I.

Between visiting the five-thousand-year-old pyramids of Giza and heading south to the Valley of the Kings, where four thousand years ago ancient Egyptians began to cut tombs for their pharaohs, I toured Zamalek, a Manhattan-shaped island in the Nile River near Cairo. Thrumming with international students and filled with posh cafes, Zamalek is also the bedrock of the city’s—and the country’s—contemporary art scene, with tens of galleries dotting the tree-lined streets. While there, I visited several shows, the first two of which were being held contemporaneously at Ubuntu Gallery.

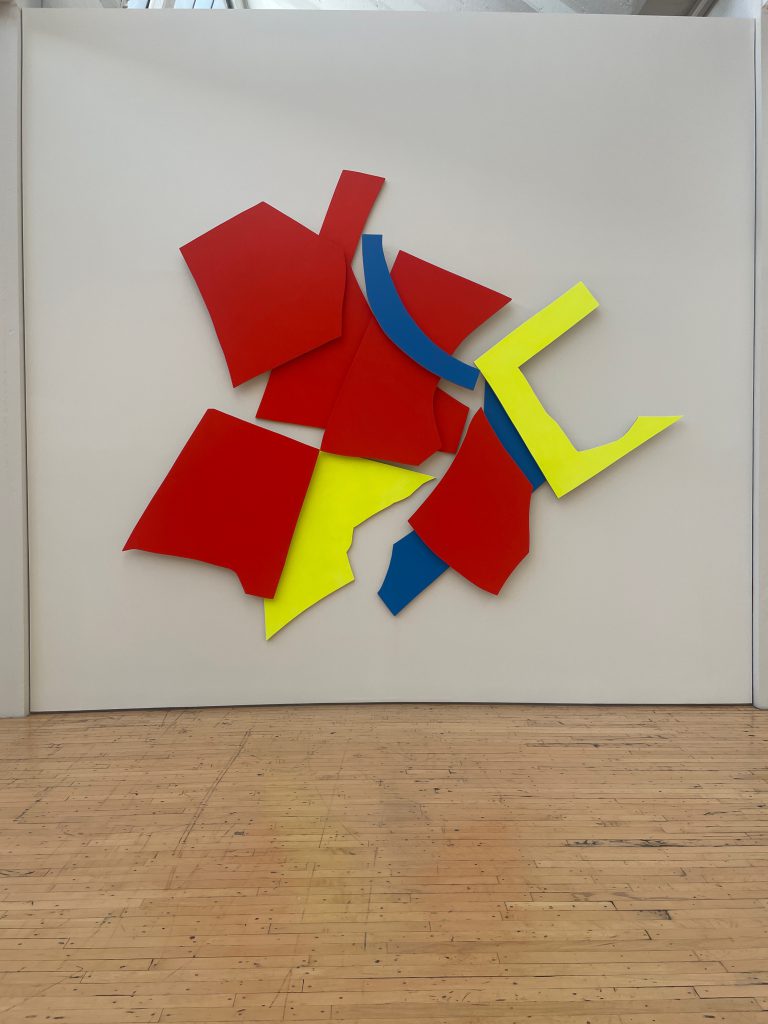

One enters Ubuntu by way of a garden-level gallery: installed there was Mind the Gap, a collection of colorful acrylic-and-plywood wall sculptures by architect and artist Eman Hussein (b. Cairo, 1986). The sculptures feature imagined geographic shapes, evoking continents that have been dislodged from the surface of the earth, and are rendered in rich, marbled colors. All works are composed of multiple—two or three—panels, which sit atop one another to create cartographic wall sculptures more fantastical than, but in the vein of, those by the German minimalist Imi Knoebel and the Arte Povera exponent Luciano Fabro. Hussein’s sculptures, which are untitled, function both individually and as a collective entity, addressing the simultaneous fragmentation and cohesion of the earth and its inhabitants.

Ubuntu’s second exhibition, upstairs, was a Azahiri, a show of paintings by Haytham Abdelhafeez, an artist from central Egypt who now resides in Cairo. Many of Abdelhafeez’s large, vibrant compositions employ acrylic, oil pastel, and charcoal to create impressionistic still-lifes of towering floral arrangements, into which figures sometimes wander, or at whose beautiful peripheries, they rest.

Photo by Nina Rosborough.

At another nearby gallery, Safar Khan, I encountered the work of the late artist Ibrahim Abd Elmalak (1944–2011), who is especially well known in Egypt for his wood and metal sculptures, and whose son, the painter Karim Abd Elmalak, is now an artist-in-residence at the gallery. On view, Years of Love, was a compilation of shows that the elder Abd Elmalak had presented during his lifetime, and featured drawings, paintings, and sculptures.

