Pace Gallery, New York ©️ Julian Schnabel

Highlights of New York Contemporary Art Galleries at the Shutdown

As Covid-19 spread, with social distancing restrictions in place and most workplaces shuttered in response, New York City’s art galleries and museums entered lock-down mode in mid-March. As of mid-May, there were still no reopening plans in sight. The art world has practically ground to a halt, retreating to the illusionary effects of cyberspace, social media, or furtive drive-by exhibitions to simulate a creative environment that is, sadly, a mere ghost of its former self. The situation’s toll on artists, the art community, and cultural economy has yet to be determined comprehensively, but like the rest of the country’s condition in the wake of the pandemic and financial fallout, it is likely to be dire if not devastating.

At least for the moment, firsthand experience of artworks and art exhibitions have become precious memories that need to be preserved. Below are brief comments about some of the most memorable exhibitions I experienced in person just before the gallery shutdowns. These are gallery shows that on some level moved me intellectually, personally, and emotionally. Several of them constitute remarkable achievements by artists relatively new to the New York art scene, while others are key exhibitions by midcareer artists, or milestone presentations by art-world veterans, including a number of the most influential artists of our time. Some of the galleries mentioned here promise to keep these exhibitions on hold, and to reopen them to the public as soon as social distancing and other restrictions of movement due to the pandemic are relaxed.

.

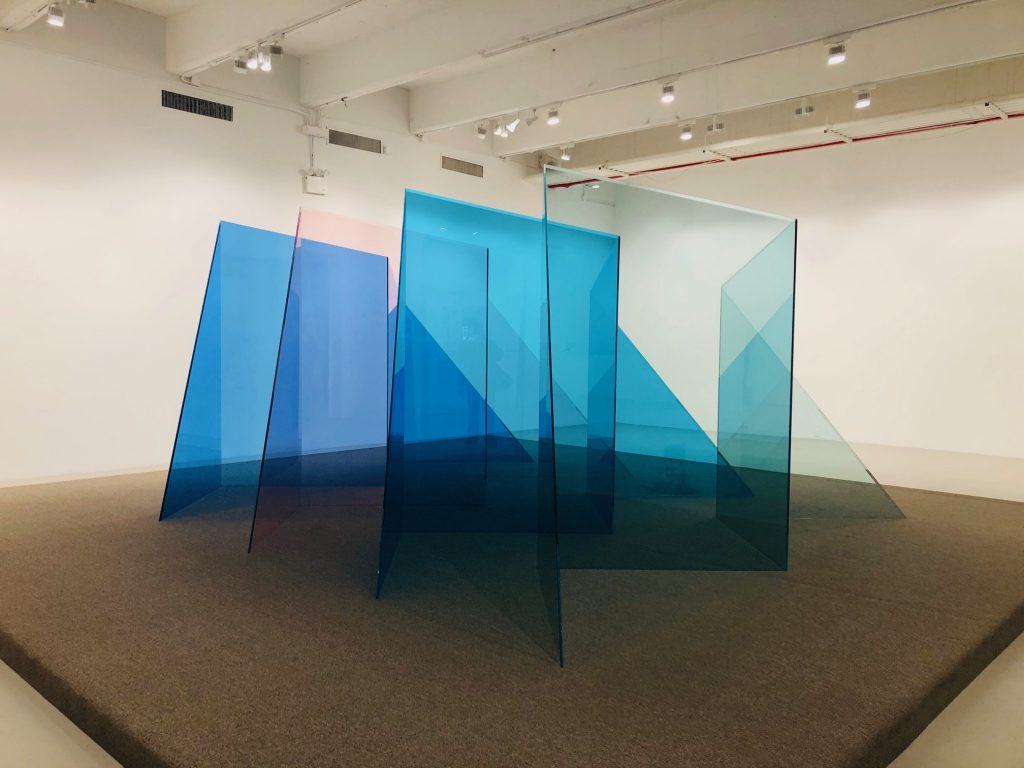

- Larry Bell at Hauser & Wirth

In this exhibition, Larry Bell: Still Standing, the Chicago-born, Los Angeles- and New Mexico-based artist proves that not only is he still standing, he is doing the best work of his long career. Well known since the early 1970s for his translucent, coated-glass cubes; “nesting box” works; austere Minimalist “standing walls,” installations of large-scale glass panels, Bell continues to explore in this show the properties of light–reflection, refraction, and shadows. Using related forms, formats, and procedures, Bell achieves in the recent series ever greater complexity and novel spatial relationships that constantly challenge viewers’ means of perception.

