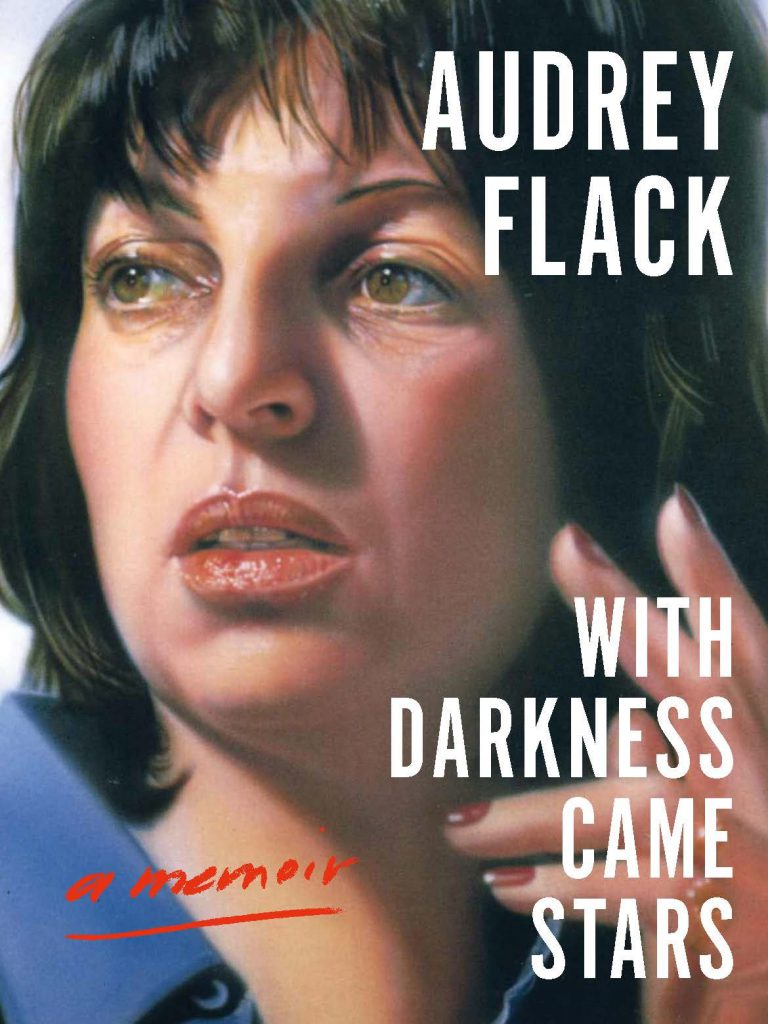

Name-dropping in the art world is a headache-inducing yet often necessary mechanism for gaining social cachet by proving connections to influential circles. This was especially true among the notorious denizens of the Cedar Bar in the Ab Ex-dominated years of the late 1950s and early ’60s. There, as the ninety-two-year-old artist Audrey Flack puts it near the beginning of her memoir With Darkness Came Stars, “shoving, pushing, and even occasional fistfights erupted. Reckless sex, heavy drinking, and drugs were part of the scene.” The fabled downtown hangout swirled with impassioned, inebriated, flirtatious discussions about whose art reminded who of whose art, whose art was on the rise or demise, who was dating whom, who was looking at whom (be it their body of work or actual body). “I was in the center of the action, looking out of the eye of the bull,” Flack writes. “The art world was open to me—but so were the pitfalls of Abstract Expressionist life. It was exhilarating, but also rough and fast.”

In her memoir, wonderfully printed as a book intended to be read rather than as a career retrospective left lying flat on a table, Flack demonstrates that she achieved much in a world long dominated by men—a reality everyone knows, whether they opt to speak of it or not. The milieu that took shape was, according to Flack, an electrifying moment: “Paris was over. New York City was rapidly becoming the international hub of art activity.” Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Piet Mondrian, and Willem de Kooning arrived from Europe. Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock came from the Midwest and Pennsylvania. A kind gentleman named Lou Rosenthal owned a basement art supply store in the East Village and knew “everyone.” When Flack was short on cash and found herself “making meals out of hot water and ketchup” while eyeing particular hues of paint, Rosenthal would furtively slip her a few tubes. “Being pretty mattered,” Flack asserts with conviction and speaking not of the art world, but the realities of being a woman. “Poor Lee Krasner was considered ugly,” she explains of Jackson Pollock’s then-future wife who was also a painter and eventually achieved status of her own through her work, “even though she had a great body, her face was the butt of nasty jokes.”

