The Venice Biennale offers a more pleasant and far more potent experience after the feverish Vernissage. During those frenzied preview days in April, critics from around the world descend on the vast and venerable art exhibition, many vying to come up with the most searing slam-dunk dis or stinging verdict. This year’s Biennale—the 60th installment of the international exhibition—organized by Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa, has a gentle core and a slow-paced rhythm. Foreigners Everywhere / Stranieri Ovunque is a show to be savored. It is not the kind of brash, hyper-aggressive presentation that can handily repel the critical onslaught and rush to judgment that resulted in the inordinate number of negative reviews it initially received from some critics and art-world observers.

acrylic felt, cold-rolled mild steel, steel plate, marble base; USA Pavilion; Photo D. Ebony.

Among the major complaints is the fact that nearly half of the 300+ artists are deceased—for a show that is supposed to gauge the pulse of living, vital, international contemporary art. And yes, there are perhaps too many weavings and an overabundance of folksy paintings that recall Grandma Moses—on an off day. Despite these grumbles, there are unexpected confluences, contradictions, and challenges throughout the show. With time and focus, this became for me one of the most engaging and rewarding Venice Biennales of the dozen or so I have seen. Admirably, Pedrosa has taken a lot of risks. The inclusion of so many deceased artists, for instance, was intended as a corrective, to readdress the history of the Biennale and highlight influential artists who had been excluded or shunned by exhibition organizers in years past. This eclectic group, ranging from Mexico’s Frida Kahlo to Indonesia’s Affandi and Italy’s Ester Pilone, provides some of the show’s most memorable moments. Ultimately, the exhibition is exhilarating largely as a result of its innovative reflective attention to the past.

In general, the exhibition’s central proposition—that on some level we are all “strangers in a strange land”—is organized around four basic groups of artists: immigrants, expatriates, émigrés, and exiles constitute one group. The other groups are Indigenous artists, who are made to feel like foreigners in their own land; Outsider artists, self-taught or folk artists who work at the fringes of the art world; and Queer artists, or all of those who have, according to Pedrosa in his Biennale catalogue essay, “moved within different sexualities and genders, often being persecuted or outlawed.” Pedrosa, who identifies as queer, therefore has both a personal and professional stake in the exhibition.

Pedrosa’s thematic gambit clearly permeates both of the exhibition’s main venues—the Central Pavilion of the Giardini and the nearby cavernous Arsenale. The theme also inspired off-site exhibitions, as well as many of the national pavilions in the Gardini, including the United States pavilion featuring the work of Jeffrey Gibson. Of Cherokee descent and a member of the Choctaw Indians, Gibson is the first artist of Native American heritage to solely represent the US at the Biennale. His bright, brash, and colorful exhibition of paintings, sculptures, and video work—with many design motifs borrowed from Native American art—is one of the Biennale’s highlights. This exuberant exhibition should have won the Golden Lion for best national participation, but the celebratory tone of Gibson’s show is a bit out of step with the politically fraught mood of the Biennale this year.

It was no surprise, then, that the somber and elegiac show at the Australian pavilion won the Golden Lion for best national pavilion. Archie Moore’s exhibition features an immersive “family tree mural,” tracing his Indigenous roots back many decades, with hundreds of names of distant relatives etched in white chalk on black-painted walls. While impressively labor-intensive, the effort was, unfortunately, nearly illegible in the darkened space.

Directly next door to the US pavilion, the Israel pavilion, which was to have showcased the work of Ruth Patir, was shuttered by the artist in the wake of pro-Palestinian demonstrations, and as a call for peace in the region as the war in Gaza rages on. The Russian pavilion also remains closed for the second Biennale in a row, since the country’s invasion of Ukraine.

Among the more inspiring national pavilions is Egypt’s solo show by Alexandria-based artist Wael Shawky. Imposing sculptures dominate the space, including tall vitrine-like cabinets filled with Murano glass objects, and a massive work composed of clay, straw, resin, and steel resembling a giant crab or insect. On one wall, a continuous projection of Shawky’s new video Drama 1882 (2024) arrests viewers with a highly stylized, 45-minute operatic tale of an 1882 uprising against Ottoman rule in Egypt. This rapturously received video continues to attract large crowds well into the Biennale’s run.