Inflecting abstract shapes with the spiritual and mythological, Elmalak’s sculptures largely render or reference the female form. However, these works are more embellished than the smooth, round figures favored by Egyptian modernists—like the sculptor Mahmoud Mokhtar (1891–1934) and the painter Hussein Bicar (1913–2002)—who inspired him. The intricacies of Elmalak’s work—often imprinted and scalloped and otherwise heavily molded before being cast—suffuse them with movement, lending them an energy that seems capable of liberating itself from the plinth and possibly, even, from the container of the sculptures.

II.

I am grateful to have been made aware of the existence of the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center, a small museum that doubles as a commercial gallery on the road between Giza and Cairo. The museum, which is set back and surrounded by tranquil gardens replete with hibiscus, is difficult to find, but contains some of the most stunning and intricate tapestries I have ever seen. Wissa Wassef (1911–74), a Coptic architect, potter, weaver, designer, and professor at Cairo’s College of Fine Arts, established the Center in the mid-twentieth century as a sort of social and creative experiment: he set up a workshop where he encouraged local children to learn the art of hand-weaving, without the aid of sketches or designs. A number of the children that Wissa Wassef and his wife Sophie mentored grew to be professional weavers who relied on expressionistic instinct in lieu of plotted artistry. Some of those weavers are still affiliated with the Center today, where their works—as well as those by younger artists—are displayed.

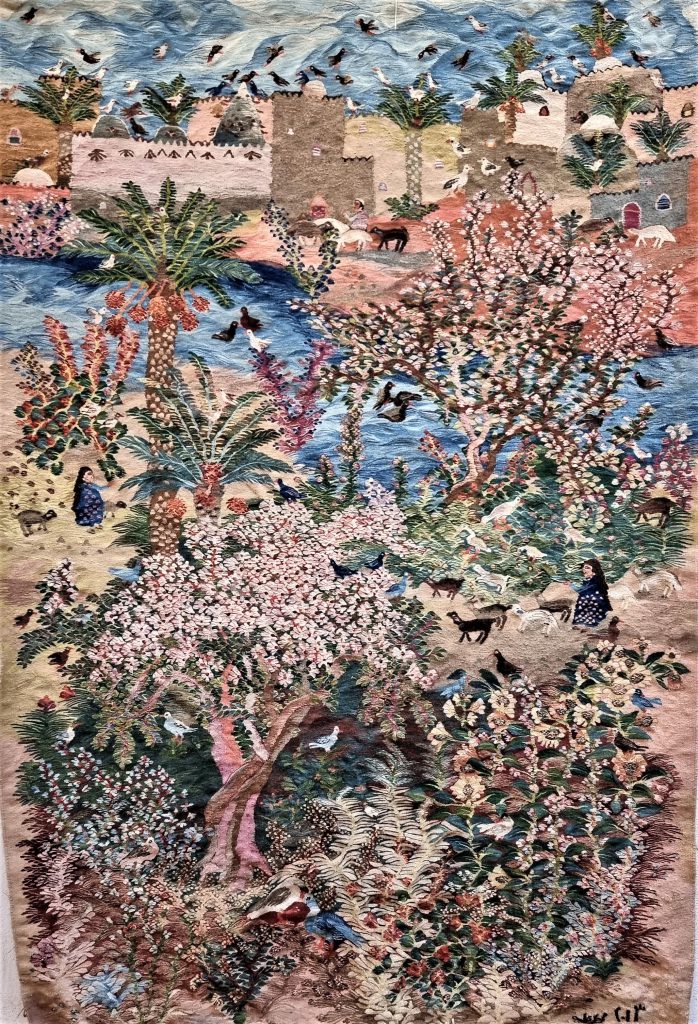

Photo courtesy of Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center, Cairo.

The tapestries vary between the truly representational and the nearly abstract. In Tree & Pond (2013), a very large vertical work by Lotfeya Shaban, flowering trees resembling the ancient Egyptian Tree of Life—a popular motif in traditional art—provide havens for birds and shade for the women and animals who work under them in the foreground. The Nile, stitched in cerulean blue, runs across the middle ground—on its other side are rural structures, both domestic and communal, outside of which more animals roam; the natural world is both counterposed and in harmony with the man-made one.

