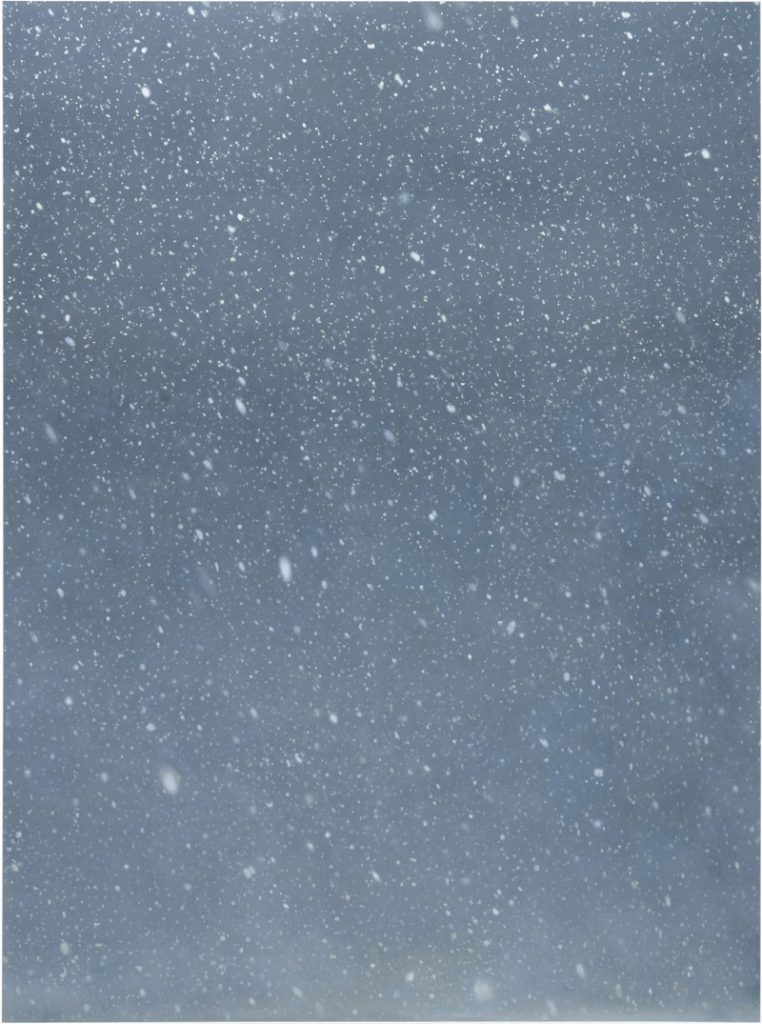

1. Vija Celmins at Matthew Marks, through April 6.

In her refined visual language of similitude, Vija Celmins has long explored the perilous border between truth and illusion. This is a particularly poignant enterprise in the present era of AI. The boundaries between reality and artifice blur in her studies of starry skies, roiling ocean waves, crusty patches of earth, glistening rocks, or spider webs. The first show of new work in six years, Celmins’s Winter features a stunning array of large-scale paintings and several sculptures in painted cast bronze and stainless steel. A prominent motif in the paintings are nocturnal snowfalls—allover compositions on canvas with slick surfaces made of countless layers of oil pigment.

One found object and one made object: powder pigment and binder on bronze, with artist’s pedestal. Photo courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

At 85, the Latvia-born American artist is creating some of the most ambitious work of her long career, including the gorgeous Snowfall (blue), at over 8 ½ by 6 feet, the largest painting she has ever produced. The subtle touches of pale blue light—snowflakes—flicking over the surface, create a hypnotic effect. The painted images teeter between photographic perfection and pure abstraction. Meanwhile, the meticulously wrought 3-D works—ropes, stones, and the long cane of a very thorny rose bush leaning vertically against one wall, offer the viewer a rather exhilarating reality check. The pair of stones comprising the sculpture Two, for instance—one real, and the other a bronze casting from 1977, and painted last year —are impossible to differentiate, unless you are gifted with extrasensory perception.