Hungary’s exhibition of works by Márton Nemes, Techno Zen, features mesmerizing abstract wall reliefs, Day-Glo paintings, and sculptures often outfitted with light and kinetic components, such as computerized LED programs featuring changing-color lights. Some objects even incorporate motion sensors that generate sounds and music compositions unique to each piece. Nemes, a friend and one-time protégé of artist Anselm Reyle, shares with his German colleague an exploration of unorthodox materials and visual puns related to modernism in all its abstract forms.

In contrast to Nemes’s hallucinogenic abstractions, Şerban Savu’s figurative paintings in the Romanian pavilion offer refined, down-to-earth realist images of visitors to ancient sites and historic locations throughout Romania. This series serves as a graceful homage to his homeland, and an elegant merger of painting and architecture. The canvases are ensconced within shallow recesses in the walls created specifically for the artworks by the Romanian design team Atelier Brenda.

One of the delights of the event is the unexpected encounters with unforgettable Biennale exhibitions situated in modest offsite venues. One such treasure trove, the Panama pavilion, features Isabel De Obaldía’s installation of a recent series of small cast-glass abstracted figures suspended from the gallery ceiling that dangle in front of her immersive painted mural depicting the “Darien Gap.” This expansive jungle, which connects Panama and Columbia, was crossed in 2023 by more than 500,000 migrants and asylum seekers making their way toward the US border. De Obaldía’s work is a moving tribute to the many who lost their lives during the perilous journey through the wilderness.