In this stunning show, Bell debuts a new series of “Iceberg” monumental sculptures and smaller studies. Perfectly situated in their respective gallery spaces on the ground floor, as if they were site-specific works, the two largest “Icebergs” feature angular glass panels looming nearly eight feet tall and fourteen-feet across. In Iceberg, 2019, quietly shifting tones of gray, white, and pale green–realized with thick panes of clear glass, chemically coated in shades with trademark names, such as True Fog, and True Sea Salt–emerge and recede as one moves around the sculpture. The timeless, meditative quality of the work, and the consideration of its cool infinity, recall a study of the sublime, such as Caspar David Friedrich’s 1823-24 painting, The Sea of Ice.

Even more romantic in temperament, the majestic Iceberg, 2020, features an arrangement of glass panels laminated in shades called Spa, Blush, Cornflower Blue, and Lagoon. The sensual tones of the work and the warm glow that envelopes gallery-goers within its physical purview, surely offers the hopeful promise of spring, as well a unique and indelible experience of art in its purist and most adventurous form. This is an experience that cannot be conveyed digitally.

2. Julian Schnabel at Pace

Julian Schnabel’s exhibition of recent abstractions, The Patch of Blue the Prisoner Calls the Sky, is at once romantic, cathartic, and profound. Although an exhibition of paintings, these are not precisely two-dimensional paintings, and the show requires the viewer’s physical presence in order for the works to attain their full visceral impact. With the huge scale of the compositions, the spatial shifts of the shaped canvases, as well as color and the dense and intense textural nuances of the painterly surfaces, Schnabel addresses the observer directly, like the protagonist in a grand opera.

Since the early 1980s, Julian Schnabel has been admired by many and disparaged by some for reiterating or reincarnating a kind of heroic artistic persona not seen since the American Abstract Expressionist movement in the 1950s. At that time, mural-scale compositions by outsize personalities like Pollock, de Kooning, and Kline captivated the art world and enthralled art audiences. In between successful forays into film—most recently with the Van Gogh-inspired film, At Eternity’s Gate, starring Willem Dafoe as Vincent—Schnabel perennially returns to the art world with always thought-provoking and dazzling works like those on view here, which convey a sense of raw emotion.

I agree with James Nares, the artist and author of the show’s catalogue essay, who writes of Schnabel’s generosity of spirit evident in these works. “A true and duly expressed feeling is not an act of self-indulgence, but to my mind one of supreme generosity, often great courage, even self-effacement.” The show’s title, “The Patch of Blue the Prisoner Calls the Sky,” was borrowed in part from an Oscar Wilde poem, and also suggests to me A Patch of Blue, the 1965 film starring Sidney Poitier, based on Elizabeth Kata’s 1961 novel about an interracial couple’s anguished struggle with bigotry and oppression.

Painted on cotton “lonas,” or tarps, found fabric the artist acquired in Mexico, typically used to shade food vendors and market stalls, the largest works are stretched irregularly, with elongated points of one of the lower corners, mimicking the billowing canvas of a sailboat or of a market stall shade on a windy day. Spanning nearly 15 feet long and 11 feet high, Lagunillas II, one of the riveting works on view, features a drab gray background with a network of brilliant red-orange brushstrokes that emanate from the lower left, elongated corner of the canvas. An intense and nearly explosive energy seems to be concentrated in that peculiar place. The more conventionally stretched canvases contain rich impasto surfaces packed with frantic and incisive brushstrokes. The markings suggest furtive movement within ambiguous spaces that are neither interior nor exterior, but physiological in nature.

