We are now witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record. An unprecedented 70.8 million people around the world have been forced from home. Among them are 25.9 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18. — The UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “Figures at a Glance,” June 18, 2019

This text above is displayed on the cover of the brochure for the Displaced exhibition.

Displaced: Contemporary Artists Confront the Global Refugee Crisis—organized and co-curated by Irene Hofmann, SITE Santa Fe’s Phillips Director and Chief Curator and Brandee Caoba, Assistant Curator—was scheduled to open in March 2020 at SITE, but the exhibition never had a chance to actually go on view. The doors were closed until the following September because of the pandemic. No impressions of and reactions to the exhibition materialized for almost six months as the world began to collectively go into shock and cancel mode along with the gradual acceptance of mask wearing and social distancing. That said, this dense, heartbreaking, and compelling show at SITE could not have come at a better or a worse time, inadvertently mirroring the myriad ways we have all become displaced from our usual spaces of support and refuge.

We are all in the displacement zone now, but how does our “new normal” life in America, for example, even begin to compare with the experiences of the globally dispossessed who embark on long and dangerous journeys to escape war, famine, hopelessness, and inequities of every persuasion? A fair degree of disconnect ensues for the viewer in a contemporary art space that attempts to simulate the reality of dipping one’s toes into migratory waters and slogging through toxic refugee camps filled with people who are desperate to survive another day, and, with any luck at all, journey on to a better life and prospects in some European country that, in fact, doesn’t want them.

When Displaced finally opened in autumn, there was already enough misery to go around that had nothing to do with people fleeing from places like Syria, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Iraq, Pakistan, Mexico, or El Salvador. And what could be more ironic than to sit in a safe darkened room, in comfortable, socially-distanced seats, and watch Ai Weiwei’s movie Human Flow (2017) with its searing realities and horrific statistics: sixty-five million people displaced in these contemporary migrations—the largest amount of humans on the move since World War II. Throughout Ai’s film, there are people endlessly walking in an episodic, flowing river of human beings looking for a place—looking for shelter in some promise land never promised, and hardly attainable—with the elusive goal of survival.

To enter into the dialectics of Displaced, by way of Human Flow, was no easy task. There is segment after segment of tent cities along railroad tracks in the pouring rain, waiting for the authorities to summarily arrive and begin to tear everything down: the old, the young, the infirm, babies, and children forced out into the elements once again. There are sequences of destitution beyond measure, as bodies float in Mediterranean waters, only a short distance from overcrowded boats or rubber rafts, packed solid with people full of terror and longing. One of the saddest scenes, in a work of immense and protracted sadness, was, ironically, watching a boatload of African migrants get rescued in the frigid night air—escorted, and in some cases lifted from their rickety craft and then wrapped in luminous space blankets to warm them up—everyone freezing, hungry, and in shock. It becomes difficult to go on watching the parade of wretchedness in Human Flow, but once in the exhibition, we are compelled to participate, however vicariously, in the constant sorrows and misery of migration. Some of the words, spoken by a migrant rescued in the Mediterranean, were these: “I am that sea and have come into a bowl…”

