Eric Fischl deems that “ambiguity is the essential quality of art,” as he has often declared, and he has succeeded in achieving this potent goal in his most recent work, the “Hotel Series,” from 2023 to 2024. Unfettered from the artist’s cynical scrutiny of American suburban decadence prevalent in earlier works, these recent, large-scale compositions take the edge off his familiar, voyeuristic approach. Instead, Fischl’s visual observations provide the viewer with suggestive glimpses that provoke the imagination to stray impulsively from the banal routines of quotidian life in multifarious ways. Deftly eschewing sentimentality, these incongruous scenes elicit conflicting emotional states that involve intimacy versus anonymity; trepidation versus anticipation; desire versus solitude; respite versus refuge; transience versus permanence; and so on—sumptuously fueled by the technical virtuosity and orchestrations of color for which Fischl is well known. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, the New-York based artist played a key part in the revival of figurative painting enriching his compositions with contemporary relevance by means of subtle sociopolitical commentary.

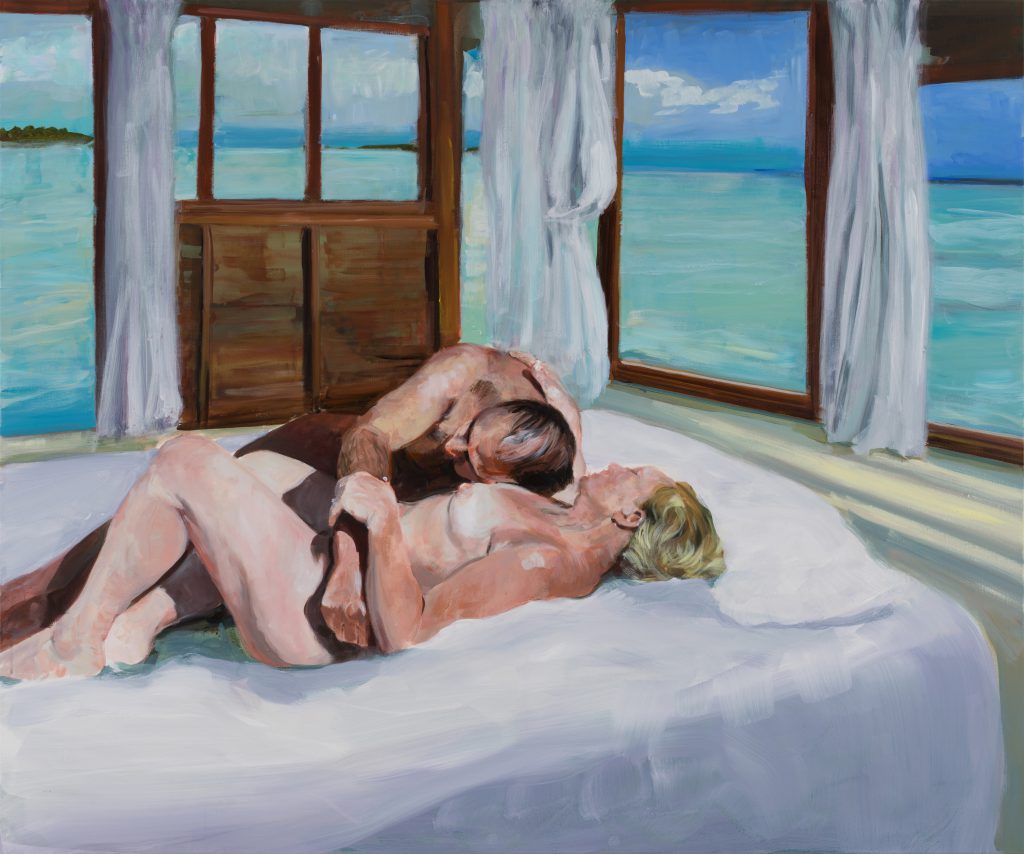

In Last Days at Tender Cove (2024), for example, a naked couple lies intertwined on a bed. Although seemingly in repose, the man tenderly lays his head on the chest of his female partner as his arm frantically clings on to her. In the aftermath of rapture, the moment is encapsulated by the enduring, yet indifferent, mesmerizing beauty of a sea’s turquoise-green surface framed by the panoramic windows surrounding their room. In another composition, sitting on the edge of a bed, a woman with a towel wrapped around her head, clasps a pillow to cover her naked body. Two spaniels remain on the bed for the time being as her only companions. Her back to us, she twists halfway around, gazing toward the door—and the viewer—with a forlornness for having perhaps been left behind or, alternatively, with the anticipation of a return. The poignancy of the scene is amplified by drifts of translucent amethyst brushstrokes on the white sheets, suggestive of creases and bodily imprints, bordered by the velvety violet opaqueness of the blanket that cloaks the rest of the bed in darkness.

In contrast, King’s Highway: Killing Time (2024), strikes a more ominous, less personal note—in a reflection of our precarious times. In this work, our focus shifts from a man reclining on his hotel bed, strumming a guitar, to a window from which one sees a night view of Seattle’s Space Needle. At first glance, the scene conveys a relaxing vibe, until one deciphers an AK47 propped up against a chair in the background. All this disquietude gets attenuated by the bewildering, fluid configurations of random splatters and patches of bright yellow paint on the mottled surface of the dark grey carpeting on the floor. Suggestive of flickering ambient light, combined with passages of vigorous sweeping brushstrokes and medleys of wispy lines, these quasi-cinematic passages conjure ghostly silhouettes and faint delineations of visages that lend even more uncertainty to the situation at hand.

As Fischl navigates into these new visceral territories with a multiplicity of narrative possibilities, viewers are draw in, taunted, in one way or another with scenarios that for the most part are credible. As such, despite ourselves, we become complicit participants, uncomfortably, wishfully, or reflectively. At times, we even feel empathy for his subjects—imagine that.