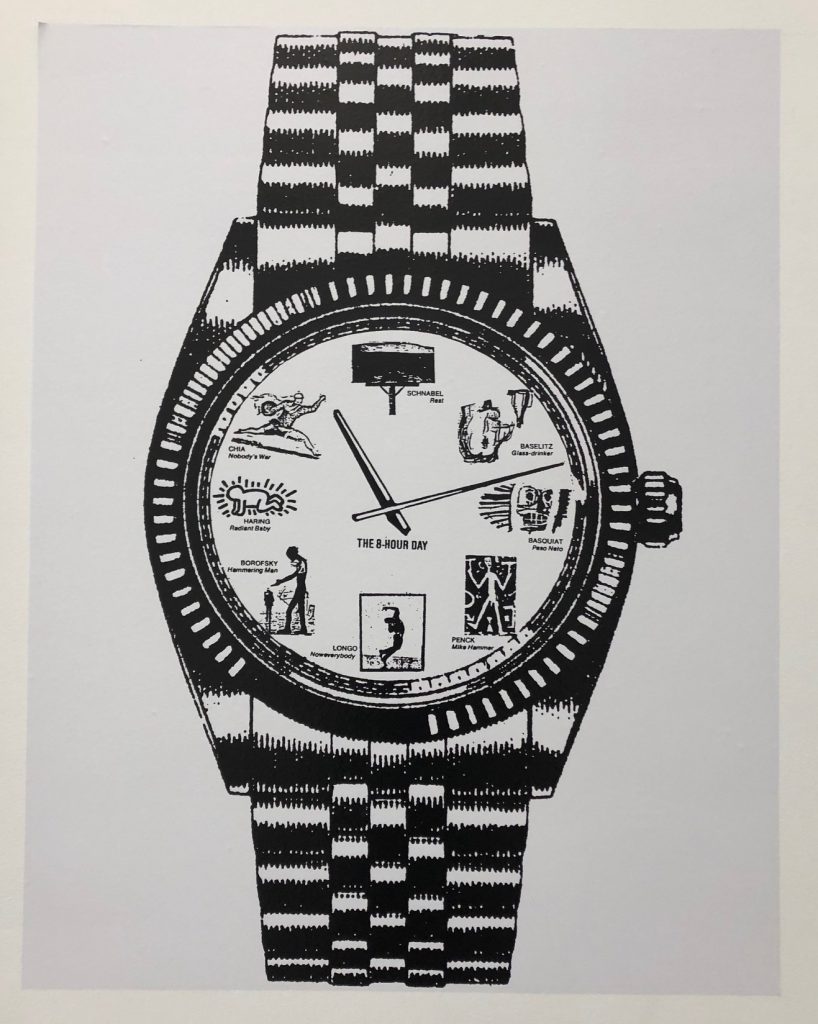

3. Peter Nagy at Jeffrey Deitch

This remarkable exhibition, organized in collaboration with New York gallery Magenta Plains, surveys 1980s artworks by multifaceted art-world figure Peter Nagy. His unusual career includes directing Nature Morte, an influential East Village gallery co-founded by artist Alan Belcher. Now relocated to New Delhi, Nature Morte is today one of the most prominent contemporary art galleries in India. Nagy’s success as an art dealer and curator often overshadows his own achievements as an artist, which is why Entertainment Erases History, an in-depth show of more than 40 major works, is overdue and revelatory.

Adopting a super-graphic, Post-Pop idiom in black-and-white, Nagy explores in his photo-based imagery the mechanics of cultural production. Every work seems like a type of branding strategy or logo design, while centered on themes of information gathering and dissemination. A series of “Cancer Paintings” with abstracted cell-like forms, was instigated by the work of trendy theorists of the 1980s, such as Jean Baudrillard, using cancer as a metaphor for invasive multinational capitalism.

Other works examine city planning and architectural design, with some of the most visually compelling and thought-provoking works echoing the mesmerizing patterning of Islamic architecture. While Nagy’s themes and imagery have a global reach, some of the liveliest and most humorous pieces have a personal or diarist tone, such as The Eight-Hour Day, a watch design for a proposed eight-hour day–the strict and regular workday of a serious. conscientious and ambitious artist, of course. In place of numerals marking the hours are small-scale iconic images by eight of the most prominent and successful artists of the 1980s–Schnabel, Baselitz, Basquiat, Penck, Longo, Borofsky, Haring, and Chia. These are artists whose critical success, at least, Nagy must have envisioned for his own art in response to a wonderful exhibition like Entertainment Erases History.

