Taking Venice, directed by Amei Wallach

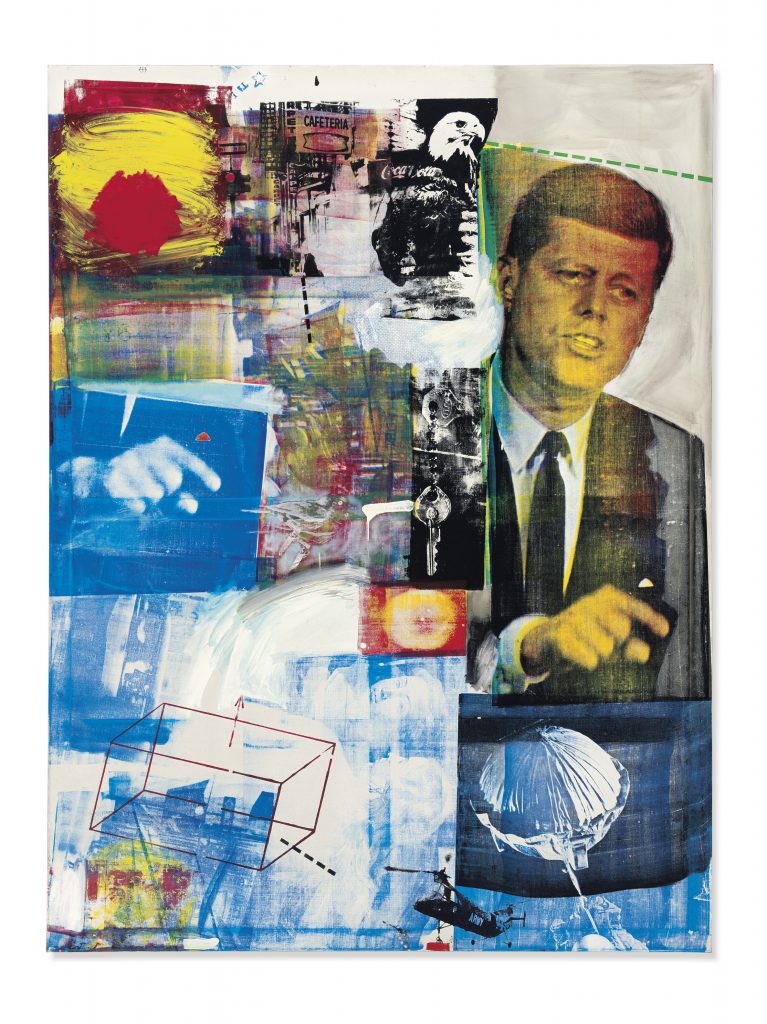

Eight years in the making, Amei Wallach’s new documentary, Taking Venice, focuses on the 1964 Venice Biennale. That year, the US Pavilion, exhibiting the groundbreaking paintings and mixed-media assemblages called Combines by Robert Rauschenberg, won the Grand Prize, then known as the International Prize for Painting, the most prestigious award the long-running international art exhibition has to offer. The decision, and lasting impact, to have awarded this prize to Rauschenberg is difficult to overestimate. It heralded American art and artists as the new, true avant-garde, and signaled that New York City had definitively superseded Paris as the center of the contemporary art world. Some European journalists and other art world observers at the time, however, cried “foul play” and accused the US government and art world accomplices—including New York-based mega-dealer Leo Castelli and Washington D.C. insiders like Alice Denny, a close friend of the Kennedys—of engineering the victory by unorthodox and stealthy means that uncannily paralleled Cold War politics and strategies.

