Helen Pashgian’s immersive retrospective at SITE Santa Fe brings the viewer into a semantic space that toggles with the space of pure perception. The viewer sees and then begins to think and question: What is one looking at? Where does the object begin in a controlled environment and where does it end? What is meant by a material presence, and what is pure sensation? And, hopefully, the viewer will arrive at an expanded conceptual/perceptual space rich with elusive shades of meaning. Being in the midst of her work, it becomes easier to talk around than talk about her art as Pashgian seeks to understand the materiality and immateriality of light—light is after all both a particle and a wave. The artist explores light as an essential property of existence and the medium of light as something to be investigated and translated into objects, experiences, phenomena. If extreme subtlety of effects is Pashgian’s aim, the viewer has to engage with her work well beyond a ten-second glance in order to begin to comprehend the various ways the artist wrangles with the idea of the subtle and, in the last analysis, themetaphysical nature of her objects and installations.

When I say it’s easier to talk around Pashgian’s work then find a pathway into interpretation, I’m referring to the way reviewers have dwelled on the artist’s early association with the Light and Space Movement out of Southern California in the 1960s and ‘70s. Yes, there is that fact to consider, but the truth is Pashgian became, for various reasons, underrecognized in subsequent decades, just as the Light and Space artist Mary Course was underrecognized—and who, like Pashgian, has resurfaced in the new millennium to international acclaim. One could blame their quasi-career eclipses, as it were, to the power of the male ego in the ’70s expressed in a generally sexist climate. This is especially true of Pashgian who was, and still is, beautiful, elegant, and independent, and as one of the Light and Space artists commented, she not only had her beauty working against her, she also “came from a family of means.” That said, even if Pashgian fell off the artworld radar for a while, she never stopped her experimentation with new methods and materials to express light’s range of phenomena.

Besides Pashgian’s exhibition at SITE Santa Fe, which runs through March 27, the artist’s work was also shown at Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York—Helen Pashgian: Spheres and Lenses—through January 15 (https://www.lehmannmaupin.com). At SITE, the artist had access to a series of expansive spaces to showcase her work—work that is at once alluring and elusive as if from some realm that is both primordial and futuristic. What is more primal than a beam, a blush, or a reflection of light? Yet, Pashgian had help creating the ineffable effects of her art through the technological and the electrical. You could say that the latter two domains are a very important part of Pashgian’s sensitive dependence on initial conditions—the technology inherent in working with new materials like cast acrylic and polyester resins, and the controllable nature of electrical currents essential in the lighting of her pieces in their respective environments. What she achieves in her sculptures and installations (all the works are untitled) is not for the impatient. The viewer needs to sit or stand still, let their eyes adjust to extremely subtle phenomena, let expectations drop to the floor, and then let them rise to the occasion. Rise, expand, and become rapt in the experience of an artist’s unique vision of a material object—like a polyurethane disc— seemingly in the process of dematerialization.