Carry a Song / Disrupt an Anthem, with, in foreground, The American Dream is Alie and Well, 2012, at Peter Blum Gallery.

4.Nicholas Galanin at Peter Blum Gallery

The works on view in Carry a Song / Disrupt and Anthem, the arresting New York solo debut of Alaska-born artist Nicholas Galanin, address issues of Indigenous people–political aggression against, as well as cultural suppression of Native Americans, specifically. A Tlingit-Unangax artist, with a studio in Sitka, Alaska, Galanin has gained a considerable amount of attention lately for his politically motivated, yet formally elegant works. His large-scale woven cotton and wool tapestry, White Noise, American Prayer Rug (2018), alluding to the racist and xenophobic cacophony that has permeated American airwaves in recent years, was a highlight of last year’s Whitney Biennial and is also featured in the Peter Blum exhibition.

In command of an impressive array of mediums–from painting, sculpture and photography, to installation, video and performance–Galanin achieves a consistent balance of visual beauty and palpable rage against social injustice in practically every work here. Emblematic of the U.S. government’s often hunter-like aggression toward Indigenous people, their land and wildlife, The American Dream is Alie and Well (2012), for example, shows what appears to be a bear rug, but with the American flag insignia instead of fur, and rifle bullets in place of claws. Somewhat more subdued, but no less visually arresting, and harboring a similarly scathing critique, I Think It Goes Like This (Gold), 2019, features a chopped up totem pole, like those of the Pacific Northwest, arranged on the floor, with each section covered in gold leaf. In poetic fashion, it suggests the violent destruction of tribes, their once-glorious Indigenous culture, and the frustrated attempts to reassemble the splintered remains.