2. Robert Grosvenor at Karma, through March 2.

Lately, veteran New York-based sculptor and installation art pioneer Robert Grosvenor has been exploring the metaphorical possibilities of found motor vehicles, which he refurbishes not as practical means of transportation, but as uncanny works of art. At the 2022 Venice Biennale, he showed an untitled work consisting of a red motor scooter absurdly glowing within the interior of a metal freight container whose walls were covered in glittery gold. Last year, Grosvenor presented an untitled installation of a bright orange-red Volkswagen-like wheelless car accompanied by ten battered white bowling pins with red bands around the necks, like chicks following the mother from a strange bird species.

Photo courtesy Karma.

In this most recent show, the artist features two untitled 2023 works—one a minimalist wall sculpture of a long horizontal wood blank spray painted black; and in the middle of the room, a purple-painted 1930s Willys sedan with hubcaps and headlights painted black. Goggles nonchalantly placed over the steering wheel, and a rabbit foot keychain in the ignition are all that remain of the absent driver. As the wall hung work suggests a blacktop highway, the spooky roadster, at once nostalgic and futuristic—perhaps endemic of our time—is clearly on the road to nowhere.

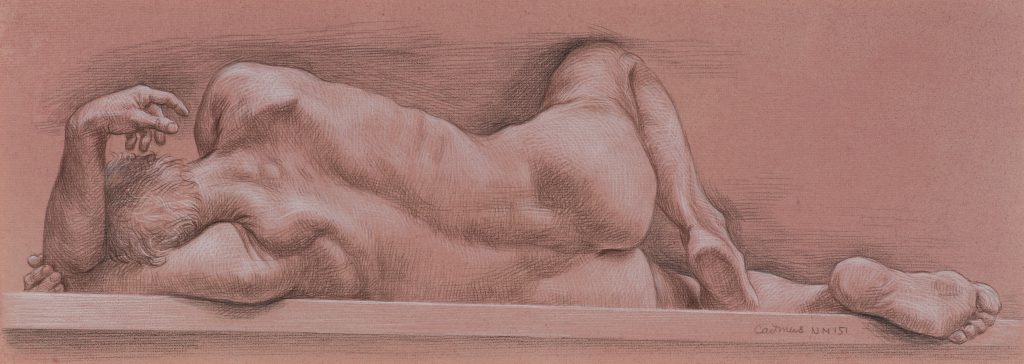

3. Paul Cadmus at DC Moore, through March 16.

For more than twenty years, art audiences have been deprived of a major solo exhibition of works by Paul Cadmus (1904–1999). That is a pity because, as evidenced by this exhibition, Cadmus should be an integral part of today’s discourse regarding gender, sexual identity, and a wide range of LGBTQ+ issues, including homoeroticism in recent art. Early in his career, Cadmus was associated with an avant-garde mode of Magic Realism, but by the mid-twentieth century, his works were sometimes dismissed by critics as being retro, reactionary and twee. The works today, however, once again appear fresh and vibrant.

Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude, contains dozens of the artist’s refined renderings of the figure on hand-toned paper, demonstrating his mastery of Renaissance techniques. Also on view is an informative documentary featuring the articulate and charismatic artist explaining his work and process, as well as a selection of Paul Cadmus paintings. Among them, the once-scandalous Y.M.C.A. Locker Room (1933), shows men in various stages of undress engaged in spirited horseplay. The image, which read as a provocative exposé of queer desire at the time it was made, seems rather zany and benignly romantic today.

Three panels, 60 x 120 inches; Photo courtesy Vito Schnabel Gallery.