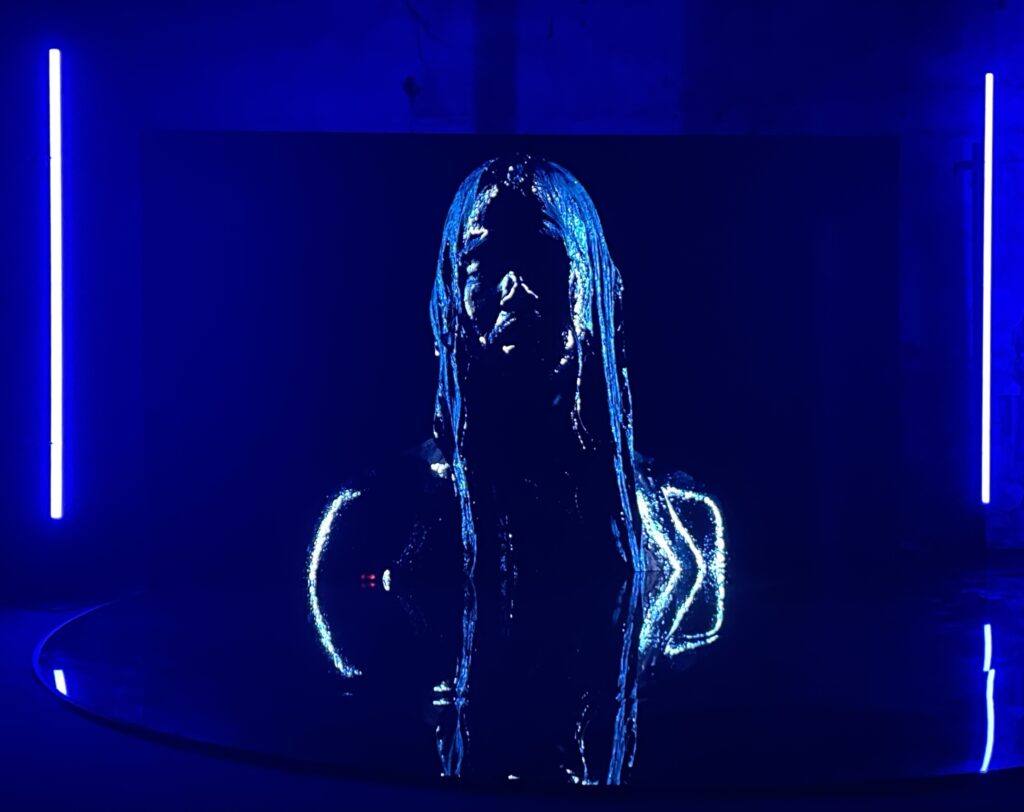

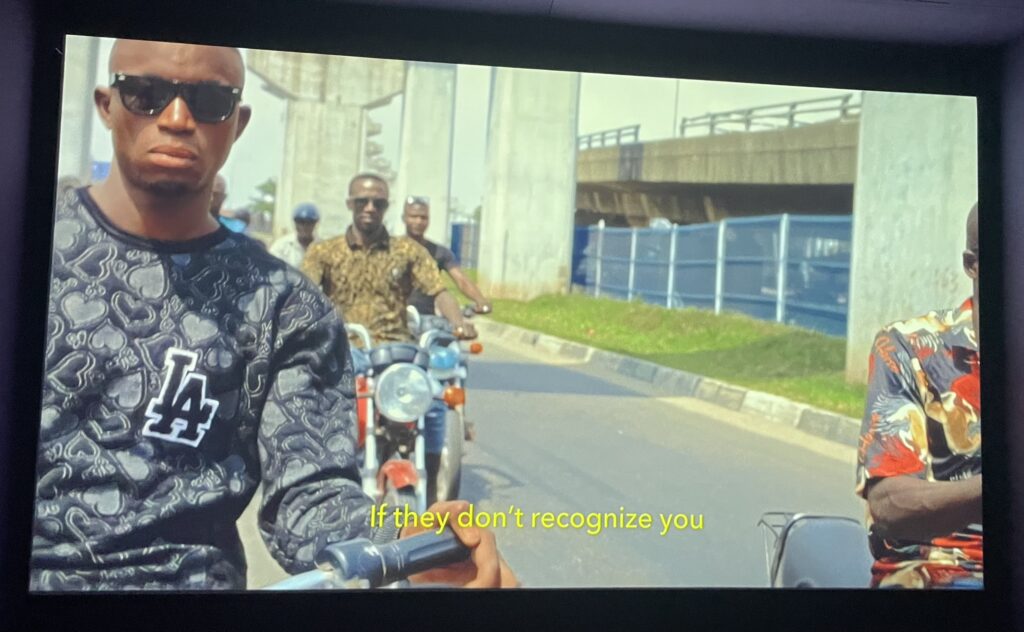

De Obaldía’s installation directly corresponds to the main Biennale theme, along with a number of other works in the Arsenale. Among them is Void (2022) a hypnotizing video installation by Philippines-born artist Joshua Serafin. On a screen bordered by vertical tubes of purple neon, a figure (seemingly androgenous) emerges from a pit of tar-like, blue-toned primordial ooze, offering a new interpretation of gender fluidity. London-born, Lagos-based Karimah Ashadu’s similarly riveting video, Machine Boys (2024), examines a gang of renegade Nigerian motorcycle taxi drivers and their proudly defiant social status as outcasts. The work deservedly won for Ashadu the Silver Lion award for most promising young artist.

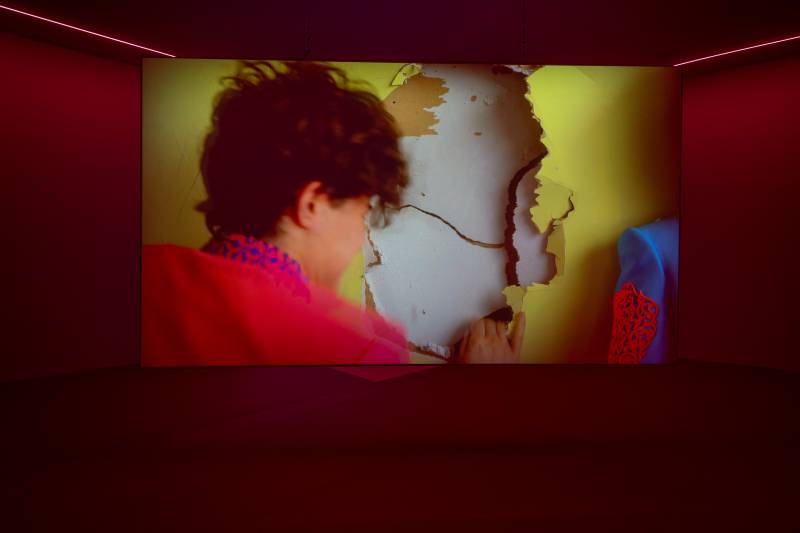

In her lushly colorful video installation Pos’se acaba este contar (2021), Mexico’s Eva Segovia explores male aggression through a disquieting film featuring two men in candy-colored mariachi costumes slapping each other silly. Despite the violence and tough message, it is a total pleasure to watch over and over again. Works of exceptional formal beauty are evident throughout the exhibition, including the monumental woven tapestries by New York artist Liz Collins. The brilliant, cosmic imagery in her works contributes to what she describes as “the fantasy of a queer utopia that is just out of reach.”