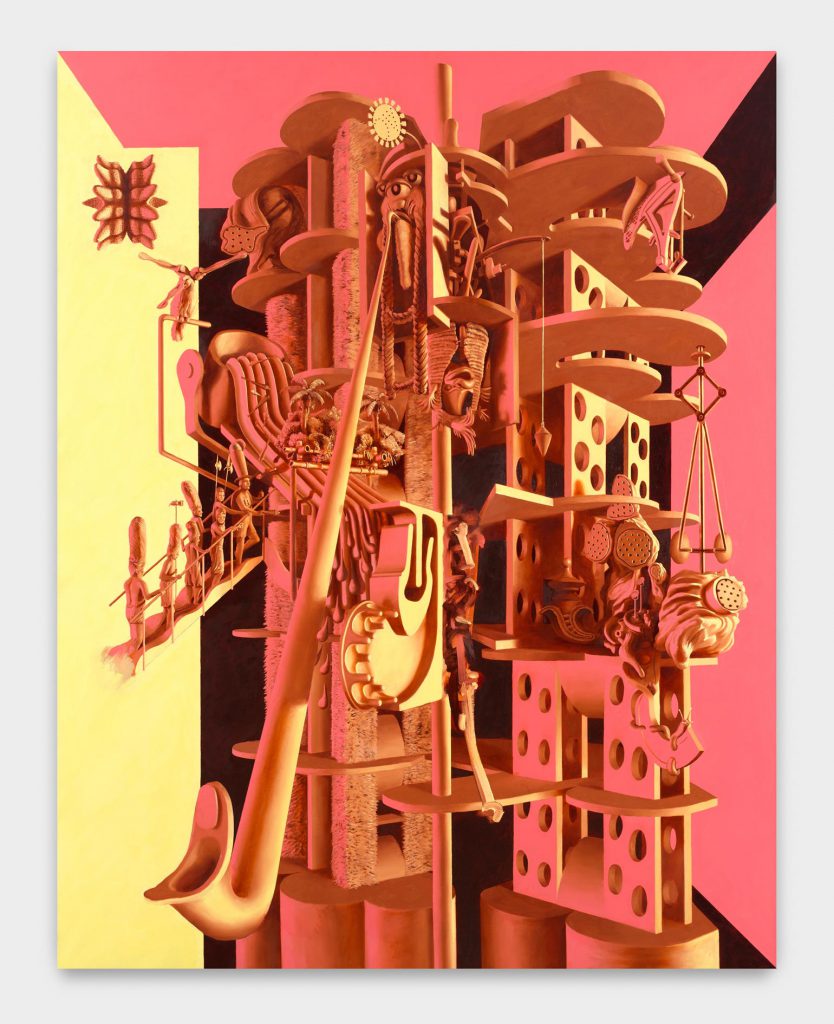

5. Tom Waring at Downs & Ross.

A young artist from Reading, England, Tom Waring (born 1991) already has a devoted cult following, and Consistent Estimator, his stunning New York solo debut, helps to explain why. The images in the ten meticulously wrought oil-on-canvas paintings on view are esoteric and uncanny. The quasi-abstract compositions, with just a hint of Dalí and de Chirico, feature elements that recall bits of industrial equipment, electronic circuitry, weaponry, and fragments of Renaissance and Baroque architecture. With his refined, trompe l’oeil technique, and all the various components compressed within a shallow space, Waring approaches the perfection of an allegorical still-life by William Michael Harnett, such as Violin and Music (1888)

Although the technique may seem a bit archaic, as would the fact that this exhibition was partly inspired by Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century account of the plague that swept Europe, The Decameron–apropos of our time–there is nothing retro about Waring’s work. His foreboding, hallucinatory imagery and acid colors, are unmistakably of the 21st-century. Roba, for example, shows a conglomeration of imaginatively twisted machines or weapons, rendered in myriad shades of blue, set against a blood-red background. Tightly packed into a structure with classical arches, the image suggests a futuristic vision of entropy or military malice.

6. Kenneth V. Young at Edward Tyler Nahem.

This unabashedly gorgeous exhibition focuses on major paintings of the late 1960s and early ’70s by Kenneth Victor Young (1933-2017), whose works are closely associated with the Washington Color School. In each of his lushly romantic abstractions, centralized clusters of soft-edge, colorful orbs glow from within an ethereal space of contrasting hues. In an untitled work from 1974, for example, gold-yellow circular shapes hovering in pools of bright red, appear as fiery orbs shimmering against a cerulean blue sky. In another striking composition on view, Spring Joy (1972), irregular dark black-brown and green orbs bleed into a pale yellow background. All the circular elements seem to writhe and pulsate like living cells seen under a microscope.

In the early 1960s, Young studied physics at the University of Louisville, where he met artists Sam Gilliam, Bob Thompson and others with shared interests in philosophy, politics, jazz and art. Young’s academic pursuits eventually shifted to art; and when he moved to Washington, D.C. after graduating, he landed a job as an exhibition designer for the Smithsonian. There, he gained first-hand knowledge and a greater appreciation of the Smithsonian’s vast holdings of historical works. As scholar and Young biographer Sarah Battle points out in the exhibition catalogue [designed and co-edited by SNAP Editions], the artist was particularity attracted to Renaissance works by Fra Angelico and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Young often explored his African-American heritage in abstract terms. Triptych Miles Davis, (1972), an homage to the jazz maestro, one of the largest (approximately 8 by 12 1/2 feet) and most resplendent work in the show, is a three-panel composition that also alludes to altarpiece triptychs Young studied at the Smithsonian.

