The Museum of Modern’s Art’s survey of Sophie Taueber-Arp, Living Abstraction, and the oeuvre it presents, is mesmerizing, so much so that I have been back to immerse myself in the world of Taeuber-Arp more than once. With the exception of certain problematic contextual gaps, I found the exhibition, like the work, to be simultaneously playful and intuitive, exemplary of a unique abstraction that settles within, rather than upends, the regular course of life.

Born in Switzerland in 1889, Sophie Taeuber studied both applied and fine art in Germany before returning to her homeland in the midst of WWI, and meeting Jean Arp at a 1915 exhibition. The two would marry, and Taeuber-Arp would, as others have pointed out, join the ranks of other wives of renowned male artists who would wait decades—many until after their deaths—for their independent moments in the spotlight. Such resuscitations are central to the themes of recent shows of nonrepresentational art, including Labyrinth of Forms: Women and Abstraction, 1930–1950 at the Whitney, and Women in Abstraction, which appeared this past summer at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Living Abstraction posits that, besides or related to her femaleness, Taueber-Arp’s status as an artisan is art history’s reason for largely overlooking her: “Gender discrimination is…only one of the reasons Sophie Taeuber-Arp remains far from a household name. Another significant factor has to do with the varied nature of her artistic practice,” writes MoMA senior curator Anne Umland for the show’s catalogue.

at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar.

The show’s curation, led by Umland, boldly emphasizes this artisanship, positioning Taeuber-Arp as a polymath unafraid to allow her varied practices to commingle. Formally, the exhibition evinces such productive cross-contamination, as artists more concerned with methodical purity might have construed it. Disavowing the bourgeois pretensions of other art, Taeuber-Arp’s fellow (mostly male) Dadaists privileged absurdity above all else. Taeuber-Arp, on the other hand, embraced the useful. The first gallery of the exhibition is dedicated to such utility. Snippets of textiles are framed and hung beside the drawings and studies that gave way to them; handbags and necklaces are placed on pedestals inches from an abstract sculpture used by Taeuber-Arp’s sister as a powder box. Other artifacts, like the indisputably architectonic Design for an Embroidery (c. 1915–1923) foreshadow future avenues Taeuber-Arp explored.

