on view in New York through August 1) is organized thematically, with individual galleries dedicated to recurring subjects within Neel’s oeuvre, such as “New York City,” “Motherhood,” and “Home.” As the exhibition progresses, the Met’s curators who organized the show—Kelly Baum, Cynthia Hazen, and Leon Polsky—make a rather strong argument for not only the strength of Neel’s artistic acumen, but also its place within the art historical canon by way of including works by other artists in the fifth gallery titled “Art as History.” Though certain juxtapositions lend insight into how and where Neel’s work fits within the art historical lexicon, such as the inclusion of Chaim Soutine’s Still Life with Rayfish (ca.1924) paired with Neel’s Thanksgiving (1965), other inclusions seem forced and lend themselves to unnecessary comparison. For instance, Robert Henri’s iconic Dutch Girl in White (1907) hung near Neel’s Spanish Boy (1955) only seems relevant in that both artists feature a child wearing predominantly white, or the singular photograph of Gottfried Brockmann taken by August Sander simply showing a sitter in a similar seated position as some of Neel’s subjects.

The Brand Family Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

Though born in the suburbs of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1900, Neel was decidedly one of New York City’s own. She moved to Greenwich Village in the 1930s—then an art world hub—before she eventually turned away from what she considered the downtown snobbish and arcane milieu in favor of Spanish Harlem, and later the Upper West Side, where she lived and worked for over four decades until her death in 1984. Uptown, Neel focused wholly on the city, both its physical characteristics as well as its inhabitants. She painted portraits of friends, neighbors, and even strangers she met on the street, rendering each with an evolving style that vacillated between figuration and abstraction. Paintings of the city itself are of often overlooked vantage points, such as a cropped bank of apartment building windows or the entrance to a subway station at night. Her choice of subject matter was as unique as her style and, in a way, qualified her as a subjective documentarian of sorts.

Over her decades-long career and even today, critics have noted that Neel and her work have not garnered the same widespread attention and acclaim as some of her contemporaries, like Grace Hartigan or Fairfield Porter. Though Neel’s work has been exhibited widely elsewhere in the United States and abroad, this retrospective is only her second at a museum in New York City (and first since her death), with her first having been held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974. One explanation is that at a crucial period in her career, in the 1950s and 1960s, Abstract Expressionism and post-painterly abstraction were the prevailing trends, proselytized by then reigning critic Clement Greenberg. Further, though Neel was predominantly known as a portraitist, her subjective and stylized renderings of sitters, often presented against varied interrelations of figure and ground, prove to be somewhat of a categorical enigma that has seemingly eluded critics and curators. Neel, herself, rejected the terms “portrait” and “portraitist,” instead preferring “pictures of people” and “collector of souls.” Add to this an evolving and idiosyncratic artistic style, and her work stands alone.

Viewers encounter a surprising juxtaposition in the show’s first gallery, which features one of Neel’s earliest works, French Girl (1920s), paired with one of her late paintings rendered in her signature style, Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978)—a coupling that draws sharp focus on Neel’s artistic range and stylistic evolution. Completed during the years she attended the fine art program at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now the Moore College of Art), French Girl seems almost out of place visually within the context of the exhibition. The work shows the prevalent influence of early-20-century academic styles and, perhaps, even salon paintings of the 19th century. In contrast, Margaret Evans Pregnant is rendered in a much looser, impressionistic manner. Though care has clearly been given to the applications of paint that compose the tone and shadow of Margaret’s skin and figure, they appear in stark contrast to the quick, aggregations of painterly strokes in the background. Likewise, the floor is composed of dappled swaths of cadmium and ochre, while her shadow is roughly delineated in light cerulean. This same hue is used to outline the figure of Margaret. The technique uncannily makes her appear to glow from within the canvas. This effect lends itself to the distinctly emotional quality of virtually all of her paintings of people and explains, at least in part, her resistance to the word “portrait.” Portraits are at their essence renderings of someone’s physical presence; but, for Neel, that was only half of the endeavor; Neel treats the emotional state of each sitter as integral to their portrayal. Here, Margaret is radiant with her pregnancy, her eyes clear and bright, a small smile on her face, staring openly toward the viewer with what can only be described as a sense of peace, and perhaps optimism.

Right: Alice Neel. Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas, 57 3/4 x 38 1/2 in. Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. © The Estate of Alice Neel