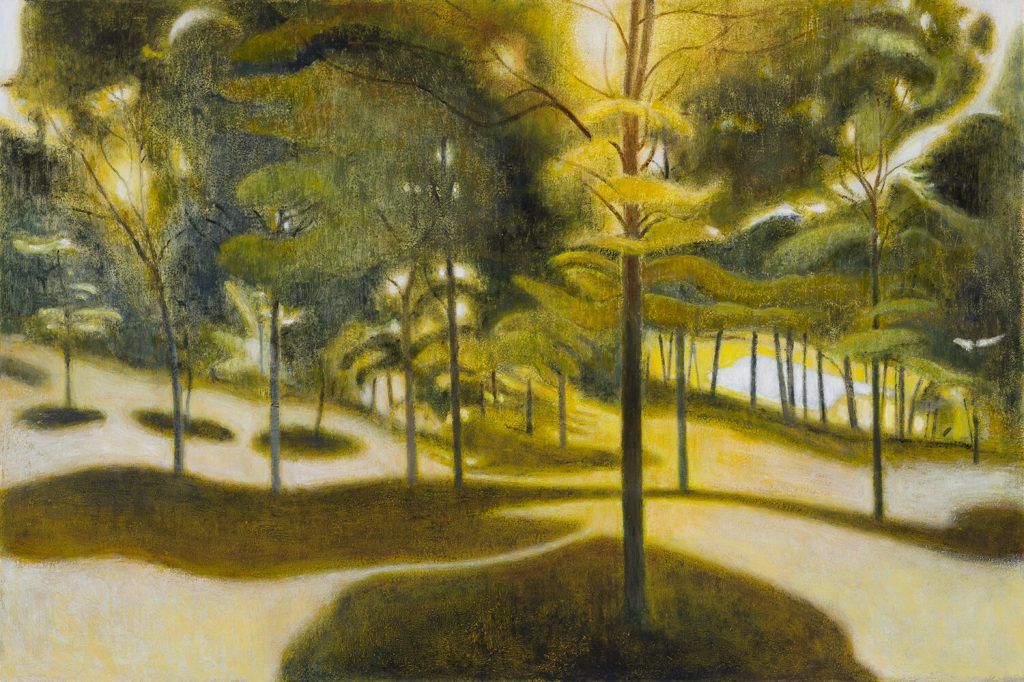

7. Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris Gallery.

While humanity suffers in its struggle with the deadly Coronavirus, other aspects of the Earth’s natural environment, by all accounts, is at present enjoying something of a revival. The recent global shutdown of many factories and other businesses that pollute the planet, not to mention a dramatic reduction of automobile traffic’s toxins, have apparently resulted in cleaner air and water, healthier vegetation, and livelier wildlife. From this perspective, Ron Milewicz’s recent paintings of radiant landscapes of glistening fields, trees and wild shrubs, seem at once prescient, timely and timeless, suggesting an urgent homage to Nature.

Known for his refined and imaginative cityscapes, Milewicz in recent years has spent part of his time in rural upstate New York. There, he is able to connect surrounding nature to an interior vision with a similarly heightened imagination–in terms of expressive line, color and composition–evident in his urban scenes. This exhibition’s title, Axis Mundi, refers to the earth’s axis, or the symbolic place where heaven and earth meet. The small scale of these oil paintings can hardly contain Milewicz’s cosmic vision.

Down the Meadow shows an undulating field punctuated with rows of sinewy trees and bushes. Aglow with an ethereal incandescence, the image recalls one of Charles Burchfield’s hallucinatory watercolors. Milewicz’s vision, however, seems to me even more arcane, and corresponds on some level to the work of 19th-century British Romantics like Samuel Palmer, whose images, such as the hushed landscape of The Herdsman’s Cottage, or Sunset (1850), convey a powerful sense of awe and wonder in nature’s presence. Similarly transcendent, Milewicz’s nocturnal landscape, Pink Moon, shows a tree with bare limbs gracefully stretching heavenward, intertwined with a network of intensely glowing moonbeams.

Brian Rutenberg, A Little Long Time, 2019, at Forum Gallery.

8. Brian Rutenberg at Forum Gallery.

South Carolina-based artist Brian Rutenberg has for some years developed and refined a unique landscape vision that is made of equal parts lyrical, gestural abstraction, and convincing, empirical realism. Rutenberg has proven to be a consummate colorist, undeterred by incongruous analogous or deliberately clashing hues, as well as a textural adventurer, favoring piled on layers of pigment that lend a shimmering fluid and luminous surface quality to each work. The Pond, a radiant exhibition of recent large-scale paintings, centers on a water theme, which the artist has returned to periodically throughout his career.

Spanning the central area of A Little Long Time, a striking horizontal composition (48 by 90 inches), an elongated oval in shades of deep red, appears to represent a forest pond or a lake seen at sunset. Dynamically traversing the oval at slight diagonals, thick, sumptuous brushstrokes in vivid purple, ostensibly indicate shadowy tree trunks. For the artist, born in Myrtle Beach, water has long been a central to his art. For the recent series, he credits Hudson River School artists, such as John Frederick Kensett, as major inspirations. Several brilliant works by Rutenberg in this show, including Clamdigger, explore the reflective–and mystical–properties of water. Here, an aurora of pink-gold near the top of the canvas shines upon a glassy pool of water in the lower portion, rendered with patches of aqua blue, pink, and deep red. An attribute of Rutenberg’s best works, this painting combines visual excitement with meditative quietude.