The Willem de Kooning Foundation, SIAE; Photo D. Ebony, 2024

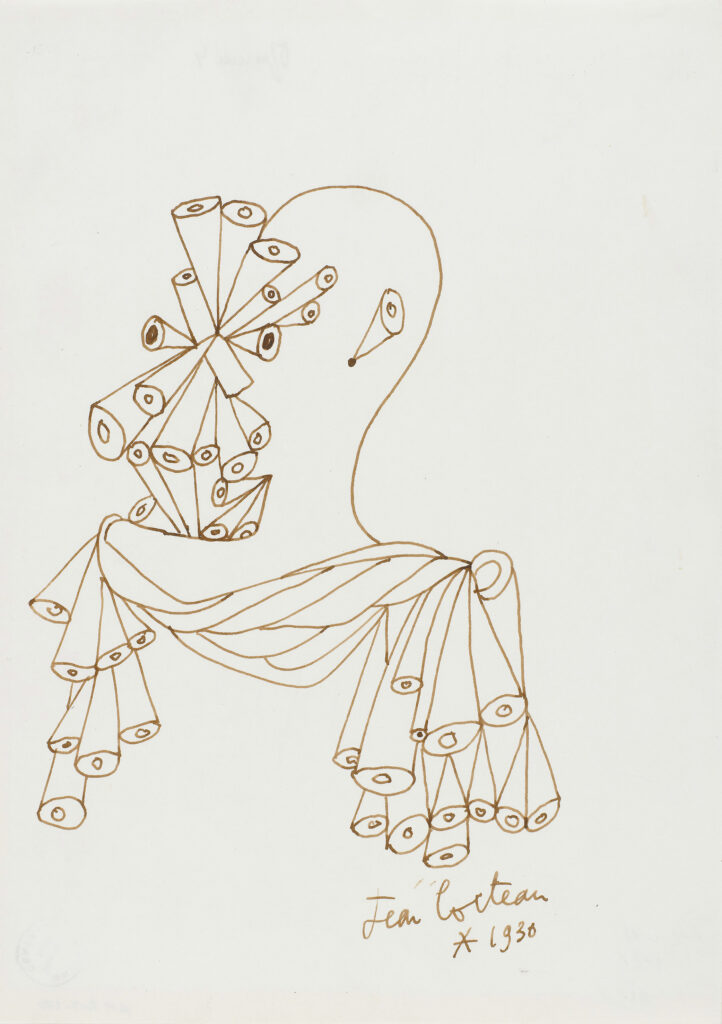

Major exhibitions in Venice coinciding with the Biennale include De Kooning and Italy at the Gallerie dell’ Accademia, a luminous exhibition exploring the AbEx artist’s extended visits to Italy and their impact on his work. Also of note is Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Organized by New York-based curator Kenneth E. Silver, the exhibition explores Cocteau’s queer themes, his battle with opium addiction, and his unique outsider/insider artworld status, directly connecting to the Biennale’s overarching theme.

Toward the end of the Arsenale, the Italian pavilion’s presentation of works by conceptualist Massimo Bartolini, Due qui / To hear (2024), nearly steals the entire Biennale. Bartolini fills one vast gallery with an elaborate scaffolding of metal pipes, transforming it into a gigantic pipe organ using several mechanical bellows. Drone sounds and harmonious tunes composed especially for the piece emanate from the ends of the scaffolding pipes.

The melodious room centers on a circular pit filled with a mechanized, undulating wave of liquid clay. Visitors transfixed by the aural and visual sensations can sit on a circular bench surrounding the pit of muddy waves and contemplate life—or whatever else may strike. There is something deeply moving about this work. One can imagine that if humanity is ever going to be united about anything, it will have to be about something as strange and absurdly beautiful as this.

La Biennale de Venezia, the 60th Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, is on view in Venice, April 20–November 24, 2024.