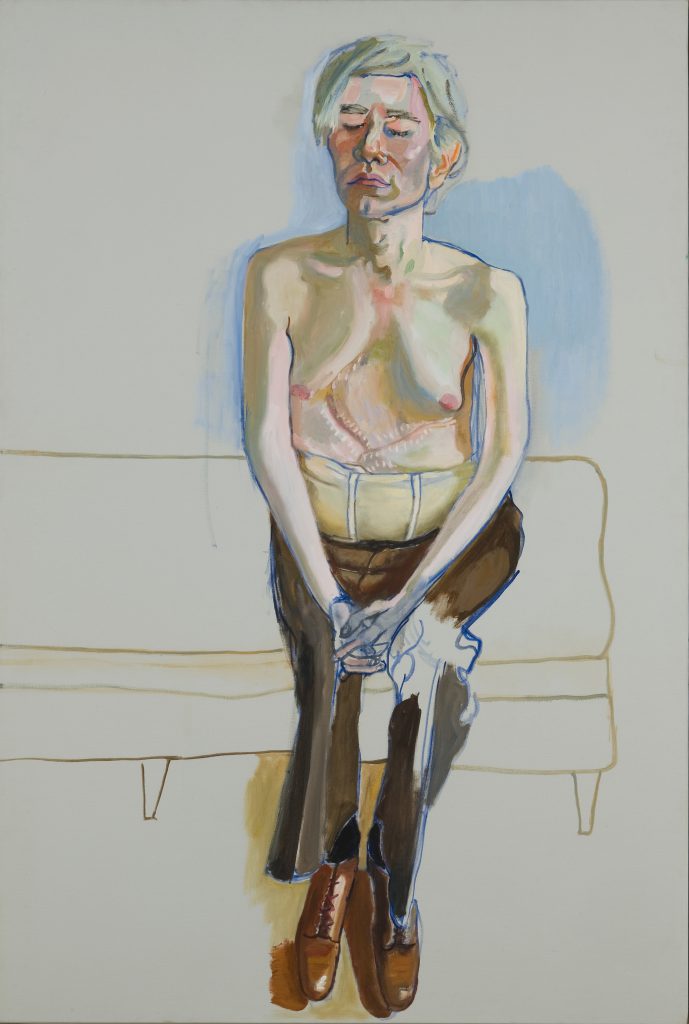

Though Neel made a conscious effort to move away from the hype of the downtown art center, icons of the mid-century art scene frequently made their way up to sit for her. Gems within the show include pictures of artists Andy Warhol and Robert Smithson, and art critics Linda Nochlin and John Perreault. However, Neel’s portraits of everyday New Yorkers are more intriguing. Fascinating in their own right, they elicit an emotion-based analysis (perhaps because the sitters are less guarded or less consciously aware of the artist’s eye than their art world counterparts), allowing for a reading of style and technique that might otherwise be distracted by the celebrity presence within the frame.

Right: Alice Neel. Andy Warhol, 1970. Oil + acrylic on linen, 60 x 40 in. Whitney Museum of American Art. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

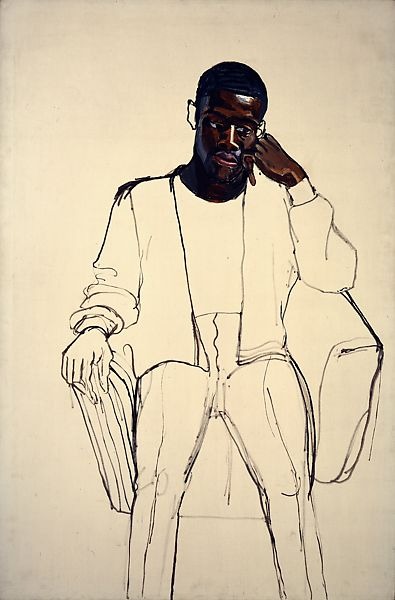

The strongest example of this genre is hung in the final room of the exhibition, Black Draftee (James Hunter) from 1965, two years after the United States’ Vietnam War draft was enacted. Neel met Hunter on the street, and she asked if he would sit for a painting that would be completed in only two sittings. Hunter’s face is portrayed in Neel’s signature late style—painterly with an emphasis on emotion shown through facial expression. The rest of his figure and the background were hastily sketched out over the first sitting, but he never returned for the second (no one know why or what became of him). Initially, Black Draftee remained an unfinished piece, however, after some time Neel made the conscious decision to deem it a finished work, and she signed it and exhibited it. This decision, and the intention behind it, perfectly exemplifies how the definition and categorization of “portrait” proved tangential to Neel’s endeavor. In a 1974 review for the New York Times, critic Hilton Kramer observed (rather obtusely) that Neel’s backgrounds were the product of incompetence or diminished attention span. Black Draftee, however, confirms that the opposite is true (and amply allows for retrospective analysis from the same vantage): despite producing backgrounds with less detail and precision, the full scope of each canvas is still an intrinsic part of the sitters emotional as well as physical context. For Black Draftee, the style and execution of the work’s background is laden with as much of the painting’s expressive content as the fully realized depiction of Hunter’s face; James’s face is surrounded by empty planes of raw canvas with only a few marks to indicate where he sat—a stark metaphor for the draft, and what it took.

The show is not overwhelmed with didactics or rigid readings of each work. Instead, viewers are given the opportunity to discover for themselves (guided by thoughtful hanging) the many facets of her work and even personality. In a way, particularly for New York residents, we can see ourselves reflected in Neel’s “pictures of people”: complex, multifaceted, at times interwoven with our personal histories and struggles that are inevitably seen in our facial expressions and behind our eyes. Though I believe this show would have been successful regardless, Neel’s “collection of souls” is all the more poignant and timelier in the shadow of the pandemic and during our city’s slow rehabilitation.

Alice Neel: People Come First is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fifth Avenue, through August 1, 2021. The show will travel to the Guggenheim Bilbao, September 17, 2021–January 23, 2022, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, March 12, 2022–July 10, 2022.

Quality content i was having second thoughts about this i did not know that congratulations, you can see that the subject has been deepened.

Your website is amazing congratulations, visit mine too:

https://strelato.com

.