9. Allison Schulnik at P.P.O.W.

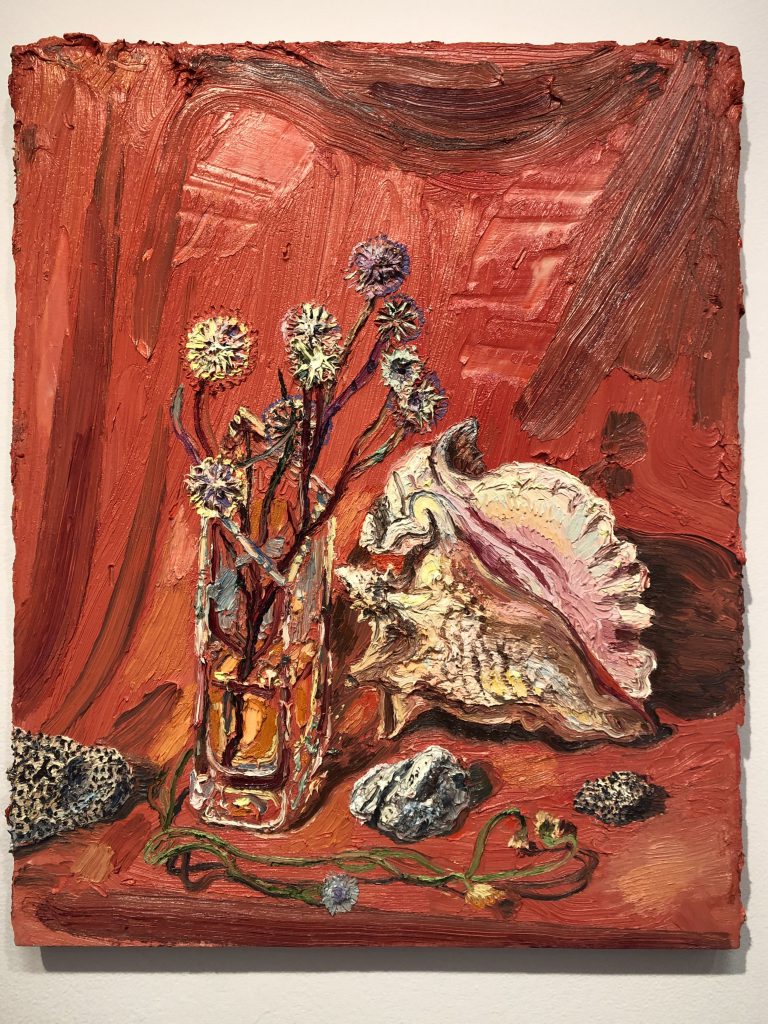

Painter and filmmaker Allison Schulnik lives and works in a remote Southern California desert. She paints what she sees around her—the subtle shifts in light and color, and the ever-evolving flora and fauna that share her environs are central to her art. She also recently gave birth to a daughter, who appears in a number of works. On view in Hatch are twenty-seven paintings, plus one video animation (Moth, 2019) running continuously in a rear gallery. The works are generally small or medium-size, though each one exudes a hyper-focused energy and intensity.

Particularity striking are Schulnik’s small paintings of objects and animals. I doubt that an insect has ever been depicted as appealingly as her Tarantula, with inches thick paint rendering the creature’s furry gray body ensconced in icing-like layers of pink pigment. Desert Pincuhsion #2 has the dignity and grace of a Chardin still-life, an arrangements of sea shells, coral, rocks and flowers that clearly have personal resonance, but can be universally understood.