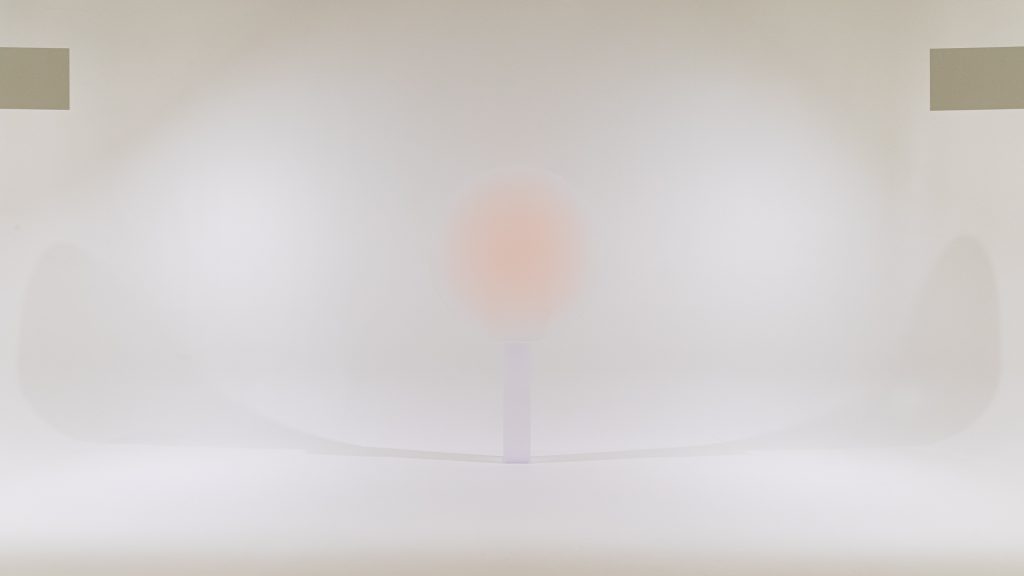

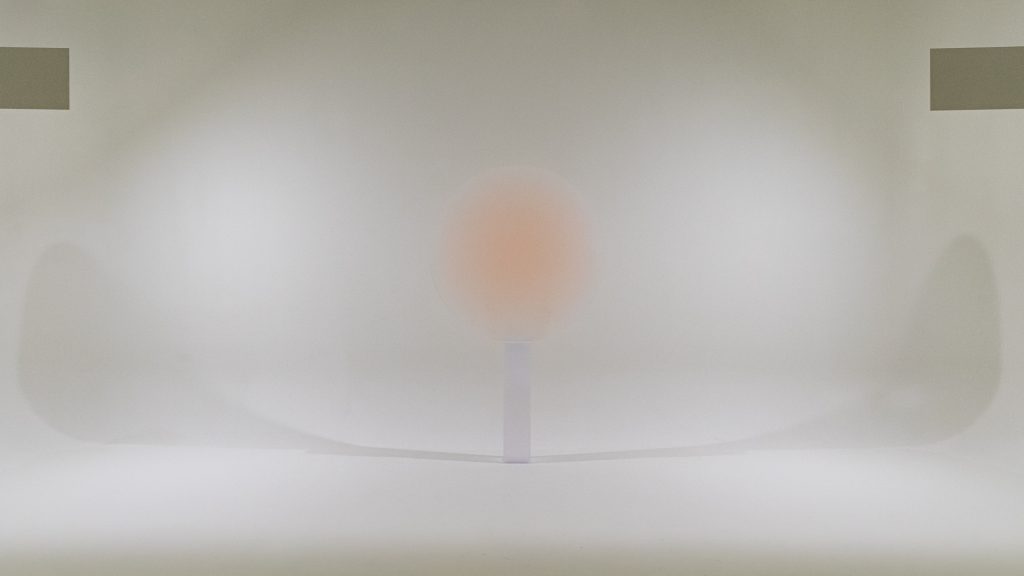

Presences is the title of Pashgian’s SITE exhibition and, as the title suggests, the concept of moving a material object into the realm of the metaphysical—the zone of pure presence—is at the heart of Pashgian’s evolution as an artist. And at SITE, this quest has been realized with exquisite and singular power especially in one particular installation, Untitled (2021). This work features a large pink disc in a lofty space whose architecture has been altered somewhat, and which utilizes a system of variable lighting. The disc is five feet in diameter and is positioned on a transparent plastic stand. Pashgian’s polyurethane discs, or lenses as they are also called, seem more to be floating in space than attached to a physical pedestal, and the illusion of hovering in a refined and speculative atmosphere is particularly true of this work.

Walking into this pristine, chalk-white environment, the right and left-hand walls are curved at the bottom; gone are the right angles as wall meets floor. The lighting is already dimmed so the viewer goes into a half light and it’s only when a person gets too close to one of the side walls that the curve appears out of the misty light and the effect is one of immediate disorientation, as if one is about to fall into the curve. Near the front wall, where the disc is placed, the pale pink object changes continually in a five-minute cycle of variable light that morphs from a semi-brightness to an intense dusk. The disc is there and then it barely exists as a cloud seems to descend on the object rendering it to a liminal and gorgeous presence. As the cycle repeats, every appearance and disappearance of the disc becomes more breathtaking, more unreachable in physical terms, and it mirrors light’s inherent evanescence. There is the sensation of traveling into a limbo state where the human body is about to undergo a reincarnation into a uniquely altered state.

The light in this space—as it makes a transition as if from the first blush of dawn to the descending darkness of evening, and then back again—casts a shadow on the floor under the disc. The shadow reminded me of an ancient Egyptian boat—thin on the bottom and curved upward on either end—the kind of boat that carried the souls of the dead into the underworld in Egyptian mythology. For me, this was not a stretch of the imagination to think of this installation as the site of the psyche’s reincarnation. And what is so strange about that? Pashgian’s work makes a serious demand on our attention—it asks us to leave the day world behind and submit to a new potential, a new level of energy exchange, so as to be momentarily born again into the artist’s vision. Isn’t this what all art asks of us? After sitting for a long time in this space, I walked across the room and got closer to the disc and it was as if the ambient light had become pulverized, become microscopically granular; it had the quality of a fine powdery substance—the presence of light appearing to itself.

If the room of the pink disc was a journey into limbo, the installation with twelve translucent acrylic columns lit from within was like being in a tomb with other worldly beings. Each column was fabricated of two ovals and embedded inside each column was what I called a light element—each column possessing a different acrylic object, or material configuration, of a certain color and shape. This room, too, was on a cycle of changing light, in this case from dusk to dark. And as ravishingly beautiful as the columns were—as intriguing and varied were the shapes inside them—it felt as if one had indeed entered a space of ghostly presences—not guiding us to a specific destination, but leading us in a closed loop around the limits of our attention. If the feeling in that room was uncanny, and even a little spooky, the stakes were high in the realm of artistic intention. This installation, in particular, rewards the viewer with glimpses of the artist’s ability to turn blunt materials into an extraordinary set of phenomena—sublime, transcendent, and reflective of light’s dual nature—light as both a particle and a wave. Nothing is more challenging for an artist than to make manifest a substance more ephemeral than an artist’s vision. When that vision also rests on a fulcrum of ephemerality—a double burden when it involves the mutable nature of light—then the work of the artist must embrace a path of rigorous practice and inventive procedures. At this thorny intersection is where the viewer takes control and seeing is believing.