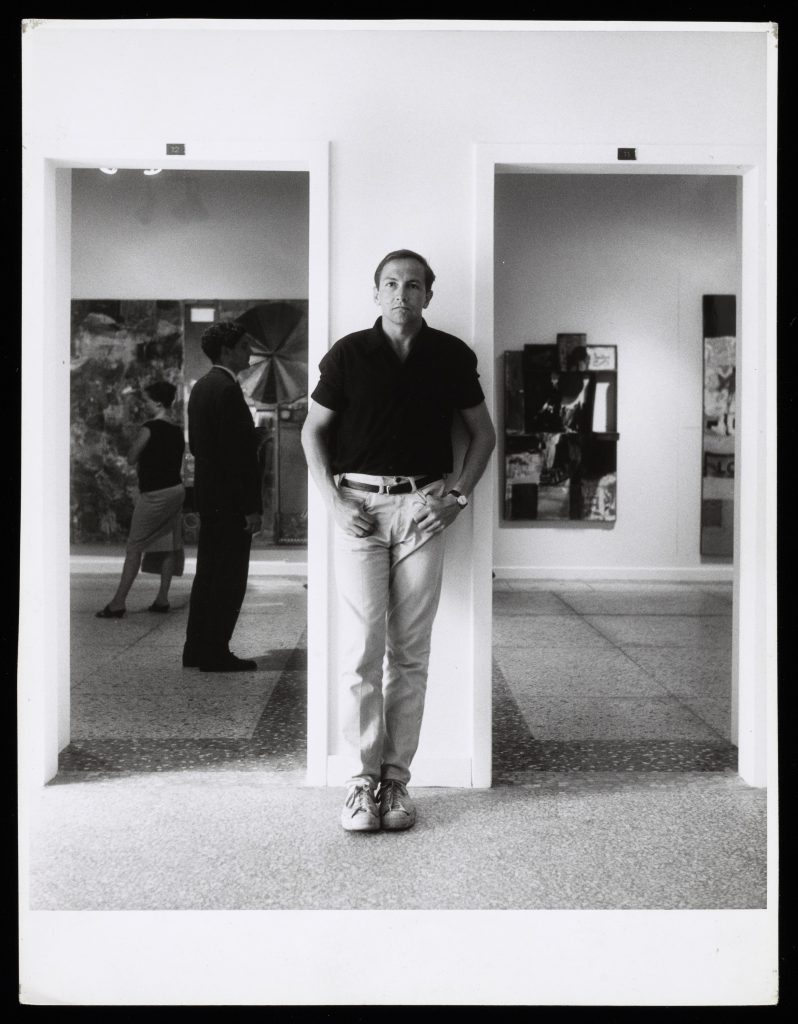

Photograph: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute

Engaged with a cinematic genre that she has long admired and tried to emulate in Taking Venice, Wallach approaches her subject as a kind of caper. Enhanced by edgy incidental music like that of a spy movie and (slightly overused) animated graphics mapping out the developments and highlighting characters, the stage is set for a world of art espionage. The US presence at the Biennale was primarily funded for the first time that year by the government, via the offices of the United States Information Agency [USIA], a branch with wide-ranging cultural initiatives aimed in part at raising the profile of the US abroad, dissolved in 1999. Prior to 1964, the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was funded by private donors, museums, and art galleries, as it is today. In 1964, however, government resources were available to Rauschenberg and his team, including a military cargo plane to ship his large-scale paintings and intricate constructions to the Biennale. That move alone caused considerable consternation and even condemnation by some members of the European press.

Countering this cultural controversy, the assassination of President Kennedy in November of 1963, had provided instead a great deal of pro-American sentiment in Europe at the time. Wallach addresses that sentiment with voiceovers and archival footage, but the film remains centered on the Rauschenberg tumult at the Biennale. An impressive roster of art world talking heads adds nuanced opinion and more detail to the story. Writers, critics, and curators Calvin Tomkins, Robert Storr, Louis Menand, Christine Macel, and Irving Sandler offer insights into the historical importance of the 1964 US Pavilion, as artists Christo, Mark Bradford, Carolee Schneeman, Shirin Neshat, and Simone Leigh highlight the significance of the Biennale. The Italian Michelangelo Pistoletto appears as one of the only foreign artists profiled in the film. His presence onscreen underscores the fact that the film otherwise pays little attention to the rival artists in contention for the Grand Prize at the Biennale in 1964; and the artists’ milieu in Venice that year is, unfortunately, left unexplored.