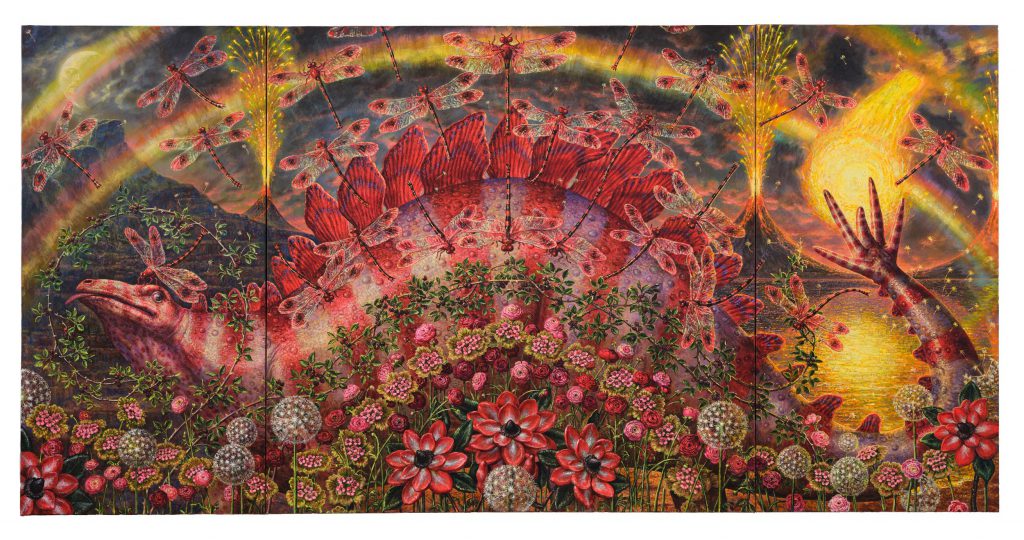

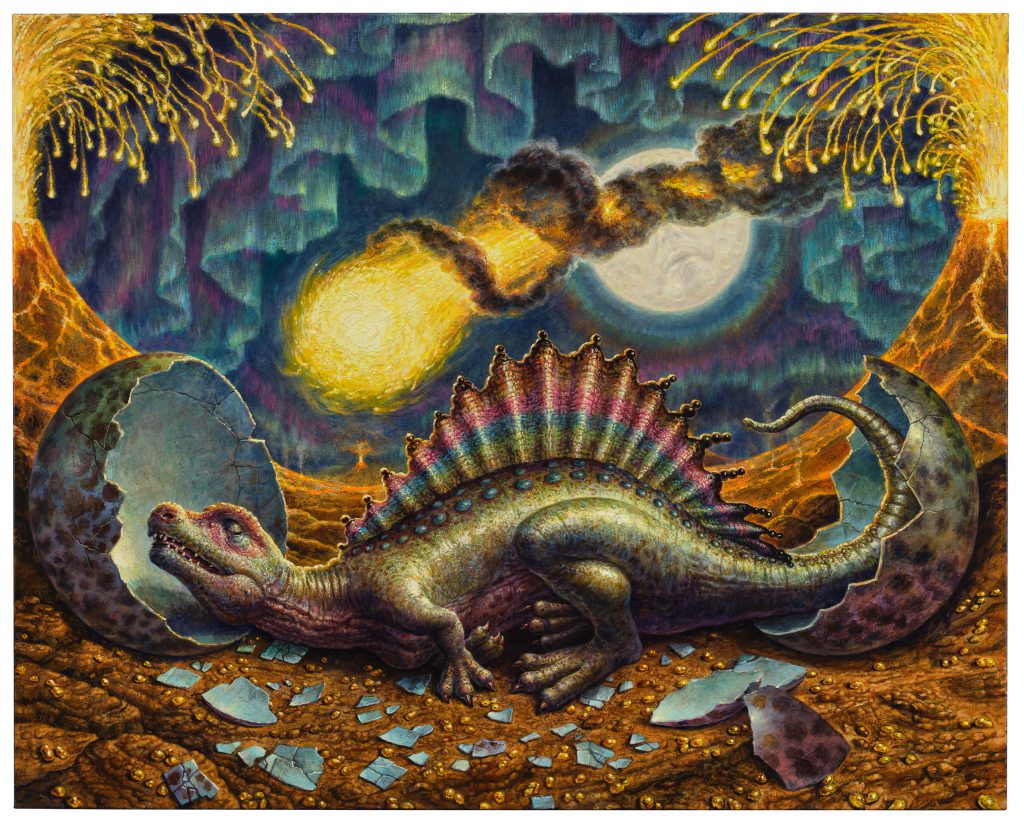

4. Thomas Woodruff at Vito Schnabel Gallery, through March 30.

Thomas Woodruff’s ongoing fantasy of prehistoric, cataclysmic drama reaches a breathtaking crescendo in this show of large-scale recent paintings, The Dinosaur Variations. In full-steam ahead mode, with his arsenal of Renaissance techniques and illusionistic effects serving to enhance these refined, maximalist compositions, Woodruff just might be regarded as the Jurassic Botticelli. Certain works, such as the gorgeous Ruby, appear as shimmering panoramic portraits of queer dinosaurs. In this three-panel painting, spanning five feet high and ten feet wide, a wide-eyed Stegosaurus with red and silvery pink scales lies beneath a glowing rainbow. The creature luxuriates within a sumptuous bed of lush, prehistoric flowers and other vegetation arranged in hypnotic patterns.