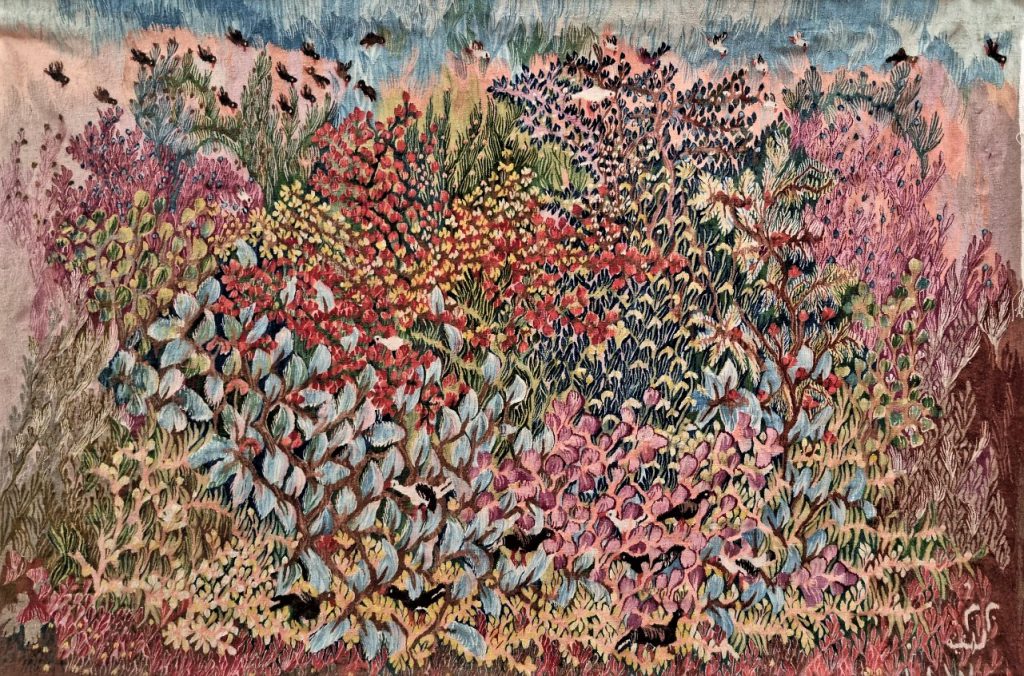

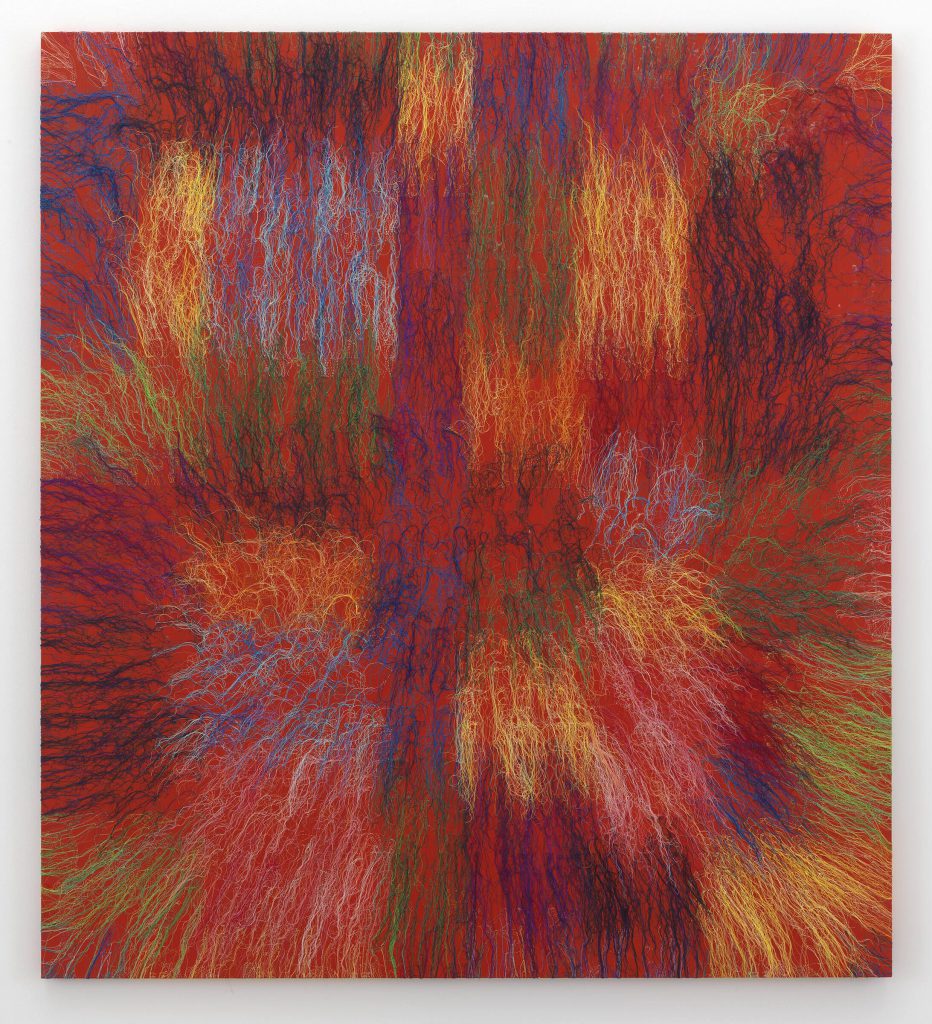

In contrast, Flowers (2020), a horizontal tapestry, also by Shaban, presents an impressionistic mélange of flora that grows from or toward no fixed point, and which reminded me of works like Red Bang (2014), by the New York-based, Cairo-born artist Ghada Amer, who subversively disorders the structure and motifs we tend to associate with embroidery. Rather than depict reality, Shaban’s more abstract work becomes a celebration of color and—in tribute to Wissa Wassef—of the power of unfettered creativity.

80 x 72 in. (203 x 183 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen.

© Ghada Amer. Photo credit: Brian Buckley

Editor’s note: Shaban’s Tree & Pond, as well as several other of her tapestries, were displayed at Ubuntu’s The School of Instinctive Creativity, an exhibition of works by Wissa Wassef artists in June.

III.

Because a great deal of Egyptian art made in ancient times is now visible only outside of Egypt—though the Egyptian Museum in Cairo has the single greatest collection of Egyptian antiquities in terms of volume, the combined volume of artifacts held abroad (in the British Museum, the Louvre, the Brooklyn Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example) far exceeds the domestic quotient—I extended a layover in London in order to begin to fill in the gaps. Doing so also allowed me a small continuation of my foray into and education about Egypt’s corpus of modern and contemporary art, much of which seems to have, like its ancient forebears, left the country.

At the Tate Modern, I visited Surrealism Beyond Borders, a phenomenal show that originated in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and which includes work by Egyptian artists—the exhibition is in London through August 29th. The curation organizes Surrealism as a movement into geographical loci. Cairo in the early 20th century was one of these hubs. The brand of Surrealism that flourished there was particularly macabre, taking up a palette reminiscent of dark Renaissance masterpieces like Caravaggio’s The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608) and the woman painter Artemisia Gentileschi’s proto-feminist work Judith Slaying Holofernes (c. 1612–13).