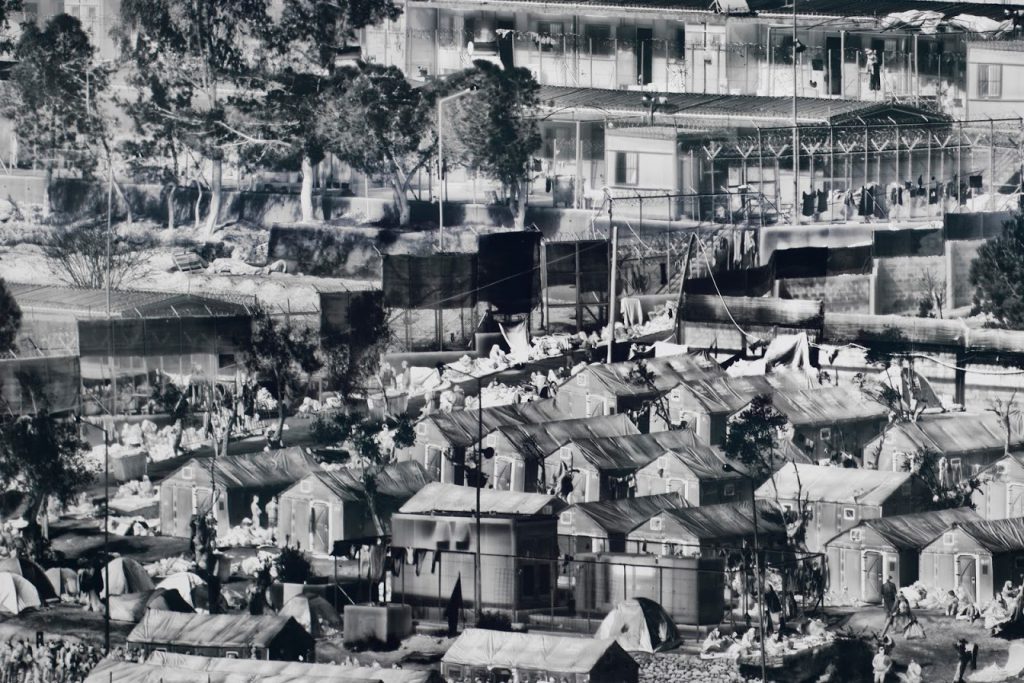

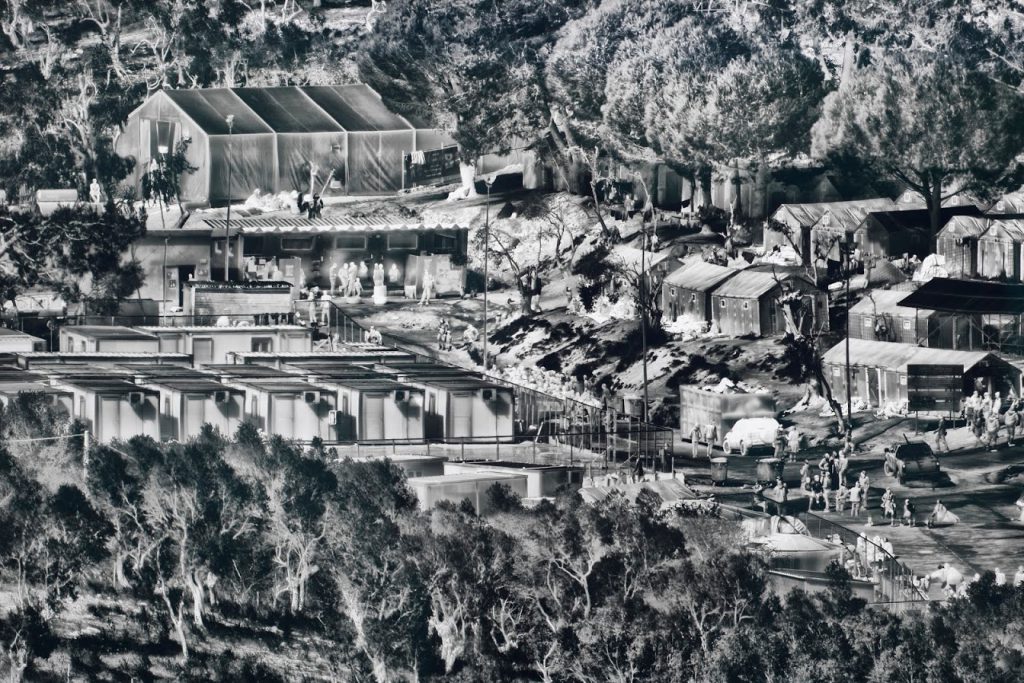

I had begun taking notes about the exhibition in September which also features the panoramic photographs of Richard Mosse of refugee encampments such as Moria Camp in Lesbos, Greece. Mosse uses military-grade surveillance technology to create his large-format black-and-white images filled with intricate details of the physical realities of various refugee sites, and it was shortly after Displaced opened to the public that four men set fire to Moria Camp, destroying it. The following text comes from a news release in The Guardian: “Europe’s largest refugee camp is now a rancid pile of charred debris, melted metal frames, gutted communal toilets, and burned rats, lying by potatoes and onions that will never be consumed.” So, the portrait of Moria Camp in the exhibition is of a place that no longer exists.

Jack Sheinman Gallery, New York.