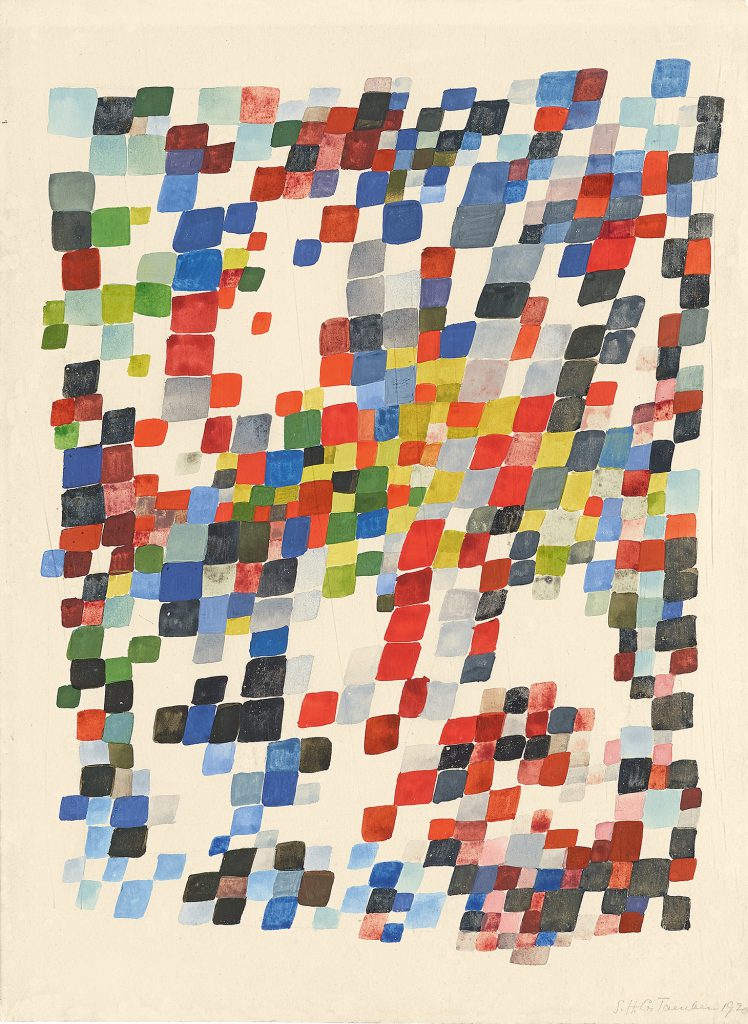

Appended to the primary flow of the exhibition is a secondary gallery with dark grey walls. Here live the piquant marionettes Taeuber-Arp created for her 1918 puppet show King Stag. These are composed of familiar geometries—the limbs of the eponymous King appear like three-dimensional realizations of triangles included in earlier works, while his crown recalls the amphora shape that fascinated Taeuber-Arp throughout her working life. A video of the 1918 performance plays in the gallery, which functions like a fantastic, shadowy chamber in the artist’s mind: the place where Dada whimsy flourished in tandem with industry. Such synchronicity is critical. Exiting this gallery and rejoining the exhibition’s main space, one does not so much part with the pleasantly offbeat works contained in the former, but instead apprehends how they resurface in and aid in the evolution of Taeuber-Arp’s overall practice. A gouache on paper entitled Composition of Quadrangular, Polychrome, Dense Strokes (1920) is a looser version of her earlier textile plans. Moving along, iterations literally unspool, becoming less and less plotted, until, in Quadrangular Strokes Evoking Group of Figures (1920), human forms emerge as Taeuber-Arp anthropomorphizes geometry, much in the way she did to create the marionettes.

It is impossible for me to commend the marionettes, as well as the 1920s textiles housed in the succeeding gallery, without also addressing the fact that cross-cultural context is conspicuously and concerningly missing from the exhibition as a whole. That the marionettes, as well as Tauber-Arp’s beguiling “Dada-heads”—the cranial sculptures she made at various instances throughout her career—resemble African masks and other handicrafts is undeniable. Furthermore, the troubling art historical connection between Dada and Africa has already been pointed out, making its exclusion from Living Abstraction doubly regrettable from a curatorial standpoint. As regards the textiles, similar inquiry into what was borrowed from the indigenous cultures of the American Southwest is wanting, and it is unnerving to take in the desert-shades of a work like Composition (tapestry) (mid-1920s)—which the New York Times critic Jason Farago also highlighted—to seek context from the wall text, and to be unable to find it.

Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, France.