© Thomas Woodruff; Photo by Argenis Apolinario; Courtesy the artist and Vito Schnabel Gallery.

Attending this resplendent creature is a bevy of glittery dragonflies, buzzing around the reptilian beauty. It’s not all a bed of roses, however, as a blazing meteor, bursting into the picture plane at right, is about to end the idyllic world that this dinosaur has certainly enjoyed. In this work, as in many others, including Angus D, and the dense and intense Eight Eyes—one of the most striking and challenging compositions here—Woodruff’s sparkling fiction reveals sobering and rather foreboding undercurrents. Themes of climate change, its catastrophic effects, and threats of global annihilation permeate The Dinosaur Variations.

5. Michele Oka Doner at Marlborough, through March 2.

Michele Oka Doner is well known for large-scale architectural projects in the U.S. and Europe, for which she creates unique murals, novel flooring and various other embellishments of public spaces—from museums and office buildings to airports and courthouses. To these often cold and user-unfriendly places she adds images of animal and botanical forms, or sometimes fossil-like shapes, in bronze, other metals, terrazzo or porcelain. These features add a sense of humanity, revelatory awe of nature, and an almost archeological depth to otherwise banal environments.

For The Book of Enchantment, a potent show of recent sculptures and large-scale works on paper, Oka Doner evokes an atmosphere of a primordial civilization—one of mythic and mystical qualities and properties. Her 2-D works here feature silhouetted life-size human figures made of pieces of tree bark inked and embossed upon the surface of the handmade paper. Rather than the direct touch of the human hand, those bits of bark have created these unique and imposing monoprints. The centerpiece of the main gallery, Soul Catcher Installation (2024), consists of an old, rusty metal granary with a rectangular entranceway, like a small hut. Inside the structure Oka Doner hung a grouping of her porcelain Soul Catcher sculptures that resemble small, elongated skulls. The intimate interior of the hut offers a mediative space—for one or two likeminded souls only. There, the artist invites one to contemplate the past, the future, life and death, and, of course, the nature of the spirit. The Book of Enchantment coincides with an Oka Doner solo show at the The Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida.

6. Cindy Sherman at Hauser & Wirth, through March 16.

“The human face is a terrible place. Choose your own examples,” a lyric from Your Own Choice, a favorite old Procol Harum song, ran through my mind while engaging with this latest Cindy Sherman photo endeavor of self-exploration—or exploitation. Unlike previous works in which she portrays various characters or archetypes in elaborate makeup, costumes and wigs, in the latest series (all Untitled, 2023), she focuses solely on the head and face. Here, one of the most successful and influential artists of our time chooses to portray herself in many grotesque guises and modes of facial deconstruction in a collage-like manner. In each work, eyes, mouths, noses have been cut out from various self-portrait source photos and pasted together and reconfigured in bizarre ways.

Untitled 652, for instance, features circular cutouts of color photos of ruby red lips and a bloodshot blue right eye that have been digitally grafted onto a black-and white photo of the artist donning over-wrought makeup and a silvery wig. Ostensibly, the work’s theme touches on the process of aging, but the images on view cannot be self-reflective of this artist’s plunge toward decrepitude and disfiguration. Based on recent photos of Sherman I have seen, in the real world she is aging quite gracefully and handsomely. Nevertheless, the new series can be well appreciated for its formal experimentation. Corresponding to a range of feminist-inflected collage imagery, from Hannah Höch to Deborah Roberts, Sherman adds to the field a photographic language that is similarly adept at complex layering and contradictory—and jarring—spatial relationships. Untitled 647, for example, featuring a personage with an extremely disjointed nose and crooked smile, recalls one of Picasso’s Cubist-tinged wartime portraits of Dora Maar. It has its own kind of eccentric beauty. In Sherman’s way of deconstruction and redemption, the human face may not be such a terrible place after all.