Viewing Human Flow is transfixing however difficult the content, as Ai and his camera move from country to country—different cultures, yes, but the stories in the end are all one story with millions of moving parts. This idea—that at the root level of Displaced is one infinitely heartbreaking saga—is made clear in Candice Breitz’s two-part video installation Love Story (2016). Part one is a six-channel work comprising the narratives of six individuals from diverse origins: Sarah Ezzat Mardini fled Syria; José Maria João, fled Angola; Mamy Maloba Langa, fled Kinshasha; Farah Abdi Mohamed, fled Somalia; Luis Nava Molero, fled Venezuela; and Shabeena Francis Saveri, fled India. The three women and the three men, were filmed in saturated color against green screens and the stories they related are filled with dysfunction, terror, abuse, and violence.

One of the individuals, Luis Nava Molero, now living in New York, is one of the lucky ones, you could say. Once a professor of Political Science at Simon Bolivar University in Caracas, Molero had never been a supporter of the politics of Hugo Chavez and he was increasingly harassed. He was also a gay man and Molero came increasingly under attack for not being a Chavista. At first Molero was only verbally abused, but the abuse intensified and then one night he was physically assaulted at the university. In his video interview with Breitz he said, “What hurt me the most was the thought: I am not safe here—they hate me so much!” And then came the decision to leave Venezuela. “You realize how vulnerable you can be … I wasn’t safe anywhere … and being gay was also a problem.”

I had the chance to meet Molero when he came for a visit to Santa Fe in October, and he talked about his transition from being a well-known professor “to being a nobody—to someone who is invisible.” That said, Molero, an intelligent, highly educated, and articulate man with an engaging personality, has been able to piece together a new life for himself in America, and like I said, he is one of the lucky individuals who was able to escape persecution and get to a country where he spoke the language fluently, already had friends and connections, plus he sought asylum, which was granted, in the time of President Obama and not Trump. The following is a link to Molero’s video interview with Breitz from Love Story:

The work in Displaced is global in scope and includes a wide array of installations by Harriet Bart (USA) and Yu-Wen Wu (Taiwan/USA); Reena Saini Kallat (India); Hew Locke (UK/Guyana); Cannupa Hanska Luger (USA); Guadalupe Maravilla (El Salvador/USA); The Refugee Nation represented by Yara Said (Syria) and Moutaz Arian (Syria); UNITED for International Action’s List of Deaths; and Hostile Terrain 94, a collaboration between SITE Santa Fe, the School for Advanced Research, and the Center for Contemporary Arts, both also located in Santa Fe. Along with the already-mentioned Richard Mosse (Ireland), Candice Breitz (South Africa/Germany), and Ai Weiwei (China/Germany), who feature photography, video, and film respectively, the other artists and activists incorporate a range of media representing sculpture, video, multi-platform installations, straightforward statistics in a list, and the implied sound and fury of the new nomads—all of which is meant to evoke a set of cascading associations not easy to process. Curiously enough, though, one is often left feeling several steps removed from the underlying theme of Displaced when dealing with the aesthetics of the other installations as opposed to the psychological import of what one has to confront in Human Flow, for example, or the unadorned narratives related in Love Story, or the documentary information in the piece Hostile Terrain 94, about the migration difficulties and tragedies in the Americas.

The other more static installations asked to be viewed in part for their form, their materials; their textures and intricacies—but meanwhile “the human flow” in one of the other rooms pushes and pulls you to pay closer attention to the very reason you are here in this contemporary art space: the shattering stories, the utter devastation, and the profound sense of need that rises up in your face. As interesting and resourceful as Hew Locke’s fantasy boat models are, with their hints of migrant stowaways, or the back-to-the future mode of Cannupa Hanska Luger’s retrofitted van, I felt a sense of detachment from the artists’ emphasis on material choices above and beyond sociological ones. And this detachment from Locke’s and Hanska Luger’s aesthetics was an unintended consequence of the real.

Seeing this exhibition and trying to fathom its scope meant seeing it refracted through a vast lens of pain, anguish, suffering of every description, and destitution. The sheer weight of the evidence of life-and-death matters stopped me in my tracks every time I walked through the tense and dire labyrinth represented by Displaced; I found myself in a perpetual tug of war between the actual and the conceptual, with the implied weight of all the migratory ghosts tipping the scales of my attention and my profound disbelief.

DISPLACED: Contemporary Artists Confront the Global Refugee Crisis is open at SITE Santa Fe through January 24, 2021. https://sitesantafe.org/

Diane Armitage is a writer and artist living in Santa Fe, and has worked with SNAP Editions since 2004.