Such is demonstrated by Young Girl and the Monster (1942), by the modern feminist Inji Efflatoun, in which the disembodied head of the titular girl lolls in the bottom right corner of the canvas, blood streaming from her mouth, while the broken head of a man—presumably the monster—affixes its own mouth to her face. The rest of the painting is occupied by a fiery, apocalyptic landscape, through which icy-blue bolts occasionally streak. The work indicts Egyptian society—then victim to intermittent British occupation—for its mistreatment of women both as an objective protest of such inequity and as an implicit portrayal of Egypt’s enfeebled state.

Nearby hangs an untitled 1940 work on cardboard by Fouad Kamel (1919–73), a member of the al-Fann wa-I-Hurriyya/Art et Liberté (Art and Liberty) group of artists and writers. Under the bilingual umbrella of “free art,” the collective adopted the subversive tenets—creative submission to the unconscious, a related aversion to establishing boundaries between reality and unreality—set forth by André Breton in his 1920s Manifesto of Surrealism. In his composition, Kamel, like Efflatoun, deploys the female form to relay incisive social commentary. Here, a nude female figure stands thigh-deep in a crimson swamp. Her arms are either missing or tucked behind her back, and her head is cocked submissively down and to the side. She is robustly muscled and Kamel plays with perspective in a way that makes it unclear whether she is or only appears to be enormous, and godly in that enormity.

I left Egypt here, by way of its art, both unsettled and encouraged by Kamel’s painting and the artists in the Surrealism show. I was unsettled not only by the works’ disturbing contents, and the affect such contents transmitted, but also by the prospect of how our conception of the evolution of modern art might have differed had Egyptian Surrealism—and other arms of modern art—been admitted to the canon earlier on. I was encouraged by the fact, however belated, of that admission, and by Cairo’s commitment to cultivating the legacies of its 20th-century artists and the future of its contemporary generations.

Thanks.