7. Maureen Gallace at Gladstone Gallery, through March 9.

For some years, Maureen Gallace has been producing intimate paintings and drawings of unpopulated and seemingly unsoiled beaches, gardens and verdant backyards, mostly inspired by the environs of coastal New England. Human presence is often suggested, though, by a lone house or barn situated in the luminous landscapes. With their lush, neo-Impressionist-style brushwork and fluid drawing, the works could be perceived as idyllic reveries, or indicative, perhaps, of a form of arcane nature worship. Today, these luminous, bucolic land- and seascapes, as well as blossoming trees and flowers in placid environs, convey to some viewers an urgent plea to preserve the natural environment, and guard against the devastating effects of climate change. Gallace’s air is crystal clear, as in the floral extravaganza, July 14; and the seaside, in works such as the resplendent Pale Waves, is fresh and clean—no plastic bottles or cigarette butts are strewn about on this beach.

The paintings on view here are dense and vibrant, obviously the results of assured touch and an astute color sense. A series of recent drawings on view have a similar precisionist feel, often appearing map-like; and several recall the concise outlines of paint-by-number sets. Yet the works never seem precious or over-wrought. Each brushstroke seems right, and every line exacting. Expanding upon the metaphysical approach of Morandi, and corresponding to other artists she admires—Albert York, Milton Avery and Edward Hopper—Gallace has arrived at a point in her work in which painting and drawing do not merely allude to nature. Each composition instead becomes a special kind of place for receptive viewers—a state of mind, or a unique, mediative environment.