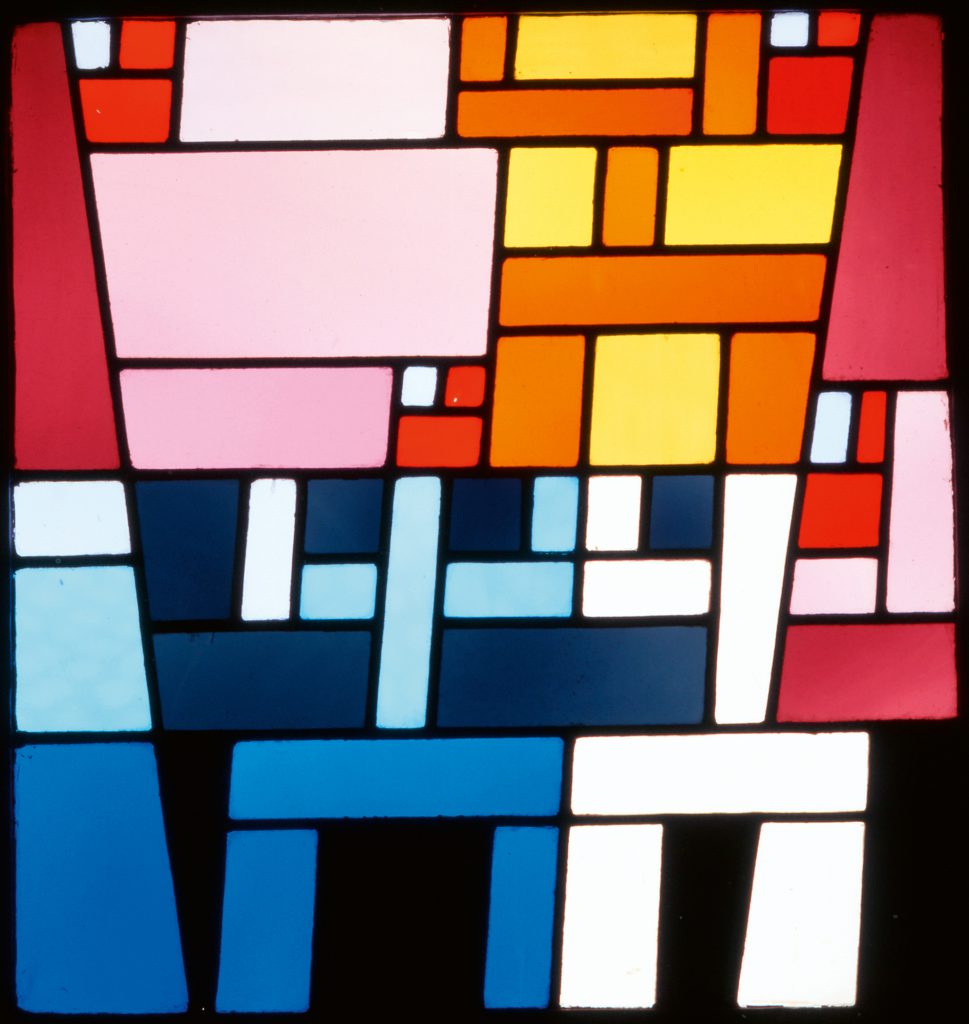

An irrepressible sadness arises in the second half of the exhibition with the knowledge that Taeuber-Arp died of carbon monoxide poisoning at fifty-four after lighting a fire in a woodstove in the home of fellow Swiss designer Max Bill, and neglecting to open the flue. In the 1930s and early ‘40s, she received a number of prestigious architectural commissions, the renderings for which demonstrate her expansive imagination. Her plans for the Strasbourg cultural center L’Aubette, for instance, summon the intricacies of her textile work and of the romantic schematizations of cityscapes she conducted when she traveled. Her blueprints for Paris’ Galerie Goemans, where works by her husband as well as Tanguy and Magritte would be shown, depict stylized columns suggestive of the singular approach to modernism she was beginning to develop. A series of backlit stained-glass windows, designed for the apartment of the art collector André Horn, also illuminate this gallery, and functionally reimagine earlier geometric designs.

The moment was similarly propitious for Taeuber-Arp’s fine art. Whereas, in the 1910’s and early 20’s she had toyed with the boundaries between abstraction and representation, in the 1930’s she breaks any remaining allegiance to figuration into constituent elements. Take Café (1928), for example. Here, rudimentary characters interact in a field whose depth is signified only by changes in color and opacity. A vital red establishes a foreground in which a duo of figures is attended by a waiter. In the muted gray background, another pair throws their arms up. From this moment in the retrospective on, Taeuber-Arp forces the substance of her artistic compositions into a machine of figurative devolution. The human-esque forms in Café, which could have descended from those of Quadrangular Strokes Evoking Group of Figures, are gradually disembodied, becoming a language of parts.

The result of such artistic austerity is a proliferation of non-objective works like Schematic Composition with Multiple Circles and Rectangles on Black Ground (1930), which—except for a set of bucolic landscapes from 1942—make up the remainder of the exhibition. War was impending, and then arrived, with all its horrors. Though she could not have anticipated her own terrible mid-war fate, the last chapter of Taeuber-Arp’s career appears as an attempt to untangle the very fabric of life. This is what I gleaned, at least, from her otherwise enigmatic drawings from this period, in which forms are largely reduced to colored lines that intersect one another but seem to proceed according only to themselves. Yet works like Geometric and Undulating, Lines (1941) do not actually depart from the logic inherent in design, in putting together an object like a tapestry. Rather, they logically undo it, leaving only disconnected lines.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction is on view at MoMA through March 12, 2022. Prior to its MoMA presentation, the exhibition was shown at the Kunstmuseum Basel (March 19–June 20, 2021) and at Tate Modern in London (July 13–October 17, 2021).