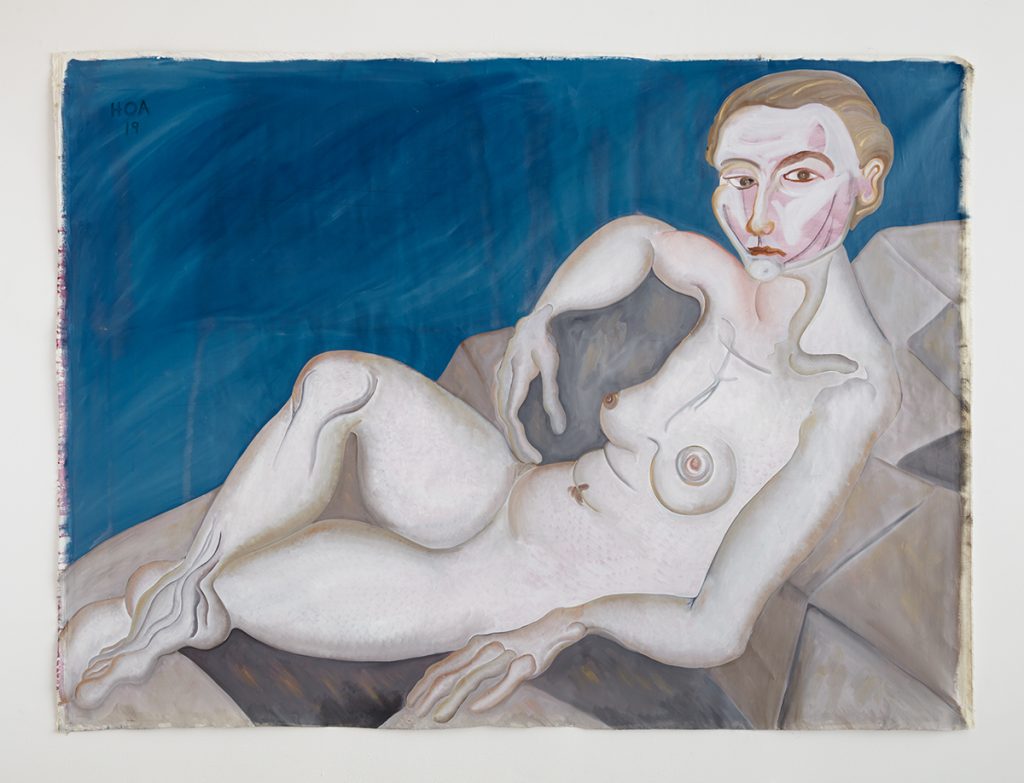

10. Helen Oliver Adelson at Howl! Arts.

Helen Oliver Edelson engages in a specialized kind of portraiture with stylistic antecedents in Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) German painting of the Weimar Republic of the 1920s and early ’30s. Her paintings could compare favorably with expressionist portraits by Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, Christian Schad, and others in their raw, psycho-sexual inferences. Unlike those artists, however, Edelson does not aim toward satirical comment or social critique regarding her subjects. Instead, she endeavors to reveal the sitter’s inner life, plus the unique relationship of each individual to his or her body, as well as the fundamental–and profound–sense of being in the world.

Her favorite subjects are family and friends–her brother, the renown writer and performance artist Edgar Oliver, is a patient and recurring model–Penny Arcade, and other downtown and underground New York artists are also major protagonists here. This exhibition, The Road, features large-scale portraits that explore the artist’s own psychological states as much as her subjects’. The angst she exudes in her work stems largely from childhood experiences. As writer Tom Breidenbach observes in the exhibition’s catalogue, to which I also contributed an essay, “The isolation of childhood appears to inform the gaze Oliver [Adleson] casts on the world.”

Part of Adelson’s worldview and imagery reflects her current environs, the town of Tarquinia, Italy, where she now lives and works for much of the year. Famous for its Etruscan tombs and the paintings therein, plus its extraordinary National Etruscan Museum, Tarquinia, its city streets, and surrounding hillsides are also major subjects of Adelson’s art. The ancient town’s haunted past, its mood and tone, may be felt in her portraits as well as in her cityscapes. ●

Along with SNAP Editions editor Sarah S. King, president George G. King, and the entire SNAP Editions team, I would like to dedicate this column to the memory of our friend and colleague Maurice Berger, the brilliant writer and curator who succumbed to complications of Covid-19 on March 22.

Text ©David Ebony 2020

If i may, i want to say that i loved the choice of subject wow how interesting congratulations for the amazing content very well written text.

Your website is amazing congratulations, visit mine too:

https://b9g.net

.