Flack, born in 1931 and raised in New York City’s Washington Heights, knew intuitively how to operate in the Cedar Bar milieu in part via her mother. Despite her mother’s absence due to a relentless gambling addiction, the family’s apartment was decorated with reproductions of paintings by Rembrandt, Ghirlandaio, Jan van Eyck, Mary Cassatt, Amadeo Modigliani, and Paul Cézanne. Having fervently absorbed the aesthetics of these artists, Flack developed a whimsical notion that they were relatives and friends: “Rembrandt…the grandfather I never had, Mary Cassatt my good aunt, Paul Cézanne my steadfast uncle, Amadeo Modigliani my wayward brother.” Flack independently honed her ability to protect herself and invigorate her life with an imagined, long-lost, eternally present family through art. Though not particularly mindful of the differences between the Dutch Golden Age, the Impressionists, or the École de Paris, Flack would eventually become quite interested in her status as the likely first Photorealist, projecting photographs onto canvas to aid in making her paintings.

In her youth, drawing with preternatural skill in black charcoal with no photographic source material, Flack successfully competed in a rigorous live audition for admission to the renowned public High School of Music & Art in Manhattan—from which she graduated with an award for being the most outstanding visual artist. Despite her mother’s repetitive and unwavering warning that “too much education spoils a girl’s chance of getting married,” Flack proceeded to apply to the tuition-free art school Cooper Union, where she was selected as one of ninety students among 3,000 applicants.

Flack devoted considerable attention to her own abstract oil-on-canvas paintings. “I had been moved to explore the incredible variety of differences between flake, ivory, lead, and titanium white, as well as ivory, mars, and lamp black. I infused them with color by mixing blue-whites, yellow-whites, blue-blacks, brown-blacks, and so on, so that while the painting was officially black and white, it was rich and rife with subtle overtones of color,” she writes.

“I never wore color when I painted,” Flack explains of her careful process. “It interfered. I wore denim jeans, a black sweatshirt, no lipstick, no makeup. My hair had to be pinned back, and even my underwear couldn’t have any color. No ego. Nothing to get in the way of clear vision.” Regardless of what Flack wore when painting, her self-presentation made an impression in the art world. Pollock once suggested that they go to either her or his apartment to fuck. Some years later, Andy Warhol was drawn to the large initial “A” on a ring that Flack wore. He asked her if he could have the ring. Unlike most women, Flack had the uncommon sense to say no to both men.

In one notable sequence, Flack recounts her brother Milt’s return from WWII in 1945, bringing with him a small black portfolio containing watercolor paintings by Adolf Hitler. Milt had extracted them from Hitler’s Bavarian retreat, Eagle’s Nest, which he had to leave quickly as the Nazis lost ground. Despite her revulsion at handling Hitler’s creations, Flack nonetheless admired his skillful technique, recalling nineteenth-century academic artists whose work was shunned by modernism of all sorts—specifically Gérôme and Bouguereau—and felt herself “transformed.” “How could this fiendish criminal orchestrate the murder of millions of innocent people and yet draw so well? I’m Jewish, and had my parents not immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe, they certainly would have perished in Hitler’s ‘Final Solution.’”

Her life was changed abruptly not only by Hitler’s paintings, but by meeting her first husband, Frank Levy, a former Music & Art student. According to Flack, Levy was “the star cellist in Music & Art’s string quartet.” Frank asked Audrey to his apartment for an evening of chamber music. Enthralled by Frank’s cultural inclinations his family’s intellectual milieu, she went on a second date, to which Frank wore Sigmund Freud’s overcoat and button-fly trousers. They courted for just two months and then married. Shortly thereafter, Flack threw these Freudian garments into the garbage, literally trashing the vestments of the psychologist who deemed women passive, submissive, and inevitably inferior to men. The gesture ranks as one of the wisest things she ever did.

Throughout her career, Flack continued to be surprised by the scarcity of women in the art world. Even as she began to show her much-lauded Photorealist paintings in the 1960s, she remarked on the sexist situation in the art world, as if it were a novel revelation: “I saw myself for the first time as the only woman in a group of male artists including Chuck Close, Robert Bechtle, Richard Estes, and a dozen other artists.” In With Darkness Came Stars, Flack is at her absolute best as an artist—and writer—when she stops trying to position herself within an art-historical context, or a continuum of anything “historical,” and forcefully and directly expresses herself.