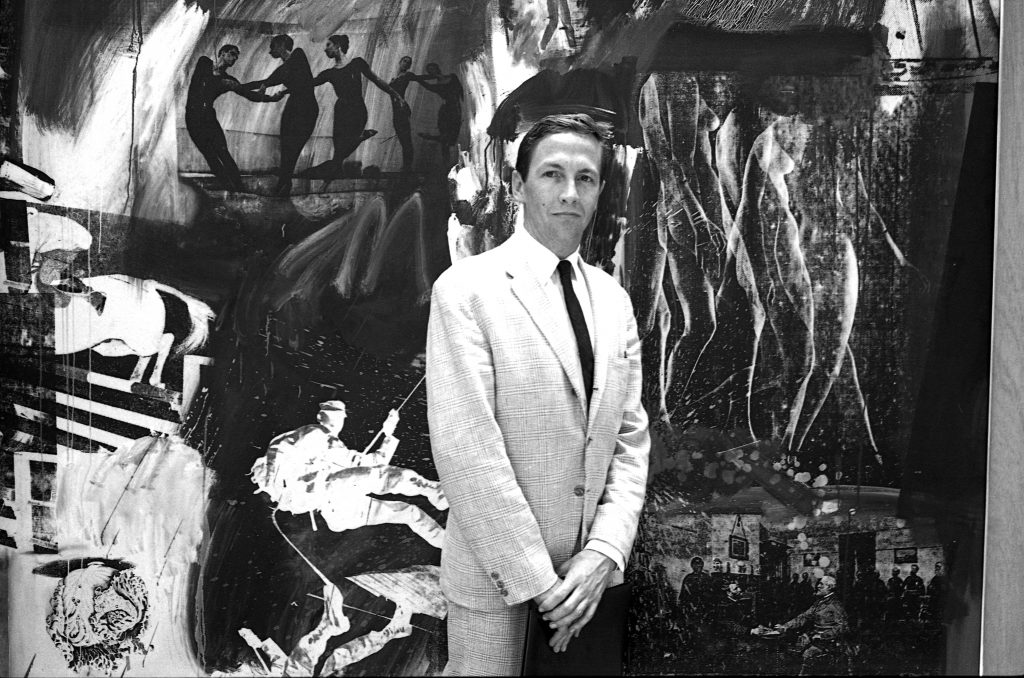

International Biennale of Art Exhibition, Venice, 1964.

Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved.

Prior to Taking Venice, Wallach, an art critic, journalist, and filmmaker, produced well-received documentaries on artists Louise Bourgeois (2008) and Ilya and Emilia Kabakov (2013), and here, she simultaneously keeps the focus squarely on the art and life of Rauschenberg (1925–2008). Wallach knew Rauschenberg, having interviewed him several times and visited his studio on Captiva Island in Florida. The film is a deeply felt tribute to this unique and extraordinarily influential artist. Rather than a caper, the strength of Taking Venice lies in the rare and stunning archival footage that Wallach was able to secure for the film, often with the cooperation of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Little-seen still photos and film footage of Rauschenberg—at work, or cavorting with friends and colleagues like Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and many others—make Taking Venice requisite viewing for anyone interested in American art of the 1960s and is an invaluable addition to the still-unfolding history of that pivotal moment.

canals for exhibition at the Venice Biennale. Still from Taking Venice.

Taking Venice (2024) is directed by Amei Wallach and distributed by Zeitgeist Films in association with Kino Lober. Currently playing at the IFC Center in New York City, where it made its US debut on May 17, it opens in select theaters across the country on May 24. Running time: 98 minutes.

—David Ebony