8. Cathy Lebowitz at Skoto Gallery, through March 9.

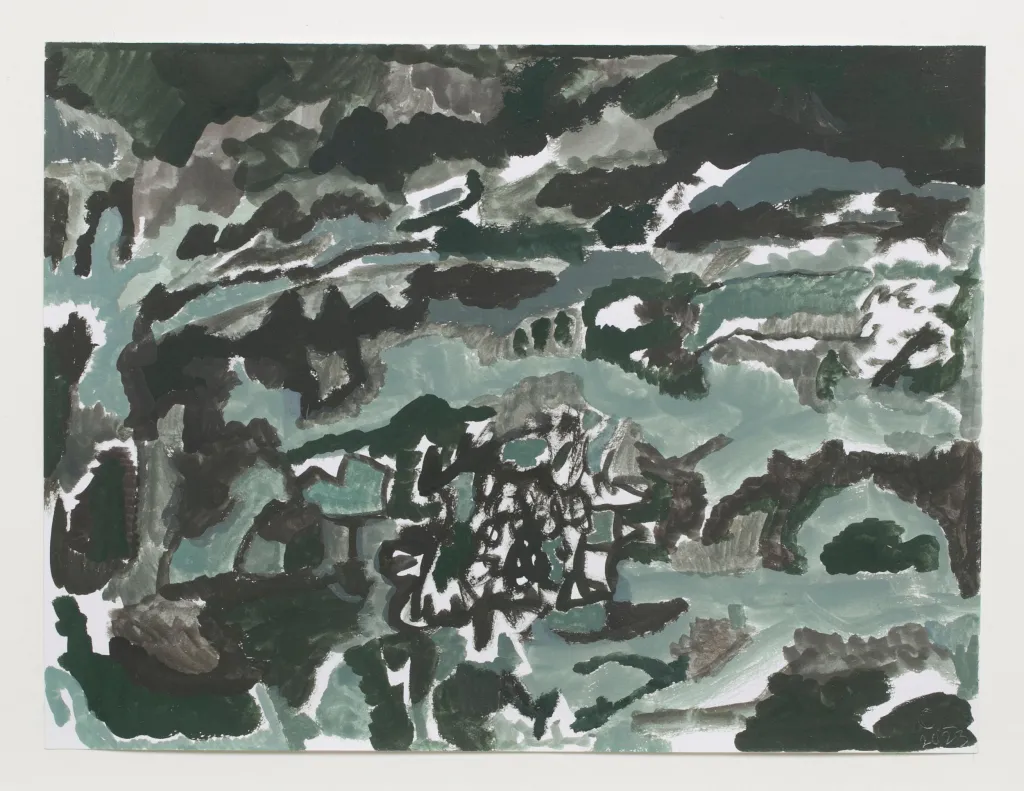

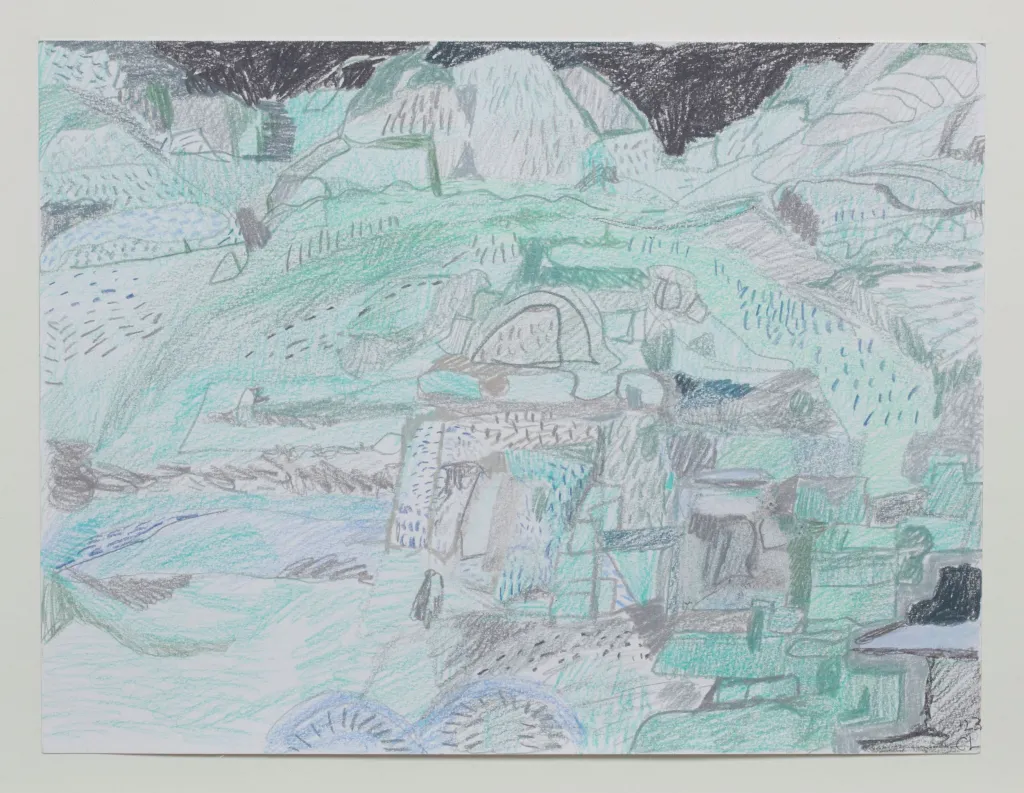

This show’s title, Dark Skies, Rocks, clues the viewer in to the moody timbre of Cathy Lebowitz’s latest series of small-scale works on paper. In her previous solo outing, Lebowitz featured densely layered colored pencil drawings showing quasi-abstract landscapes built upon a rigorous compositional structure of irregular geometric and organic forms. Several pieces in the current show, such as the striking Dark Skies, Rocks XII, relate to those earlier efforts that have a decidedly Cézanne-esque feel. Expanding the technical arsenal at her disposal, Lebowitz has added to the mix the fluid opacity of gouache pigment.

In works such as the formidable Dark Skies, Rocks V, she creates a range of painterly, atmospheric effects to indicate a storm rolling in over a tumultuous, rocky terrain. Lebowitz’s fervid, expressionistic brushstrokes of deep green, black and grays also lend the compositions an intense emotional impact. Throughout the show, the threatening skies might indicate specific cataclysmic weather events. More poignantly, they allude perhaps to the impending threat and dangers of climate change in a forceful yet lyrical way—neither over-estheticized nor didactic.

9. Jose Duran at James Fuentes Gallery, through March 9.

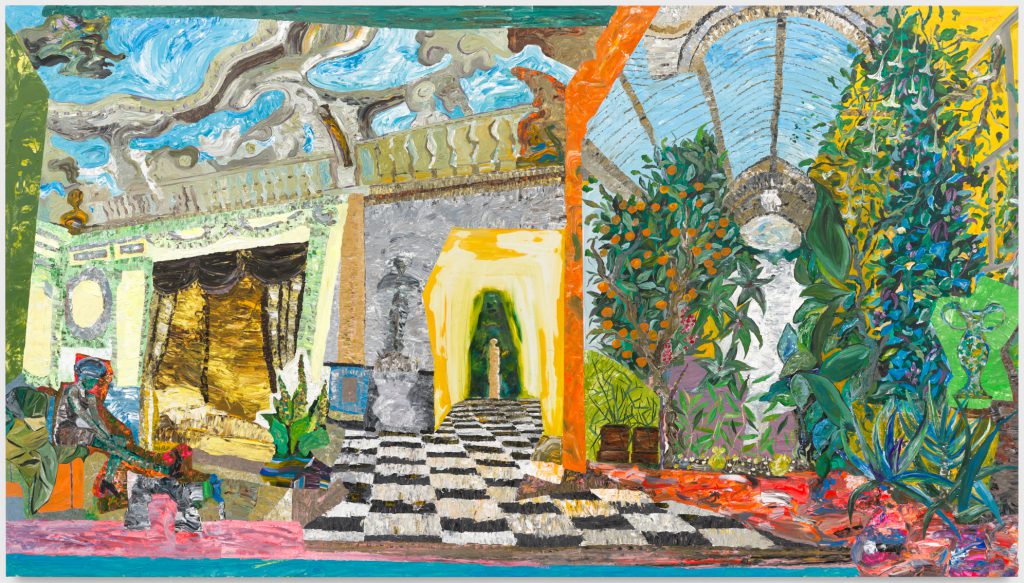

Dominican-born New York artist Jose Duran titled this exhibition of recent works, Elena, in honor of his late mother, and the show pays tribute to the women who helped raise him in the Dominican Republic and in the U.S. In the large-scale acrylic-on-linen works on view, Duran imaginatively imparts to viewers the fanciful and sometimes fantastical places where his mother resides in his memory. Some of the colorful, lush interior scenes, such as Mamma Eddy, are painted with rich impasto swatches of color energetically applied with palette knives and brushes.

They allude to childhood haunts and favorite places, and often include abstracted figures that appear to slowly emerge from the compressed spaces Duran creates. The artist also explores his African Caribbean heritage in these works, sometimes depicting within the ornate interiors local flora, African decorations and medicinal herbs that healers would use. In a press statement, Duran expresses a desire to create in his artworks a place where loved ones can rest in comfort. One can hardly imagine more colorful and welcoming places to spend eternity.

10. David Hornung at JJ Murphy Gallery, though March 9.

Known for his color experiments, and as the author of the influential book Color: A Workshop for Artists and Designers, first published in 2005, David Hornung is also one of the few painters who seem to effortless traverse the realms of figuration and abstraction. For the inaugural exhibition of this Lower East Side venue, Hornung presents a series of new, wholly abstract compositions that explore novel spatial relationships and hybrid shapes. The fusion of geometric and organic forms in each work, rendered with dense layers of oil pigment, often on paper mounted on panel, exude a palpable energy.

Among these medium sized compositions, Trane generates a great deal of tension by the deceptively simple means of a row of irregular black and green rectangles and diamond shapes that horizontally bifurcate the picture plane, which is painted in analogous shades of green and yellow. In Riddle, bright orange diamond shapes at the upper and lower portions of the painting play counterpoint to a purple-blue rectangle trimmed in red, ensconced in a greenish wreath-shaped form that dominates the center of the panel. The longer one looks at this work, the more active it becomes. Throughout the show, Hornung establishes a delicate balance of line and color, as well as a mesmerizing sense of irresolution.

nice selectio. Now I have to run down to chelsea to see thiis group. Thanks, AB

Thanks Annette! Happy gallery going!